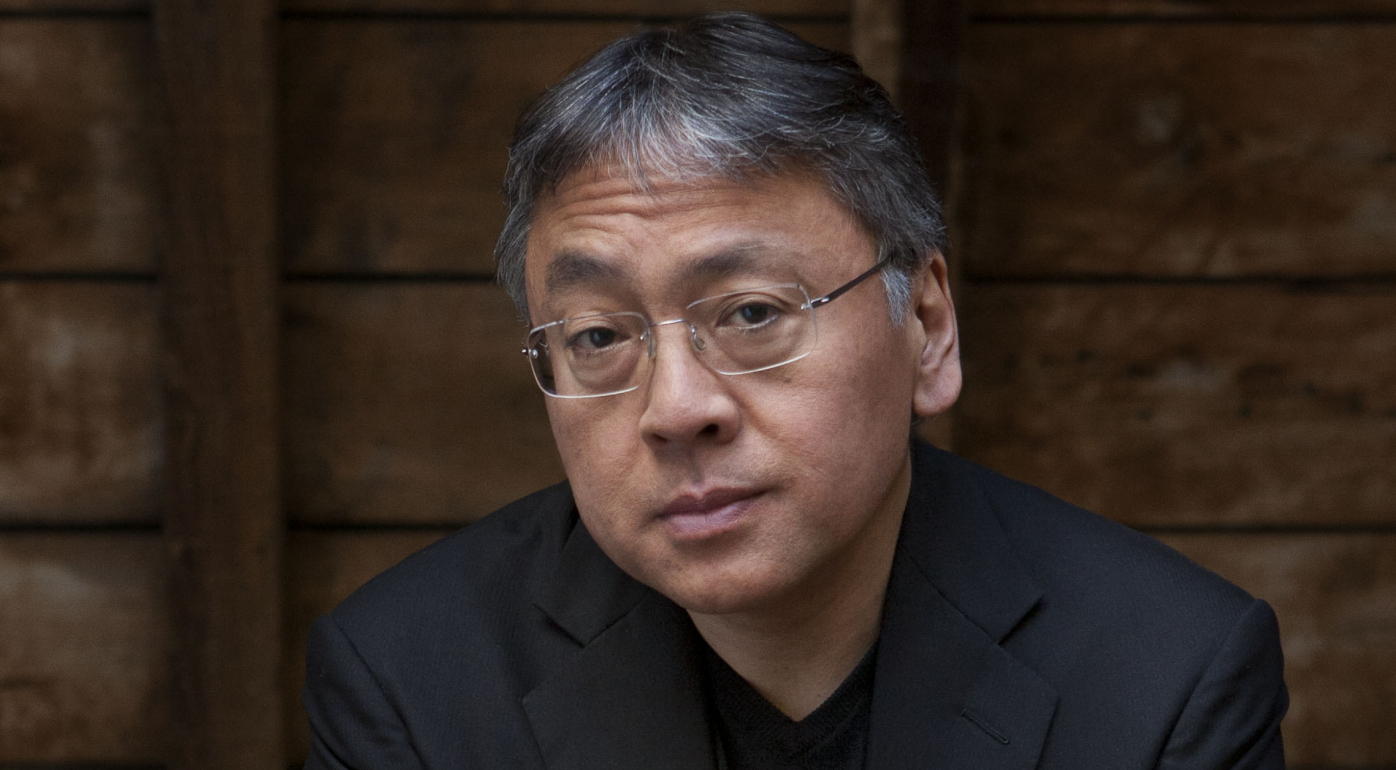

Earlier this month, British author Kazuo Ishiguro – winner of the Booker Prize in 1989, and shortlisted in 1986, 2000 and 2005 – collected the Nobel Prize for Literature at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm. In his lecture at the ceremony, he told of the times in his life in which he made his writing breakthroughs: small, private moments when he was at home listening to music, reading in bed, or watching films, and thinking about the ways that these various works of art achieved their effects.

