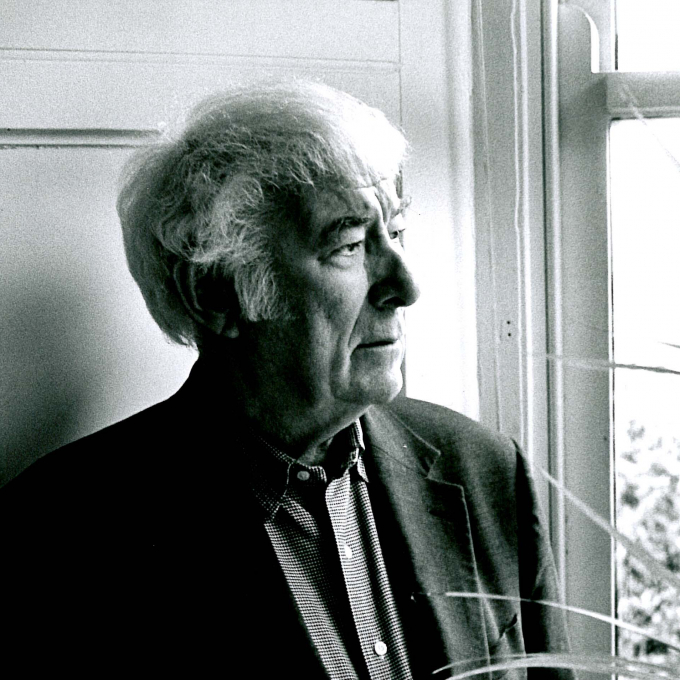

- ©

- John Minihan

Biography

Irish poet Seamus Heaney was born on 13 April 1939 in County Derry, Northern Ireland, the son of a farmer.

He was educated at St Columb's College in Derry and Queen's University, Belfast, graduating in 1961. He taught at Queen's University, Belfast, between 1966 and 1972 and was a visiting lecturer at the University of California in 1970/71. He moved to the Republic of Ireland in 1972. He was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University between 1989 and 1994, Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University (formerly Visiting Professor) between 1985 and 1997 and Ralph Waldo Emerson Poet in Residence at Harvard University between 1998 and 2006. Seamus Heaney is a member of Aosdána, an affiliation of artists engaged in literature, music and visual arts in Ireland, and the Irish Academy of Letters and is a Fellow of the British Academy. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995.

Much of his early poetry is heavily influenced by his rural upbringing and includes Death of a Naturalist (1966), winner of a Somerset Maugham Award and a Cholmondeley Award, and Door into the Dark (1969). Later collections, including North (1975), winner of the WH Smith Literary Award and the Duff Cooper Prize, and Field Work (1979), show wider political and social concerns. Other collections include The Haw Lantern (1987), winner of the Whitbread Poetry Award; The Spirit Level (1996), winner of the Whitbread Book of the Year; Electric Light (2001), and Human Chain (2010).

Seamus Heaney's adaptation of Sophocles' Philoctetes, The Cure at Troy (1990), was written for the Field Day theatre company. His translation of Beowulf (1999) won the Whitbread Book of the Year award. His non-fiction includes three books of essays Preoccupations (1980), The Government of the Tongue (1988) and The Redress of Poetry (1995) and a new collection entitled Finders Keepers: Selected Prose 1971-2001 (2002). Recent work includes The Burial at Thebes (2004), a verse translation of Sophocles' Antigone; District and Circle (2006), which won the 2006 T. S. Eliot Prize; and a translation of the Middle Scots poems of the 15th-century poet, Robert Henryson.

His last collection is Human Chain (2010), winner of the 2010 Forward Poetry Prize (Best Poetry Collection of the Year) and shortlisted for the 2010 T. S. Eliot Prize. Seamus Heaney died in 2013.

Critical perspective

Seamus Heaney is the most well-known and probably the most significant and influential English-language poet in contemporary literature.

He was brought up in a Catholic family in a rural farming community in Northern Ireland, and as an adult moved to the Republic of Ireland. Heaney objected strongly to being included as a ‘British poet’ in The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry (1982, ed. Morrison and Motion), and expressed his response in verse: ‘Be advised! My passport’s green. / No glass of ours was ever raised / To toast The Queen.’ Heaney’s literary influences, however, are quite diverse, and include the classics of both English and Irish poetry (Wordsworth and Hughes; Yeats and Kavanagh, among others), as well as an increasingly international influence. His later work has been likened to Dante, and also shows the influence of Eastern European poets such as Czeslaw Milosz and Miroslaw Holub.

One of Heaney’s most famous poems is ‘Digging’, from his first collection, Death of a Naturalist (1966). In this and other early works, his poetic material was the rural farming life and community of Ulster, including his own family roots. Even in later works, although Heaney broadens his themes and subject matter, rural Northern Ireland is a continued presence. In ‘Digging’, he asserts that while his father and grandfather before him dug the Irish land as farmers, he will ‘dig’ with intellectual and poetic exploration:

'Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, digging down and down [...]

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.'

Yet, while his own path is one of education, he has the greatest respect for the work and lifestyle of his forebears. In ‘Digging’ and other poems, the feeling conveyed is that the poetic sensibility has emerged from his rural ancestry and community, and is deeply rooted in it – there is not a conflict, but an allegiance between the two: ‘the curt cuts of an edge / Through living roots awaken in my head.’

