I began to teach myself Korean in 2010, spurred on by a nagging question: South Korea was a big country, presumably with a thriving literary scene, so why was there almost nothing on the shelves? I soon discovered the implicit biases that mean writing from non-European languages is much less likely to make it into English – editors unable to read the original language, authors not fluent in English, less likely to have agents or influential recommenders, harder to source funding. It will always be easier to finance a non-translation, just as it will always be easier to discover a non-translation, or a translation from a European language.

Five years later, a similar impulse led me to found Tilted Axis Press, which publishes cult, contemporary fiction from Asia.

Terminology is tricky, and I wanted to be clear that marginalised does not mean marginal. Hence our tagline: Tilting the axis of world literature from the centre to the margins allows us to challenge that very division. These margins are spaces of compelling innovation, where multiple traditions spark new forms and translation plays a crucial role.

In other words, Tilted Axis publishes the books that might not otherwise make it into English, for the very reasons that make them exciting to us – artistic originality, untold stories, “under-represented” languages.

A survey commissioned by the Man Booker International Prize found that in 2015, literary fiction accounted for 3.5% of the market, but 7% of sales, and that sales of translated fiction have almost doubled over the last 15 years. Many of the biggest-name authors are ones we read in translation: Murakami, Ferrante, Knausgaard, Han Kang. That's the good news.

