- ©

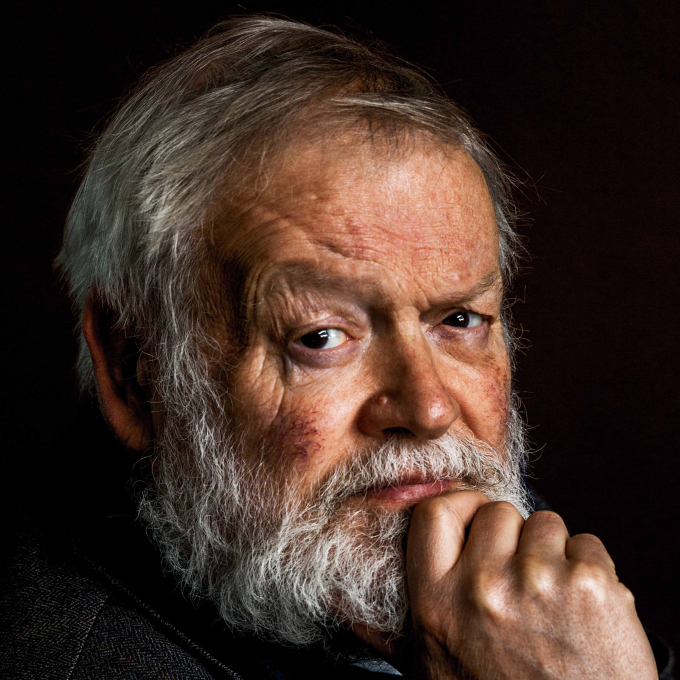

- Bobbie Hanvey

Michael Longley

- Belfast, Northern Ireland

- LAW (Lucas Alexander Whitley)

Biography

Poet Michael Longley was born in Belfast in 1939 and educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution.

After reading classics at Trinity College, Dublin, he taught in schools in Belfast, Dublin and London. He joined the Arts Council of Northern Ireland in 1970, working in literature and the traditional arts as Combined Arts Director before taking early retirement from the post in 1991. He was awarded the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 2001.

His first collection of poetry, No Continuing City: Poems 1963-1968, was published in 1969, and the collection Poems 1963-1983 was published in 1985. There was a 12-year gap between the publication of The Echo Gate: Poems 1975-1979 (1979) and the acclaimed Gorse Fires (1991), winner of the Whitbread Poetry Award. The Weather in Japan (2000), won the Hawthornden Prize, the T. S. Eliot Prize and the Belfast Arts Award for Literature. He is editor of 20th Century Irish Poems (2002).

Michael Longley was Writer Fellow at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1993. He has written widely on the arts in Northern Ireland, contributing to magazines including Encounter and Phoenix and has written scripts for BBC radio. He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a member of Aosdána, an affiliation of Irish artists engaged in literature, music and visual arts.

His Collected Poems was published in 2006. In 2007, he was appointed Professor of Poetry for Ireland, and his inaugural lecture, A Jovial Hullabuloo, was published in pamphlet form in the same year.

His most recent poetry collections are Gorse Fires (2009); A Hundred Doors (2011), shortlisted for the Forward Poetry Prize for Best Collection; The Stairwell (2014), shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize; and Angel Hill (2017), again shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection. His poem Marigolds,1960 was shortlisted for the 2012 Forward Poetry Prize for Best Single Poem.

Longley was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2010 Birthday Honours and in 2015 he received the Ulster Tattler Lifetime Achievement Award.

He lives in Belfast with his wife, the critic Edna Longley.

Critical perspective

‘Sir, if prose is a river, then poetry’s a fountain’, was Michael Longley’s only contribution to an undergraduate seminar on the Poetics as he recalls in a verse tribute to his old university in The Ghost Orchid (1995).

