- ©

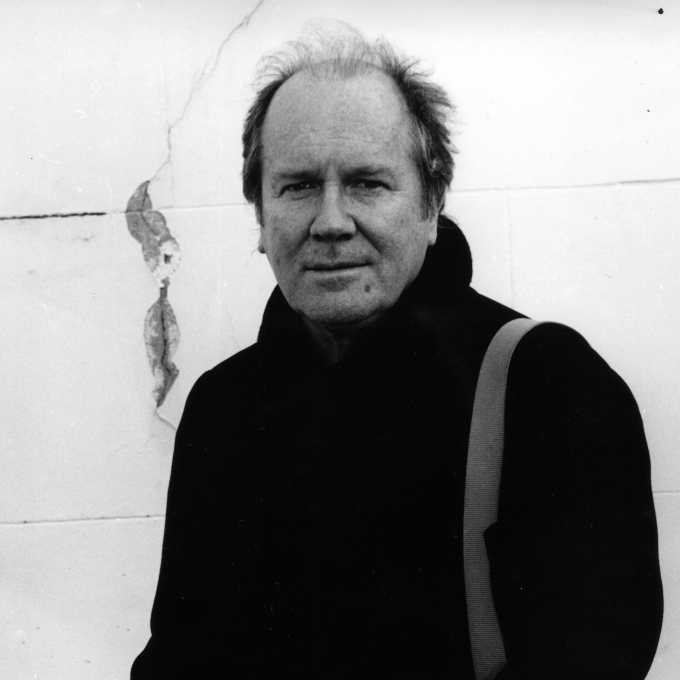

- Marzena Pogorzaly

Biography

William Boyd was born in Accra, Ghana, on 7 March 1952.

He was educated at Gordonstoun School, Glasgow University and Jesus College, Oxford. Published while he was a lecturer in English at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, his first novel A Good Man in Africa (1981) won the Whitbread First Novel Award and a Somerset Maugham Award. In 1983 Boyd was named by Granta as one of the 20 ‘Best of Young British Novelists’.

His other novels include An Ice-Cream War (1982), winner of the Mail on Sunday/John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, Brazzaville Beach (1990), which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction and the McVitie’s Prize for Scottish Writer of the Year, and The Blue Afternoon (1993), which won the Sunday Express Book of the Year award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize (Fiction). Armadillo (1998) is set in London and follows the adventures of insomniac loss-adjuster Lorimer Black. In 1998 Boyd also published Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960, an elaborate hoax ‘biography’ of a neglected genius, which embarrassed a number of prominent art critics who claimed to have heard of the wholly fictional painter.

Boyd’s eighth novel Any Human Heart (2002), a history of the twentieth century told through the fictional journals of the novelist Logan Mountstuart, won the Prix Jean Monnet for European Literature in 2003 and was nominated for the 2004 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Restless (2006) won the 2006 Costa Novel Award. His most recent novels are Ordinary Thunderstorms (2009) and Waiting for Sunrise (2012).

Boyd has also published the short story collections On the Yankee Station (1981), The Destiny of Natalie ‘X’ (1995), Fascination (2004) and The Dream Lover (2008), and a collection of non-fiction, Bamboo (2005).

A former television critic for the New Statesman (1981-3), William Boyd has also worked extensively as a screenwriter for both film and television. He wrote the television screenplays Good and Bad at Games (1983) and Dutch Girls (1985) (collected in book form as School Ties in 1985), and has adapted two novels by Evelyn Waugh for television: Scoop (1987) and Sword of Honour (2001). He wrote and directed the First World War film The Trench (1999) and has also adapted his own novels Stars and Bars (1988) and A Good Man in Africa (1994) for film, and Armadillo (2001), Any Human Heart (2010) and Restless (2012) for television.

A new radio play, the ghost story A Haunting, was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in December 2001. Longings, adapted from two short stories by Anton Chekhov and Boyd’s first work for the stage, opened at the Hampstead Theatre in London in February 2013.

