What does winning the Nobel Prize for Literature do to a writer? Always, it changes his or her work in the eyes of readers. Some of the politically inspired or perverse or downright odd decisions of Swedish Academy over the years may have nourished scepticism about the status of the winner, but the annual announcement confers unrivalled prestige. If the award goes to a writer we have read, it asks us to see how his or her work reaches beyond passing literary fashion. The Man Booker Prize recognizes this year’s thing; the Nobel Prize, awarded to an oeuvre rather than a single book, claims to identify literary merit sub specie aeternitatis.

The prize was set up to reward what, in its English translation, is described as ‘the most outstanding work in an ideal direction’ (in Swedish, en idealisk riktning). The words come from Alfred Nobel’s will. They might refer to literature that is idealistic in intent, but also mean literature that, in the case of novels or plays, universalises its characters, removing them from particular times and places.

Playwrights like Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, novelists like Albert Camus and William Golding, have seemed peculiarly to fit the bill. The citation for Golding, who won in 1983, celebrated his fiction for having ‘the universality of myth’, and for illuminating ‘the human condition in the world today’. Schoolboys on an island somewhere, a group of the last Neanderthals, men and women on a ship bound for Australia: Golding creates situations removed from his own present day so that he can anatomise human appetites and the dark human talent for predation.

Except in those cases (there have been eight) where the Nobel Prize for Literature goes to a Swedish writer, the eighteen members of the Swedish Academy who make the annual decision are judging work that is not written in their first language. Sometimes academicians will have read the work only in translation. (As all will be competent in English, Anglophone writers are at an advantage.) What are the qualities that reach beyond the nuances of an intimately known tongue? It is striking that three of the last five British winners of the prize have been immigrants: V.S. Naipaul, Doris Lessing, and Kazuo Ishiguro, who came to England when he was six years old. Perhaps such authors have been schooled by experience to think beyond nationality.

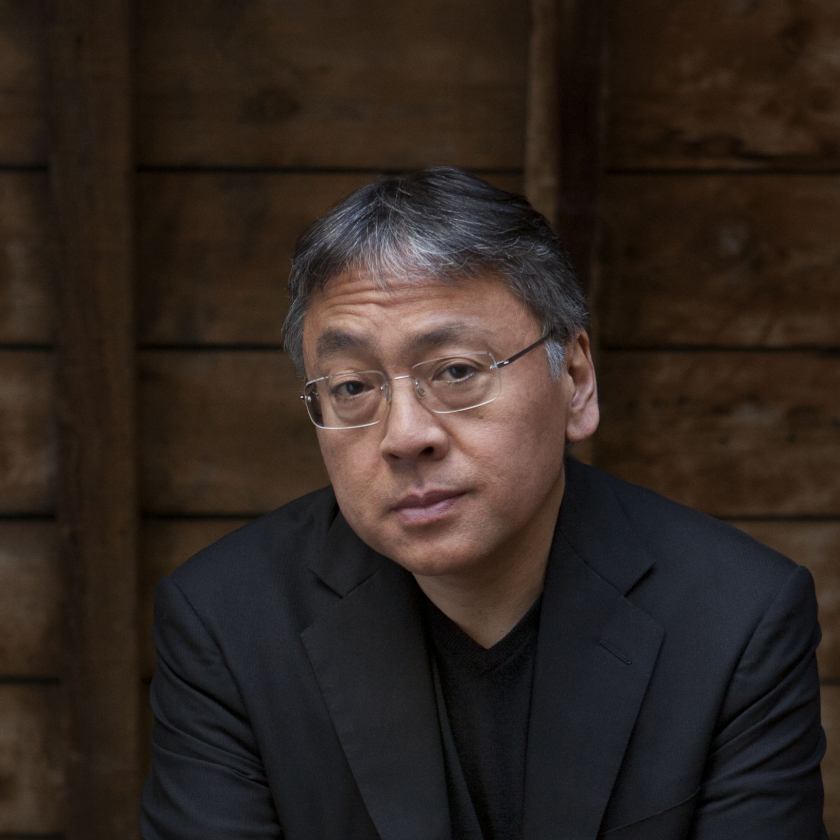

When Ishiguro was awarded the Nobel Prize this year there was initial surprise because he had not appeared on the lists of likely winners – but then a widespread sense of the justice, even the rightness, of the decision. It is not that any consensus has declared him the leading British novelist, somehow ‘better’ than Mantel or McEwan or Rushdie. Rather, his fiction achieves a universality that is as much an achievement of style as a question of subject matter. Ishiguro’s novels abstract their characters from any period or known society.

Some seem to take place in Britain, but Ishiguro’s fiction always makes a familiar place strange. The narrator of A Pale View of Hills, his first novel, is Japanese, but lives in England, and, though now a widow, has had a British husband. From her comfortable, alien adopted country she looks back to her earlier life in Nagasaki, where Ishiguro himself was born. She is estranged from both places. The Remains of the Day takes us to the English shires and to that most literary location, the English country house. Yet Ishiguro makes this a place of misconstrued etiquette and baffled communication. Never Let Me Go radically skews the supposedly civilized values of a peculiar British institution: the progressive boarding school. It makes English provincial towns places of mystery and foreboding, while the English countryside, through which the protagonist travels on her unquestioned missions, is weirdly emptied of people. In his most recent novel, The Buried Giant, we are taken back to an ancient Britain where the capacity of the leading characters to remember where they have been, or who they have known, seems to be crumbling.

The Swedish Academy’s citation describes Ishiguro as a writer ‘who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world’. It sounds not unlike the citation for a previous British winner, Harold Pinter, ‘who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression’s closed rooms’. There is unintended comedy in the solemnity of these pronouncements, but there is also something true. Like Pinter, Ishiguro discovers the pressure of unstated emotion in language that is restricted or even impaired. The narrators of The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go grasp at clichés. The nightmarish world of The Unconsoled is rendered in English where precision shades into pedantry, and characters stave off terror with platitude. The five different narrators of the connected stories that make up Nocturnes are painfully, or laughably, unperceptive, their musical articulacy a kind of compensation for the limitations of their sentences. For any reader in any place, the powerfully, disconcertingly simplified language of this fiction is readily translatable, utterly strange yet common to us all.

The Nobel Prize in Literature will be presented to Kazuo Ishiguro in Stockholm on December 10th 2017.