What might in another context seem trite is, in Longley’s case, an accurate description of how his own poetry bursts from the mainsprings of language and feeling. It signals too his gift as a lyric poet, whose structural creativity and observational acuity have flushed out the conventionality of the lyric form, and has brought to it a fresh set of engagements with traditional themes; nature and war, love and death.

Frequently described as one of the Belfast poetry ‘Group’ of the 1960s, Longley in fact owes more to the weight of English and classical tradition than to Irish antecedents or models. His acknowledged chain of influence extends from Philip Larkin and Ted Hughes to Louis MacNeice and W. H. Auden, and also extends to English poets of the First World War. From the classical literature he has pursued since undergraduate days, meanwhile, he derives both technical virtuosity and a deep well of allusion and paradigm. The ancient world provides him with a lens that refracts its modern counterpart, but which is itself suddenly illuminated by the passion and violence of contemporary society. If his forms and perspectives derive from elsewhere, Longley turns to Ireland to express his attachment to nature. With the authority of the botanist or naturalist, he has drawn into his poetry the flora and fauna of Ireland, perceived with extraordinary precision. In early collections, botanical and ornithological sequences depict the plant-life or birds of the countryside with an imagist flourish, rooted in scientific security. The kingfisher, in ‘The Corner of the Eye’ becomes ‘a rainbow / fractured against / the plate glass of winter’, the corolla of the foxglove, in ‘Botany’, ‘a thimble, / Stall for the little finger and the bee’.

In later work he continues to bypass the tame formalities of the pastoral, evoking instead the companionship of wild creatures and plants in his beloved County Mayo, in the west of Ireland, where he has spent much time in the same remote cottage for over 40 years:

‘The leveret come of age, snipe

At an angle, then the porpoises’

Demonstration of meaningless smiles.

Home is a hollow between the waves,

A clump of nettles, feathery winds,

And memory no longer than a day…’

('Remembering Carrigskeewaun')

Such intimate close-ups are a means of celebrating the natural world in all its perfection and diversity. But Longley’s engagement with nature also serves as a counter to his confrontations with urban life and the violence of his home city of Belfast. As a poet he has borne witness to the traumatic events of the Northern Irish Troubles, registering his outrage at paramilitary assassinations in journalistic poems such as ‘The Greengrocer’, or ‘The Civil Servant’. But where condemnation fails, he turns back to nature as a source of healing. In ‘The Ice Cream Man’, a murdered shopkeeper is offered a verbal wreath of Irish wild flower names: ‘Meadowsweet, tway blade, crowfoot, ling, angelica…’. Similarly in ‘The Fishing Party’, the poet composes a poignant litany for an off-duty policeman murdered on a fishing trip, listing the names of local fishing flies: ‘Dark Mackerel, Gravel Bed, Greenwell’s Glory, SoldierPalmer, Coachman, Water Cricket, Orange Grouse, Barm…’ These evocative taxonomies lift the subject from barbaric to elegiac, giving the poet a means, perhaps, of absorbing – though not accepting - his community’s persistent violence. In much of Longley’s writing, the Northern Irish conflict re-opens the deep wounds of previous wartime experiences. Several poems recall his father, who fought in two world wars, depicting him both as loved individual and as representative of a battle-scarred generation. Again, there is an attempt at healing through tribute, and through the redemption of love. In the dark comedy of ‘The Kilt’, the poet describes his father’s recurrent nightmare of stabbing a German soldier:

‘He had killed him in real life and in real life had killed

Lice by sliding along the pleats a sizzling bayonet

So that his kilt unravelled when he was advancing.

You pick up the stitches and with needle and thread

Accompany him out of the grave and into battle,

Your arms full of material and his nakedness.’

