- ©

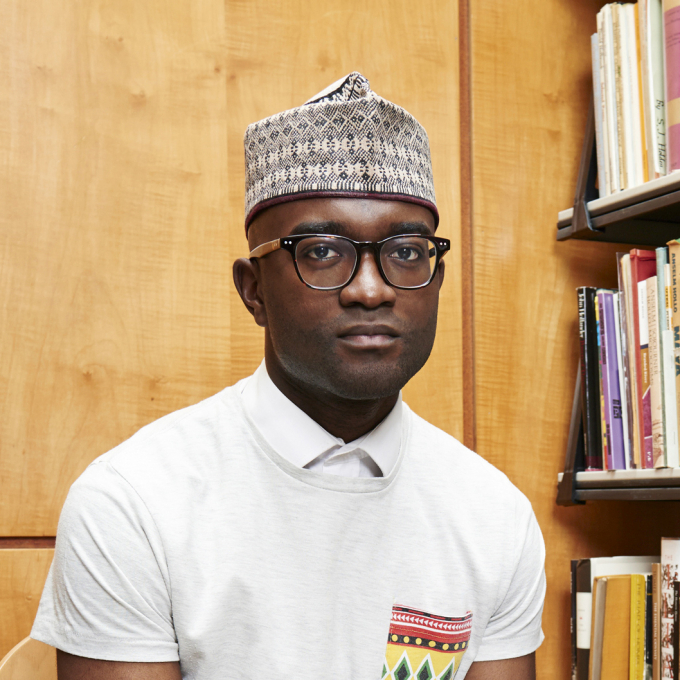

- Oliver Holms

Inua Ellams

- Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

Biography

Inua Ellams was born in Nigeria in 1984 and moved to the UK as a child.

He is a poet, performer, playwright, graphic artist and designer. He started performing in cafes in 2003 and has since worked in venues which include Queen Elizabeth Hall, Tate Britain, Theatre Royal Stratford and Glastonbury Festival. He has also undertaken several commissions, including those for Tate Modern, Soho Theatre and for the BBC's Politics Show.

His first book was the best-selling poetry pamphlet, Thirteen Fairy Negro Tales (2005), and in 2009 his debut play, The 14th Tale (2009), a partly autobiographical coming of age tale, won a Fringe First Award at Edinburgh Festival, toured, and ran at the National Theatre in 2010. His second play, Untitled (2010), toured in Autumn 2010.

His creative work has been recognised with a number of awards, most recently, The Live Canon International Poetry Prize, an Arts Council of England Award, a Wellcome Trust Award, shortlisted for the Brunel Prize for African Poetry, longlisted for the Alfred Fagan Award, and a 2009 Edinburgh Fringe First.

He has been commissioned by the Tate Modern, Louis Vuitton, Chris Ofili, National Theatre, BBC Radio & Television, Battersea Arts Centre and Soho Theatre. His first two books of poetry Thirteen Fairy Negro Tales (2005) and Candy Coated Unicorn and Converse (2011) are available from Flipped Eye, and several plays including Black T-shirt Collection (2012), Knight Watch (2012) and Cape (2013) are available from Oberon. In 2005, he founded the Midnight Run, a cross art form nocturnal urban movement to reconnect inner city lives with inner city spaces.

His critically-acclaimed play Barber Shop Chronicles debuted at the National Theatre in 2017. Inua Ellams lives and works in London.

Critical perspective

Inua Ellams is a multi-disciplinary artist, working as a poet, a playwright, a performer, and a graphic artist. He is one of the bright new stars of the British stage, his critically-acclaimed play Barber Shop Chronicles having returned to the National Theatre in late 2017 after a sell-out run earlier the same year. He also runs a R.A.P. Party for poets to read work inspired by any aspect of hip-hop culture and he tweets about all this and more.

‘He captures our attention as soon as he opens his mouth,’ enthused The Times in appreciation of Inua Ellams’s performance of 14th Tale, in 2009. It was Ellams’s debut play, a short semi-autobiographical solo performance, without costume change or props, using poetic language to create a hilarious bildungsroman about a trouble maker and his relationship with his father. At this early stage of his career, Inua Ellams, already adept at using his personal experiences to tell global stories, was exploring the lineage of troublesome men in his family. He was the only boy. His father had suffered a stroke. Unsurprisingly then, 14th Tale opened in a hospital where the young man had just learnt this news. The play coughed up ‘a nervous kid with bloody trousers, geeky glasses and an impish grin.’ He told his coming of age story using flashbacks, taking the audience from birth and early childhood, through boarding school in Nigeria and the family migrating to London when the hero is 12, then Dublin where he was ‘the only black boy in school,’ first girlfriends, and on to the father-son relationship, leading up to father’s death. The writing was clever and sly. As a performer, Ellams engaged his audience with catlike movement. Speaking in different accents, adapting to different situations and countries, 14th Tale showcased two of the indelible qualities with which his later work shone.