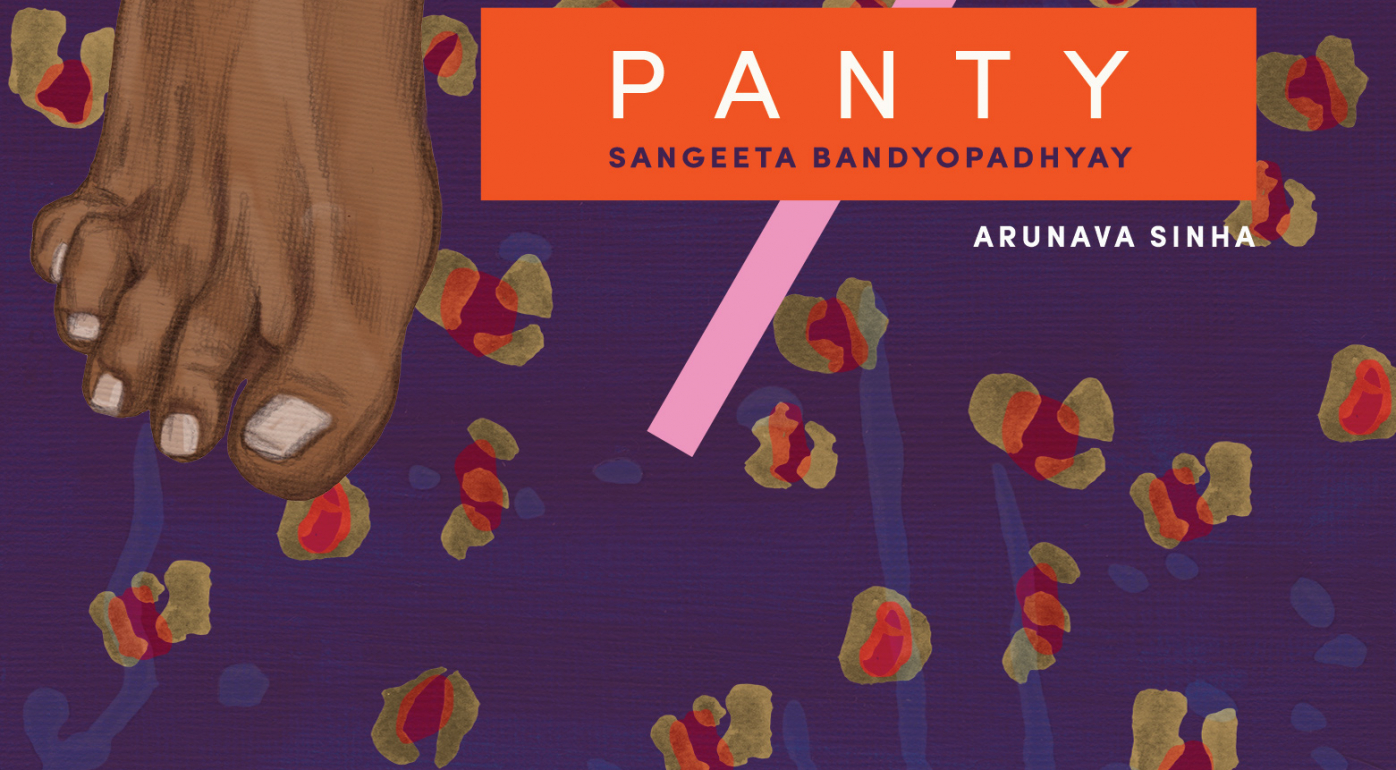

Only two of the top ten translated languages – Japanese and Arabic – were non-European, though twice as many account for the top ten by number of worldwide speakers. Not a single translation from the subcontinent was submitted for the Man Booker International – I know there was at least one this year, because Tilted Axis published it: Panty by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay, translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha. This year, we have the UK's first ever translations of contemporary fiction from Thai – Prabda Yoon's The Sad Part Was, for which Mui Poopoksakul's translation has also received rave reviews – and Uzbek, from established author Hamid Ismailov and his enterprising translator Donald Rayfield, who taught himself the language for this project.

But as proud as I am of all this, the rarity is hardly a cause for celebration.

It's such tiny numbers that makes representation an issue, when it shouldn't have to be, by exacerbating publishing's tendency towards essentialising and stereotyping. It's extremely disingenuous for publishers to loftily claim they assess each book solely on its artistic merits, as though their own taste – and the taste of their often majority-white teams – could not possibly be subjective, and as though all of the biases I listed above simply aren't a factor. Publishing books that excite us because of their artistry is not mutually exclusive with an awareness of the factors that are shaping our choice, and neither is it defensible while the media continues to perpetuate reductive, damaging narratives – or deafening silence.

Because there is a case to be made for translation, and it isn't to offer 'a window onto another culture' (though perhaps, if the windows weren't so selective, what we see through them wouldn't seem so other) but to represent literary cultures that we're not currently getting access to.

Diversity of languages, cultures, nationalities etc. is important from a representational standpoint, but what I most want to explore with Tilted Axis are varieties of form, of style, and language, and the way these offset and/or form part of what we think of as the book's 'subject'.

For one thing, many literatures outside the Euro-bubble don't set such overwhelming stock in the novel (or at least the novel as we think of it), which means their strength might be in short fiction – most of Tilted Axis' titles are under 200 pages – or in poetry.

Translation is not about eating your greens, but it does do us good. Working with under-represented languages is good for translators, affording them the opportunity to act as curators for the literature they're passionate about – another reason it's imperative that translators be judged solely on their ability to manipulate the English language, not the stage of life at which they acquired it – and to be more involved with publicity, for which they should always be paid. It's good for publishers, helping their books stand out in a saturated market and enabling tiny start-ups like Tilted Axis to snap up writing of incredible quality for which, as the numbers show, there's a growing readership.

And in these times of rising bigotry and xenophobia, it can only be good for society and culture as a whole. The wonderful Comma Press should be lauded not only for committing to exclusively publish work from Trump's Muslim ban countries in 2018, but for the fact that they were one of the few UK presses already championing literature from Iraq, Sudan, Bangladesh, and Palestine. We shouldn't have to wait for a humanitarian crisis to be able to read a given country's literature, and nor should we limit the scope of its narratives to poverty, oppression, or terrorism.

The positive news is that a spate of new initiatives suggest that times are changing.

As well as the MBI itself, there's Warwick University's Women in Translation Prize; this year's Harvill Secker Young Translators' Prize is being given for Korean, and the winner will also get one of Writers Centre Norwich's coveted literary translation mentorships (I'm thrilled to have been asked to be judge and mentor). Last week at the London Book Fair, they announced that the upcoming roster of languages will also include Tamil and Malayalam – brilliant news coming just after a panel I chaired on how to expand the range of languages making it through. Clearly, the margins are where it's at.