There are memories too of the battle of Somme in the First World War, its ‘cracked and splintered dead’ witnessed by proxy through Longley’s father (‘In Memoriam’), or linked in the poet’s mind to three teenage British soldiers and a bus driver, killed with brutal casualness during the early years of the Troubles (‘Wounds’). Like ‘Blitz’, which captures the suffering of Belfast during Second World War air raids in the image of dead children laid out in the city’s empty swimming baths, such poems rely on vivid, sometimes shocking detail, but serve to acknowledge the necessary place of death in the human imagination. In Gorse Fires (1991), Longley’s poetry seems to change gear slightly, with looser metric and varied verse forms, but his allusion to classical antecedents - particularly Homer - remains central and pertinent. In this volume’s graphic poem ‘The Butchers’, for example, the slaughter of Penelope’s suitors by the returning Odysseus is reconfigured in language which adds a contemporary nuance, glossing the episode with uncomfortable familiarity. In The Ghost Orchid, Ovid’s Metamorphoses forms the basis of a teasing philosophical series on the animal and human world, but here too, Homer predominates. The collection includes a poem Longley published in an Irish newspaper on the eve of the IRA ceasefire of 1994. Entitled simply ‘Ceasefire’, it draws on Book XXIV of the Iliad - in which Priam goes to Achilles to ask for Hector’s corpse – to contemplate the agonising process of forgiveness and renewal. An understated poem, it resonates deeply with the collective feeling of a shattered community, and signifies Longley’s continued commitment to the filtering – though poetry – of real life in its harshest forms.

In The Weather in Japan (2000), Longley chooses shorter forms, but pursues the contemplation of death and grieving introduced in The Ghost Orchid. Again his poetic landscapes cover a broad range, from Flanders to Auschwitz, but the emphasis throughout is on transcendent images which convey, like that of Homer’s horses weeping for Patroclus in ‘The Horses’, the twinned truths of love and suffering. And here, finally, is the resilient natural world once again – the fox, the hare, the seal – intimately realised, and offering consolation amidst the elegies and dark histories of the book.As in all Longley’s writing, a subtle lyric skill draws the collection together and charges it with his humane and instantly recognisable voice.

In Snow Water (2004) and A Hundred Doors (2011) Longley returns to familiar subjects: the nature and landscape of Carrigskeewaun, the First and Second World Wars, and, increasingly, his family. As in previous collections, poems are carefully ordered and arranged on the pages, so that they rub against and inform one another. There are a number of gently humorous pieces such as the self-deprecatory ‘Old Poets’, dedicated to a fellow-writer, Ann Stevenson, in which ‘Old poets regurgitate / Pellets of chewed-up paper / Packed with shrew tails, frog bones, / Beetle wings, wisdom.’ This sense of mortality is also present in the final poem of Snow Water, ‘Leaves’:

‘Is this my final phase?

Some of the poems depend

Peaceably like the brown leaves on a sheltered branch.

Others are hanging on through the equinoctial gales

To catch the westering sun’s red declension.

I’m thinking of the huge beech tree in our garden.

I can imagine foliage on fire like that.’

The remembrance of the First World War is an ongoing and vital project, movingly pursued in a series of short poems in A Hundred Doors. In 'Volunteer' a young groundsman cycles from the West of Ireland to the Western Front, 'his red / Neckerchief like a necklace of poppies.' Longley retains his delight in taxonomy, in the precision and lyrical potential of the correct name – in 'The Shetlands' he waits ‘at Toft for the Yell ferry' – but in ‘Wooden Sails’ a litany of English villages performs a similarly sombre function as the fishing flies a decade and a half earlier:

‘The ship of the fens is Ely Cathedral, its wooden

Sails becalmed below-decks like a gigantic ledger

Crammed with the names of unremembered soldiers

Under their villages' names - Shudy Camps, Little

Chishill, Abbingdon Piggots, Prick Willow, Swaffam

Bulbeck – until the sails billow with our lamentations

And the ship of the fens sets sail over the fens

To Fen Drayton, Ponders Bridge, Tadlow, Elm, Ely.’

Such an elegiac poem once again emphasises how Longley’s work presents a uniquely powerful bridge between English and Irish poetic traditions.

Dr Eve Patten with updated material by Dr Nick Turner, 2012