In 2012 Boyd was commissioned by the Ian Fleming estate to write an official James Bond novel, which was published in 2013 on the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of Fleming’s Casino Royale. Fleming himself made a cameo appearance in Any Human Heart.

William Boyd lives in London. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1983, and is also an Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. He was awarded a CBE in 2005.

He is married and divides his time between London and South West France.

Critical perspective

William Boyd is perhaps best described as a wry historian of 20th-century life, and an ironic commentator on the ways that life has been represented, not only in literature, but in the companion genres of visual art, film and photography.

While his geographical settings vary from the conflict-stricken west African coast of Brazzaville Beach (1990) to the romantic vistas of the Philippine islands in The Blue Afternoon (1993), his recurrent character focus is the English personality and how it adapts – or fails to adapt – to the demands of a foreign landscape. Like Henderson Dores, the introverted Englishman turned extrovert Manhattanite in Stars and Bars (1984), Englishness under pressure is seen to undergo the most radical metamorphoses, and yet remain, at the same time, irrepressibly resilient.

In his 1981 debut novel, A Good Man in Africa, Boyd displayed his affiliation to an English tradition of the comic novel of expatriate life, together with his allegiance to one of his many literary mentors, Evelyn Waugh. In the figure of Morgan Leafy, a hapless British diplomat struggling to master the complexities of his posting to a corrupt west African country (the fictional Kinjanja), Boyd also echoed the post-war formula of the ‘Angry Young Man’, his bumbling, gauche, but ultimately sympathetic protagonist even leading some critics to hail the author as a natural successor to Kingsley Amis (D. J. Taylor, After the War (1993, xxi). Like Amis’s Jim Dixon in the 1954 comedy Lucky Jim, the accident-prone Leafy pursues his love interest through a series of career crises and ham-fisted sexual encounters, ‘an aristocrat of pain and frustration, a prince of anguish and embarrassment’, until he eventually regains his girl, and his self-respect, against all the odds of his situation.

But Boyd’s first novel also hinted at his sensitivity to Africa as a continent bedevilled by poverty, exploitation and misguided foreign interference. His portrait no doubt builds on his own childhood experiences in Ghana, something he discusses in the autobiographical essay included in his 1998 Protobiography. Though perpetually self-absorbed, Leafy nonetheless registers the misery and decrepitude of his surroundings in the overpopulated capital of Nkongsamba. ‘Set in undulating tropical rain forest, from the air it resembled nothing so much as a giant pool of vomit on somebody’s expansive unmown lawn.’ And while the plot of A Good Man is driven by a comedy of diplomatic manners, the novel also conveys the heat, sweat, and endless frustrations of a crumbling post-imperial system, with the chaos of a continent throwing into relief a legacy of British incompetence.

Boyd addressed this subject with more seriousness in his second novel, An Ice-Cream War (1982), which delves into the clashes between British and German forces in the East Africa campaigns of the First World War. The historical and military material of this book is recreated in vibrant detail, and in his intense descriptive passages Boyd brings out the full colour and desolation of the ravaged landscape of Tanzania. The African scenes are intercut with episodes set in Kent, in the south of England, telling the parallel stories of two brothers, Gabriel and Felix Cobb, whose lives change irreparably as they are drawn, one after the other, into the war. The quiet civility of Edwardian England contrasts starkly with the confusion and panic of the Africa conflict, experienced first-hand by Gabriel, as he leads his regiment into an attack on the town of Tanga:

‘Nothing today had been remotely how he had imagined it would be; nothing in his education or training had prepared him for the utter randomness and total contingency of events. Here he was, strolling about the battlefield looking for his missing company like a mother searching for lost children in the park.’

When Gabriel is taken prisoner, his brother Felix searches for him in an African landscape transformed into an absurd nightmare of squalor, insects, torrential rain and countless human casualties. And the novel swings ultimately from romance to elegy, providing a brilliant evocation of the long reach of war behind the front lines and into ordinary domestic existence.