When Heaney received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, the award citation praised the ‘lyrical beauty’ of his poetry. From the earliest works, Heaney’s language is deeply sensuous, evocative and musical, delighting in the sounds of words. Consequently, his imagery is rich and vivid: ‘the squelch and slap / Of soggy peat’; ‘the plash and gurgle of the sour-breathed milk’. Within the rich, earthy language and the reverence for communal life and Irish landscape, however, there is also the hint of violence and unrest: ‘Between my finger and thumb / The squat pen rests, as snug as a gun.’

In 1969, British troops were deployed in Belfast, marking the beginning of The Troubles. In his essay collection, Preoccupations (1980), Heaney discussed the way in which his approach to poetry began to shift: ‘the problems of poetry moved from being simply a matter of achieving a satisfactory verbal icon to being a search for images and symbols adequate to our predicament.’ In Wintering Out (1972) and, even more significantly, North (1975), the focus of Heaney’s poetry broadened to encompass the wider social and political context, enabling him to engage with the contemporary Irish situation without compromising his artistic concerns. He was influenced by his reading of The Bog People by P.V. Glob, perceiving an analogy between the Iron Age victims of ritualistic violence and the modern-day victims of violent atrocities in Northern Ireland. This enabled him to intertwine mythic and contemporary concerns: in poems such as ‘Punishment’ and ‘Strange Fruit’, which comment on images of the ‘bog people’, Heaney is indirectly expressing collective despair and disgust at the barbarity that was pervading contemporary Northern Irish communities. In his graphic images of the tortured bodies, he utilises the same gift for multi-sensory detail with which he had so vividly depicted rural life in the early poems. These images confront the reader quite explicitly with the reality of violence, both past and present:

‘your brain’s exposed / and darkened combs, / your muscles’ webbing / and all your numbered bones’

‘Her broken nose is dark as a turf clod, / Her eyeholes blank as pools in the old workings.’

During the 1970s, Heaney and his family moved to the Republic of Ireland. Collections such as Field Work (1979) and Station Island (1984) are widely regarded by critics as signalling a further shift in Heaney’s development as a poet, in which the perspective of the poetry looks outward as well as inward. From Field Work onwards, as Stan Smith comments, Heaney’s poetry is ‘poised equivocally between the local [...] and the larger field of meanings within which that life now finds itself’ (Heaney entry in Contemporary Poets, 1991). Many of these poems explore the way in which physical distance from one’s home environment can aid the development of psychological detachment and a clearer perspective. Yet, simultaneously, there is a sense of inner conflict, guilt at those who have been left behind, and an attempt to reassure oneself: ‘Let go, let fly, forget. / You’ve listened long enough. Now strike your note.’

Station Island has a Dante-esque feel to it, and this continues in The Haw Lantern (1987), which also shows the influence of Eastern European poetry. Other later works, including Seeing Things (1991) and The Spirit Level (1996), continue in meditative and self-reflective mode, particularly with regard to the role and responsibility of the poet in society and the desire to strike a balance between artistic and socio-political concerns. In his second collection of essays, The Government of the Tongue (1988), Heaney comments: ‘Poetry is its own reality, and no matter how much a poet may concede to the corrective pressures of social, moral, political and historical reality, the ultimate fidelity must be to the demands and promise of the artistic event.’

Electric Light (2001) has a positive and celebratory tone and, like many of Heaney’s collections, combines a variety of different types of poem. It is divided into two sections, the first of which includes translations of Virgil and other poems with classical reference, along with poems of childhood and celebrations of birth, such as the delightful ‘Out of the Bag’, in which a child narrator believes that babies come in parts, ready to be assembled by the doctor:

'little, pendent, teat-hued infant parts

Strung neatly from a line up near the ceiling [...]

The baby bits all came together swimming

Into his soapy big hygienic hands [...]'

After these poems of birth, the second section of Electric Light consists of poignant elegies to the deceased: some to poets, such as Ted Hughes and Joseph Brodsky, and some to old friends and family members. Sadness over these losses is lightened by happy memories and an acceptance of the ebb and flow of life.

District and Circle (2006) continues in a similar vein, celebrating the cycle of life and offering praise to poet-ancestors, including Hughes once again, Wordsworth, Auden and Rilke. Other poems allude to modern-day fears – environmental issues, terrorist attacks and Ireland’s fragile peace. Andrew Motion’s review of District and Circle celebrates the way in which, throughout his career, Heaney has displayed a remarkable ability to ground the transcendent in the everyday: ‘He’s interested in the numinous and transcendent, all right, but he generally takes flight from recognisable rural origins. The extraordinary is implicated in the ordinary – and vice versa’ (The Guardian, 1 April 2006).

This gift for both illuminated insight and down-to-earth accessibility, expressed so poignantly in ‘Digging’, the first poem of his first volume, probably explains why Heaney has attained both immense critical acclaim and a wide readership. It is particularly apparent in his translation work, most notably Beowulf (1999), which became a best-seller – quite a remarkable feat for any work of poetry, particularly a translation of a ‘highbrow’ and previously inaccessible work. As in much of his earlier work – particularly the poems inspired by The Bog People – Heaney’s Beowulf draws parallels between the past and the present, using ancient stories to comment indirectly on contemporary situations, particularly mankind’s propensity to violence and brutality. Heaney’s other translations include Sophocles: The Cure at Troy (1990) (adapted from Sophocles’ Philoctetes) and The Burial at Thebes (2004) (adapted from Sophocles’ Antigone). He has also translated Robert Henryson’s The Testament at Cresseid (2006). All these works have been critically acclaimed, although none have attained the wide readership of Beowulf.

Elizabeth O’Reilly, 2010

For an in-depth critical review see Seamus Heaney by Andrew Murphy 2nd edition (Northcote House, 2000: Writers and their Work Series).