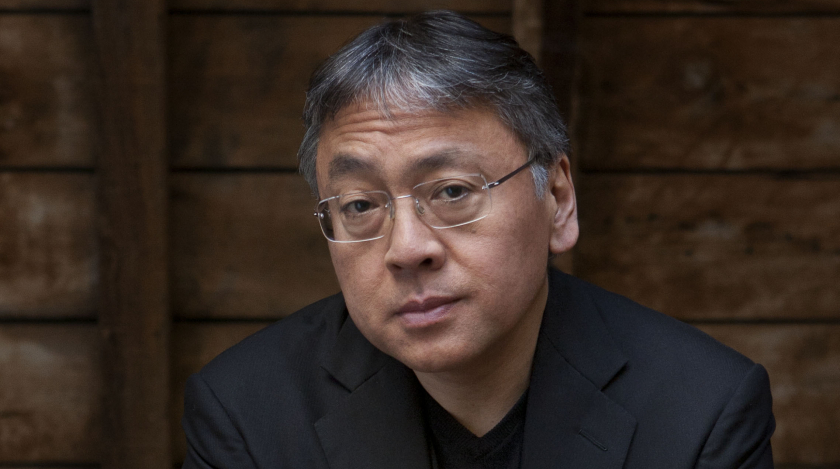

- ©

- Jeff Cottenden

Kazuo Ishiguro

- Nagasaki, Japan

Biography

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki, Japan, on 8 November 1954. He came to Britain in 1960 when his father began research at the National Institute of Oceanography, and was educated at a grammar school for boys in Surrey.

Afterwards he worked as a grouse-beater for the Queen Mother at Balmoral before enrolling at the University of Kent, Canterbury, where he read English and Philosophy. He was also employed as a community worker in Glasgow (1976), and after graduating worked as a residential social worker in London.

He studied Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia, a member of the postgraduate course run by Malcolm Bradbury, where he met Angela Carter, who became an early mentor. He has been writing full-time since 1982. In 1983, shortly after the publication of his first novel, Kazuo Ishiguro was nominated by Granta magazine as one of the 20 'Best of Young British Writers'. He was also included in the same promotion when it was repeated in 1993.

In 1981 three of his short stories were published in Introductions 7: Stories by New Writers. His first novel, A Pale View of Hills (1982), narrated by a Japanese widow living in England, draws on the destruction and rehabilitation of Nagasaki. It was awarded the Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize. It was followed by An Artist of the Floating World (1986), which explores Japanese national attitudes to the Second World War through the story of former artist Masuji Ono, haunted by his military past. It won the Whitbread Book of the Year award and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction. Ishiguro's third novel, The Remains of the Day (1989), is set in post-war England, and tells the story of an elderly English butler confronting disillusionment as he recalls a life spent in service, memories viewed against a backdrop of war and the rise of Fascism. It was awarded the Booker Prize for Fiction, and was subsequently made into an award-winning film starring Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson. His next novel, The Unconsoled (1995), a formally inventive narrative in which a concert pianist struggles to fulfil a schedule of rehearsals and performances in an unnamed European city, was awarded the Cheltenham Prize in 1995. Kazuo Ishiguro's fifth novel, When We Were Orphans (2000), is set in Shanghai in the early part of the twentieth century, and is narrated by a private detective investigating his parents' disappearance in the city some 20 years earlier. It was shortlisted for both the Whitbread Novel Award and the Booker Prize for Fiction. His sixth novel is Never Let Me Go (2005) and he collaborated with George Toles and Guy Maddin on the screenplay for The Saddest Music in the World, a melodrama set in the 1930s, starring Isabella Rossellini. In 2009, his first short story collection, Noctures: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall, was published, and shortlisted for the 2010 James Tait Back Memorial Prize (for fiction). His latest novel The Buried Giant was published in 2015.

He has also written two original screenplays for Channel 4 Television, A Profile of Arthur J. Mason, broadcast in 1984, and The Gourmet, broadcast in 1986. He was awarded the OBE in 1995 for services to literature and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He was awarded the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 1998. His work has been translated into over 30 languages. In 2017 he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Kazuo Ishiguro lives in London with his wife and daughter.

Critical perspective

Ishiguro's novels are preoccupied by memories, their potential to digress and distort, to forget and to silence, and, above all, to haunt.

When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2017, the Swedish Academy praised Ishiguro’s work for unearthing ‘the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.’ If Ishiguro's novels tend to defy genre expectations, with each new work veering from the conventions of the last, what haunts all of them is the abyss of memory and its potential to shape and distort, to forget and to silence. His protagonists seek to overcome the chasms and absences left by loved ones and lost family members by making sense of the past through acts of remembrance.