Much of Boyd’s writing utilises the awkward intersection of private and public life, and the suffering of individuals who – like the unfortunate protagonist of his screenplay Good and Bad at Games (1983) – cannot match the cultural demands of their environment. In this respect, he is also intrigued by the way in which individuals register the intimate details of their lives, something which developed into his use of a diary or journal form in several novels. In Armadillo (1998), a low-level thriller set in a London insurance company, the central character’s journal is his means of containing and interpreting the nature of coincidence, chance, unpredictability and risk in everyday life. And a diary of sorts provides the basis for Boyd’s 1987 epic, The New Confessions, in which film-maker John James Todd’s overriding obsession with Rousseau’s Confessions becomes the basis for his own confessional memoir of a life lived, through war, romance and ambition, in tandem with the twentieth century.

The New Confessions showcases not only Boyd’s superb historical instinct but also his ability to perceive the significance of modern cultural representation through the evolution of photography, journalism and cinema. In this novel, the story of the heyday and decline of silent movies and B-westerns underlines the idea that art forms, like people, have their own biographies. The author’s attention to this fact, and to the gaps which emerge between imagination and finished work, later fuelled his 1998 spoof on the New York art world, Nat Tate, and also his forays into architecture, film and music in short fiction.

But Boyd’s most daring commentary on artistic representation – and indeed, his most ambitious use to date of the fictionalized diary format – is reserved for an engrossing commentary on literature itself. Any Human Heart (2002), the journal of Uruguayan-born, British-bred writer Logan Mountstuart, spans the defining episodes of the twentieth century and crosses several continents in tracking the meandering life of a modern man-of-letters through a convoluted sequence of relationships and literary endeavours. Again, the diary is a means of exploring how public events impinge on individual consciousness, so that Mountstuart’s journal alludes almost casually to the war, the death of a prime minister or the abdication of the king. But Boyd also uses it to play ironically on the theme of literary celebrity, bringing his protagonist into contact with a series of ‘real’ writers in a sequence of comic or petty encounters – a spat with Virginia Woolf in London, a possible sexual encounter with Evelyn Waugh at Oxford, a clumsy exchange with James Joyce in Paris over the translation of the term ‘scribouillard’.

Any Human Heart is a self-consciously clever novel, a 20th-century picaresque conceived in the tradition of Anthony Powell or Anthony Burgess, and loaded with veiled tributes to Boyd’s literary heroes Cyril Connolly and William Gerhardie, whose flamboyant and affected styles haunt Mountstuart’s own prose. It signals too, towards Boyd’s lingering feelings of uneasiness with colonialism and the British establishment, which he also explores in several of the essays collected in Bamboo (2005). Any Human Heart is also, more simply, a rich and frequently moving study of the inevitability of life’s passage. The elderly Mountstuart, watching teenagers on a French beach, is struck by the simplicity of this fact:

‘And suddenly I wonder; is it more of my bad luck to have been born when I was, at the beginning of this century and not be able to be young at its end? I look enviously at these kids and think about the lives they are living – and will live – and posit a kind of future for them. And then, almost immediately, I think what a futile regret that is. You must live the life you have been given.’

Boyd has argued that ‘like a vitamin pill, a good short story can provide a compressed blast of discerning intellectual pleasure, one no less intense than that delivered by a novel’ (The Guardian, 2 October, 2004). It could be said that both his stories and his novels are governed by the ideal of a ‘discerning intellectual pleasure’, sustained by his ability to marry individual interest with historical scope, and to fuse conceptual purpose with the power of compelling narrative. This combination is pursued once again in Restless (2006), a less emotionally involving novel than Any Human Heart, but which similarly highlights Boyd’s ongoing preoccupation with recreating the scenes and textures of 20th-century history. The novel has two female protagonists: Ruth Gilmartin, a postgraduate student in 1970s Oxford, and her mother Sally, whose eccentric and homely English exterior masks a previous existence as Russian émigrée Eva Delectorskaya, and whose wartime career in espionage has returned to haunt her 30 years later. The narrative of Restless alternates between Ruth’s investigation into her mother’s past, and Eva’s own account of her life as a spy, working for the secret British Security Coordination organisation in Belgium, London and, most importantly, the United States, as Boyd mines submerged histories of British wartime propaganda and American Anglophobia to weave a tense and complex web which threatens to undermine post-war myths of a ‘special relationship’ between the two powers.