Ellams began by performing long poems by himself and progressed to longer poems to be performed by others before turning to work for larger casts. ‘I write these dense poems, try to pack them with imagery to always keep a mind turning and listening. This means that my work thrives in quiet and in sobriety.’ Sometime in 2007, he grew tired of presenting work of the latter description to ‘audiences intoxicated or in an environment of easy distraction.’ For this reason, he preferred to work in solitary confinement, in a blank space where light and sound could be controlled. Theatre gives exactly that opportunity.’

As Michael Pearce has elaborated more broadly in his analysis of ‘Black British Drama – A Transnational Story’, the black performance poetry tradition to which Inua Ellams belongs, challenges white hegemonic power by centralising the black body and its attendant signifiers of blackness – hair, for instance – and focuses on themes of power and empowerment. Pearce typifies Ellams’s work as a ‘Multiple Personality Diasporic Disorder.’ Literary comparisons can also be made with the work of older Jamaican, UK-based poets Linton Kwesi Johnson and Jean ‘Binta’ Breeze whose provocative writings about racism and on the theme of un(belonging) set alive the dub poetry scene of the 1970s onwards.

Among the key influences in Inua Ellams’s work though, is African orature, the oral tradition of the continent. He has felt himself influenced by other Nigerian writers, Chinua Achebe and Ben Okri, both well-versed in Nigerian myth and folk tales; and his voice is interestingly shaped and transmuted by his transnational journey and residence in the United Kingdom which has offered up a ragbag of high and low forms, the whimsy of Salman Rushdie and Neil Gaiman, the playfulness of Terry Pratchett, the powerful beauty and delicacy of Shakespeare’s Hamlet with his favourite line being Guildenstern’s: ‘the very substance of the ambitious is merely the shadow of a dream.’

Ellams dreams big. His big themes are masculinity, especially black masculinity, identity, belonging, displacement and destiny; displacement from a religious or spiritual point of view, and displacement from his immigrant background. The predicaments facing the characters in his second play Untitled, another solo performance that blends African storytelling with traditional theatre, are questions of birth, family and community. In this magic realist fictional story two brothers are separated at birth. The titled child is seized by the mother, leaving the nameless one to suffer a chaotic and blasphemous existence. Through it, the playwright asks us to consider who were really are and how our sense of self is retained and defended in changing environments. Black T-shirt Collection, his third play, also features separated brothers, this time involving Nigerian foster brothers Matthew and Mohammed for whom global success with a t-shirt brand comes tainted with blood. Artistic Matthew is a Christian boy adopted by a Muslim family, and by the time they are teenagers they are brothers in all but blood such is their ‘fight-formed, dust-ridden trust.’ Theirs is a journey criss-crossing the globe and including the bazaars of Cairo and the factories of China. The Guardian critic Lyn Gardner appreciated the easy intimacy of the work which, ‘alights like an elegant butterfly on a great many issues, including homophobia, sectarianism and the demands of capital.’

Several critics have admired Ellams’s linguistic, but low-key virtuosity; Gardner liked ‘the words falling skittishly over each other,’ many praise the wit and inventiveness of his speeches. When he stands before audiences - African, European and increasingly global audiences - Inua animates the themes of his personal odyssey - being born in Nigeria and migrating to England at the age of 12 – he describes what it means to be stateless, paperless and in limbo; he puts black masculinity under the microscope, storytelling with humour as in An Evening With an Immigrant (2017).

Inspired by the true story of a Leeds barber, Ellams' latest play, Barber Shop Chronicles, takes an African diasporic tour of six cities – London, Harare, Lagos, Accra, Johannesburg and Kampala, Uganda; – where each urban barber shop thrums with the stories of African men: sages, role models and father figures who keep the men together. Their chronicles include ‘confessionals, politics, feuding, tales of men away from their homes, men cut off from their fathers, men in search of companionship,’ wrote the Guardian’s Susannah Clapp, one of the many critics who have applauded the play. By the cast of 12 black men, the audience are treated to an energetic exploration of contemporary African masculinity, jokes, the high tension surrounding a big Barcelona-Chelsea match, soft thoughts on love, friendship, the ties that bind men, world and local politics, religion, race, history and memory. Representative of Ellam’s work, it is global, high and low, gilded, black, and male.

Delia Jarrett-Macauley, 2018