He mentioned, for example, his time at University of East Anglia in his twenties, when he began to create a fictional Japan structured around his own personal memories and perceptions, rather than attempting to document the place; the day he was inspired to develop the relationships between his characters, allowing the plot to take care of itself, in Never Let Me Go; and the many years between the initial desire to dramatise a nationwide “forgetting”, an idea which permeates The Buried Giant, and the writing of the novel itself.

But what of the time when he was a published author but The Remains of the Day had not yet made him a figurehead of British literature? These are the years when Ishiguro was working, writing, promoting his novels, and travelling internationally – and we’re pleased that on several occasions he worked with the British Council which colleagues here still recall with fondness.

Ishiguro travelled to Germany to appear at the British Council’s Walberberg Literature Seminar in 1987. He also made a number of trips to Japan including in 1989 his first to Japan since moving to the UK at the age of five. As Manami Yuasa, Head of Arts, British Council Japan, says: “In 1989 he was invited by the Japan Foundation through their Cultural Individual Invitation Programme. It was his first visit to Japan in 30 years. During his stay in Japan he had a dialogue with Kenzaburo Oe, another Japanese Nobel Prize winner, and also visited Nagasaki, his home town.” The conversation was published by the Japan Foundation, and the English translation can be found online here. David Elliott, Senior Programme Manager of the British Council’s Festivals and Seasons, adds that Ishiguro returned to Japan in 2001 at the invitation of his Japanese publisher Hayakawa Sobo, to promote the Japanese translation of When We Were Orphans, and again in 2011, when the British Embassy hosted a press conference for the film version of Never Let Me Go.

Paul Fairclough, Head of Corporate Planning, remembers meeting Ishiguro in Warsaw in 2005: “He gave a talk for us and did a book signing. I recall meeting him outside the bookstore and escorting him to the place where he was due to give his talk. I remember him being extremely polite and appreciative and very easy to talk to. I was inspired by his talk to buy a copy of Never Let Me Go which I thought was absolutely brilliant. If I remember correctly he spoke about the pace of the book – that it was deliberately not a rapid page turner, that he wanted readers to linger over the text.”

By the time of Never Let Me Go Ishiguro was a literary star, translated into 40 languages, but when he worked with Rebecca Walton – now the Regional Director for EU Europe at the British Council – he was at the start of this journey. Walton’s British Council work in the late 1980s involved connecting Nordic and British writers and publishers, to discuss and encourage translation of their works. She met Ishiguro in 1987, fostering the relationships that would lead to his work being translated into Danish, Finnish and Norwegian among other languages, and she remembers how young Ishiguro was compared to the other writers she had met – Germaine Greer, Angela Carter and Fay Weldon among them. He was travelling without his wife Lorna, she recalls, and was “looking for something special to take back”. When she mentioned a chocolate cake that was popular in the region – the Sarah Bernhardt Kager – he took a box of four back for his wife.

Most recently, Cortina Butler, Director of Literature at the British Council, attended a Nobel prize reception in Sweden, she said: “For the Nobel Laureates and their families the Nobel week is an intense programme of public events, receptions, school visits and press interviews. Each Laureate has to give a speech and Kazuo Ishiguro’s was a thoughtful and personal account of his development as a writer. A particularly illuminating moment is when he is talking about writing The Remains of the Day - “I wanted… to write 'international' fiction that could easily cross cultural and linguistic boundaries, even while writing a story set in what seemed a peculiarly English world. My version of England would be a kind of mythical one, whose outlines, I believed, were already present in the imaginations of many people around the world, including those who had never visited the country.” For me this lies at the root of his international success – why he is still a writer at the top of the list of invitation requests to the British Council.

The UK Ambassador in Stockholm gave a reception the day before the final Nobel ceremony for Kazuo Ishiguro and Richard Henderson, the Chemistry Laureate. Ishiguro, his wife Lorna and his daughter Naomi, were still points in a swirl of delighted publishers, agents, friends and Nobel luminaries, delighted and proud, dignified and generous. He is a worthy winner of this most extraordinary and life changing of prizes, as a writer and as a human being.”

Read the blog from Professor John Mullan here.