As Eva gradually involves her daughter in her plans for revenge on her former spymaster with whom she was romantically involved, the novel displays many of the conventions of a romantic thriller, and in the constant role-playing and double bluffing occasioned by the spy genre, personal relationships and allegiances are perpetually at risk. In sharp contrast to the confident personal narrative of Any Human Heart, Restless marks a return, of sorts, to some of the awkward convolutions of identity which flavoured Boyd’s early fiction, and to a British social landscape still troubled by ingrained historical insecurities.

Boyd returns to the thriller genre in his tenth and eleventh novels Ordinary Thunderstorms (2009) and Waiting for Sunrise (2012). With a nod to John Buchan’s The 39 Steps, Ordinary Thunderstorms opens as Adam Kindred, a divorced climatologist, arrives in London for a job interview and almost immediately becomes incriminated in a murder. Unlike Buchan’s protagonist, however, Kindred decides to remain in London, abandoning his identity and initially living rough on a piece of waste ground in Chelsea, existing on handouts and charity, as he tries to piece together the circumstances of the killing. Kindred’s profession is something of a red herring, and inasmuch as the novel has any contemporary target it is the international pharmaceutical trade: the murdered man had been developing a new cure for asthma, and Kindred is in possession of a file which casts doubt on the effectiveness of the new drug, leading to a brutal manhunt by private security operatives.

This is Boyd’s London novel, and there are obvious Dickensian echoes in Kindred’s experiences in the underworld, and in the way that Boyd seeks to draw characters from disparate social backgrounds into his narrative. The course of this thriller is perhaps hindered by the number of digressions and subplots, and its pace is often as leisurely as the River Thames around which much of the action unfolds.

A false accusation also sets the plot of Boyd’s subsequent novel in motion. In Waiting for Sunrise, Lysander Rief travels to Vienna in 1913, seeking therapeutic treatment for an embarrassing sexual problem. There he falls into a tempestuous relationship with a fellow patient, the neurotic sculptress Hettie Bull, who after some months accuses him of rape. Indebted to a shadowy pair of attachés at the British consulate who enable his escape to England, on the outbreak of war Rief is compelled to become involved in a complex operation to trace the leaking of details of military movements on the Western Front to Germany. The early sessions of therapy offer a convenient means of establishing the back story of the Anglo-Austrian protagonist, whose pre-war employment as an actor and facility for disguise prove central to his mission, which offers Rief ‘the chance to see the mighty industrial technologies of the twentieth-century war machine both at its massive, bureaucratic source and at its narrow, vulnerable human target.’

Waiting for Sunrise displays some familiar Boyd preoccupations, including the ekphrastic description of invented works of art and references to the early days of cinema, and the novel demonstrates his enduring interest in recreating specific historical and cultural milieux: initially Vienna immediately before the First World War (there is a cameo appearance by Sigmund Freud) and subsequently wartime London, with brief sorties to the trenches of the Western Front and to Geneva. Like previous works, the novel has an important confessional dimension, as the narrative is interspersed with extracts from Rief’s journals, which permit some formal innovation in the inclusion of some poems and some fragments of dialogue rendered in playscript.

Boyd’s recent success in refreshing the conventions of spy fiction should serve him well in his forthcoming project of writing the next official James Bond novel, published in 2013.

Dr Eve Patten, 2008, Dr Guy Woodward, 2013