His first two novels, A Pale View of Hills (1982) and An Artist of the Floating World (1986), take the reader on compelling journeys into the minds and memories of their Japanese protagonists. Private recollections share complex relationships with wider historical events shaking the world. A Pale View of Hills and An Artist of the Floating World are set respectively in the aftermath of the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. These traumatic events structure and scar the two narratives, which are skilfully composed around strategic silences and repressions. They are psychological portraits of how characters cope with traumatic events.

Ishiguro's characters are pathologically unreliable. They tend to deceive, rather than reveal themselves, through storytelling. His novels are not attempts to render the past convincingly, but rather to pursue how individuals interpret and (re)construct their lives through history. For example, A Pale View of Hills is narrated by Etsuko who is living in England. Her memories of the past and of her dead daughter Keiko (who committed suicide in Manchester) have been stirred by the arrival in England of her second child, Niki. While Etsuko's tale seems keener to discuss her old friendship with Sachiko and her daughter Mariko in Japan, the novel also implies that Etsuko, Sachiko, Mariko and Keiko are the same person. To what extent Etsuko is concealing or revealing the past through her recollections is ultimately left to the reader to decide.

A similar story emerges in An Artist of the Floating World. Ono is also haunted by the past. His wife is dead following a bombing raid that destroyed large sections of their house. His son dies fighting the Chinese. Ono does not dwell explicitly on these personal losses, and like Etsuko he seems oddly detached from them. However, as he strolls through the shattered remains of his home he also circles around this past, which appears to the reader obliquely, through glimpses and side-glances.

As the powerful physical and psychological detail of An Artist of the Floating World suggests, Ishiguro's work is often preoccupied with interiors: not simply with journeys into the mind and memory, but also with the domestic indoors. It is upon private rather than public terrain that Ishiguro's work feels most at home, from the powerful image of Ono's broken house in Japan, to the faded grandeur of the quintessentially 'English' Darlington Hall in The Remains of the Day.

At the same time the protagonists of these texts are all radioactive with the fallout of the momentous events that are both central and peripheral to their narratives. In The Remains of the Day we are offered the narrative of Stevens, a butler. The privileged, isolated world of Darlington Hall reveals a society seemingly detached from national and international affairs. Yet it gradually becomes clear that the late Lord Darlington was himself a Nazi sympathiser during the war, a fact that Stevens struggles throughout the text to reconcile with his own view of his employer as a great man. It is 1956 and Darlington Hall has a new master, an American businessman who encourages Stevens to take some time off. As he travels by motor car to visit former housekeeper, Miss Kenton, Stevens' memories unfold in the form of a travelogue. Yet, as with Etsuko and Ono's narratives, Stevens' flashbacks help us to make sense of his past and simultaneously expose that past as provisional, partial and unreliable. As the story progresses, we learn that Stevens helped his master entertain Fascist leaders like Mosley and that his visit to Miss Kenton (a former lover) has an ulterior motive. Stevens is a deluded character, and as such readers sympathise with, but cannot quite place faith in him. The stunning precision and clarity of Ishiguro's prose in The Remains of the Day belies the fact that it is also a fiction about imprecision and the distortions of language.

As the novelist Salman Rushdie has noted:

‘Now that the popularity of another television series, Downton Abbey, has introduced a new generation to the bizarreries of the English class system, Ishiguro's powerful, understated entry into that lost time to make, as he says, a portrait of a "wasted life" provides a salutary, disenchanted counterpoint to the less sceptical methods of Julian Fellowes's TV drama. The Remains of the Day, in its quiet, almost stealthy way, demolishes the value system of the whole upstairs-downstairs world.’

After the critical acclaim of the Booker Prize winning The Remains of the Day, Ishiguro's next novel represents a change of tack. If the characters of the first three novels could be said to be 'looking back and ordering ... experience' then Ishiguro has noted that Ryder of The Unconsoled (1995) is 'someone in the midst of chaos'. The narrative unfolds within an unspecified European city and there is a dislocated, dreamlike quality to Ryder's narrative. If the protagonists of Ishiguro's earlier novels supplied memory with an imaginary coherence, a unifying order, then this novel abandons the idea of a stable identity as the text shifts, unexpectedly and incoherently, between different accounts of Ryder's existence. The epistemological questions raised by the first three novels become ontological questions in The Unconsoled; a deft, disorientating text that reveals the novelist's commitment to narrative innovation and experiment.

Silencing those critics who found the ambition and abstraction of The Unconsoled difficult to swallow, Ishiguro's next novel represents a return to realism and the prevailing theme of memory. When We Were Orphans (2000) is set in the 1930s and follows the story of London-based detective, Christopher Banks. Returning to Shanghai in an attempt to solve the mystery of his missing parents who disappeared when he was ten, the novel takes us on a journey into personal memory and the past through its imaginative deployment of the detective genre. Ishiguro parodies the speech patterns of classic detective fiction only to suggest that the act of detection is more elusive than it first appears.

Never Let Me Go (2005) takes its name from a fictional pop song to which the protagonist, Kathy H., dances during her days at the mysterious boarding school of Hailsham. The youthful, innocent Kathy imagines the lyric as a mother calling out to her child, and she is often to be found swaying to the words while embracing a pillow. What detaches the words and actions from cliché is the woman who looks on at Kathy, the mysterious figure known simply as Madame, who is reduced to tears by the scene. Much later in the novel we discover why. Hailsham is an experimental school for clones reared to provide organs for human transplantation. Madame explains to Kathy later in life that the reason she cried is because the dancing girl appeared to her to be asking an older, more humane world not to let her go. Shortlisted for the 2005 Man Booker Prize for Fiction and other prestigious literary awards, the novel has been translated into more than a dozen languages and was adapted into an award-winning film starring Keira Knightley in 2010.

Ishiguro’s more recent work, Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall (2009), is a poetic short story cycle, and an unexpected break with the novel form. But arguably Nocturnes is more a return to form than a departure: the author’s earliest published work consisted of short stories (‘A Strange and Sometimes Sadness’, ‘Waiting for J’ ‘Getting Poisoned’ (1981) and ‘A Family Supper’ (1982)), many of which are collected in Introduction 7: Stories by New Writers (1981). The stories of Nocturnes move from tourist Venice, to the Malvern Hills, from London to Hollywood. Connecting all of them, as the title suggests, is music and dusk. The stories are populated by cellists, guitarists, saxophonists, and crooners in a carefully orchestrated narrative that is itself a sort of quintet.

After the verbal economy of Nocturnes, The Buried Giant (2015) represents Ishiguro’s biggest book to date, and his most extended meditation on the vicissitudes of memory. The book combines something of the epic vision of J.R.R. Tolkien with the restless quest-filled world of Arthurian legend, but the prose and tone of the novel also manages to feel uniquely original.

The Buried Giant follows the story of Axl and Beatrice as they set forth from their hobbit-like burrow on a journey across the treacherous, ogre strewn landscapes of sixth century Britain in search of their son. It is what Ishiguro has called 'the eve of England', when a fragile truce exists between the newly arrived Saxon and the Britons, thanks largely to a collective amnesia that has settled over the islands inhabitants, like the mist that rolls perpetually over the countryside.

The emphasis on personal memories in Ishiguro’s earlier books seems to expand in The Buried Giant to become part of a state-of-the-nation dilemma hinting at an opaque allegory for our own dark times. Yet the focus and power of this story is the love shared by Axl and Beatrice. The tragedy behind the elderly couple’s story is that they can only barely remember the existence of their own son. Axl consoles his wife at one point: ‘Our memories aren’t gone for ever, just mislaid somewhere on account of this wretched mist. We’ll find them again, one by one if we have to. Isn’t that why we’re on this journey?’

A little later their condition is described as a ‘strange affliction’. Beatrice, meanwhile refers to forgetting as like ‘a sickness [that has] come over us all’. But remembering, the unearthing of buried pasts, does not necessarily emerge as a remedy in The Buried Giant. Axl and Beatrice’s unconditional love for one another is partly sustained by amnesia, as is the precarious peace that exists in Britain. With his seventh novel, Ishiguro offers no solutions to the protracted predicament of memory explored in his earlier work. Yet in the still clarity of this novel’s dazzling close, we encounter something at once moving and unforgettable. As the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature committee noted, Ishiguro ‘is someone who is very interested in understanding the past, but he is not a Proustian writer, he is not out to redeem the past, he is exploring what you have to forget in order to survive in the first place as an individual or as a society’.

James D. Procter (2017)

Bibliography

Awards

Author statement

'I am a writer who wishes to write international novels. What is an 'international' novel? I believe it to be one, quite simply, that contains a vision of life that is of importance to people of varied backgrounds around the world. It may concern characters who jet across continents, but may just as easily be set firmly in one small locality.'