- ©

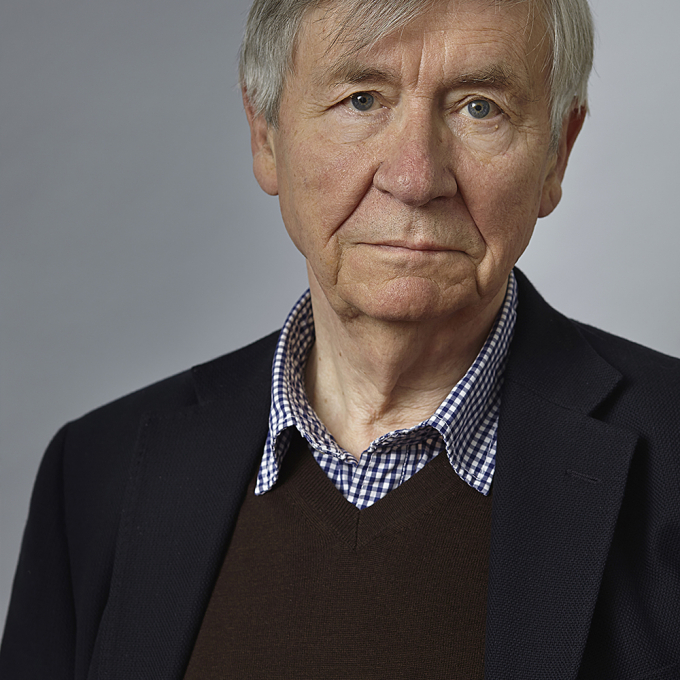

- Jonathan Ring

Piers Paul Read

- Beaconsfield, England

Biography

Novelist and playwright Piers Paul Read was born in Beaconsfield on 7 March 1941.

He was educated at Ampleforth College and St John's College, Cambridge, where he read History.

He was Artist in Residence at the Ford Foundation in Berlin (1963-4), Harkness Fellow, Commonwealth Fund, New York (1967-8), a member of the Council of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (1971-5), a member of the Literature Panel at the Arts Council, (1975-7), and Adjunct Professor of Writing, Columbia University, New York (1980). From 1992-7 he was Chairman of the Catholic Writers' Guild.

His first novel, Game in Heaven with Tussy Marx, was published in 1966. His second novel, The Junkers (1968), won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize. Monk Dawson (1969), won the Hawthornden Prize. More recent novels include The Free Frenchman (1986), set in France during the Second World War; A Season in the West (1988); On the Third Day (1990) and A Patriot in Berlin (1995), a political thriller. Alice in Exile (2001), is the story of a young Englishwoman caught up in the Russian Revolution.

His non-fiction includes Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors (1974), an account of the aftermath of a plane crash in the Andes, later adapted as a film; Ablaze: The Story of Chernobyl (1993), the story of Russia's worst nuclear disaster; and The Templars (1999), a history of the Crusades. His latest books are: Alec Guinness (2003), an authorised biography of the acclaimed late actor; and Hell and other essays (2006).

Piers Paul Read has also written a number of television plays, and several of his novels have been filmed for cinema and television. He lives in London.

His latest book is The Death of a Pope (2009).

Critical perspective

Reviewing Piers Paul Read’s most recent novel, The Death of a Pope (2009), Michael Coren wrote that ‘If there were any justice in the world of letters, [Read] would be spoken of with Amis, Barnes, Rushdie and the rest of the dominant literary class whenever the great contemporary British novelists were mentioned’.

The fact, of course, is that he is not; for various reasons his work has become unfashionable, although fashion and quality do not always go hand in hand. He is best known for Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors (1974), chiefly because this work became a successful film; he has also written history, biography and screenplays. But he has in addition written 15 accomplished novels that deserve attention: his older work has criminally been allowed to go out of print, although his 1970s novels are some of the best of that period in English fiction.

Read’s second novel, The Junkers (1968), which won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, sees the author marking himself out as different and even controversial, early on in his career: the focus is on life in Germany after the Second World War, seen through characters with a lineage back to a feudal past. There is a rewarding background of post-war German history here; the images of decay and atrophy are accompanied by a pro-European vision that permeates the end of the novel. Most interesting of all is the narrator’s stated attempt to ‘imagine’ the lives of the medieval von Rummelsbergs, the ancestors of the woman he is voyeuristically attracted to: the history in the novel should be thus treated with scepticism. Monk Dawson (1969) begins Read’s interest in an individual in conflict with the morals and ideals of their surrounding society; its most memorable scene, where an upper class dinner party descends into a mock Black Mass and vomiting, shows Read as a more sober inheritor of the terrain of Evelyn Waugh. This class focus grows in subsequent work as, of course, does the religious focus, for Read is Britain’s most Catholic novelist since Graham Greene. The protagonist’s circular journey from a boarding school run by monks, out into society, and back, paints a picture of both a corrupt secular world, and a Church that destroys its children.

Read, then, has a bleak picture of humanity, which originates in his Catholicism. It will find its forte in his strongest novel, The Upstart (1973). Hilary, the son of a Yorkshire priest, seems to exist by accident, as is revealed in a wonderfully bitter and terse opening:

'In the spring of 1938 a curate was admitted to the Charing Cross Hospital in London for the removal of a stone from his bladder. Sponging his puny body … there was a nurse who spoke with a soft and pleasant Yorkshire accent. The curate and the nurse fell in love. The healthy, buxom farmer’s daughter formed a passion for the clergyman’s gentility; and the bloodless cleric had the aberrant spirit to think of his hand under her starched skirts. The couple were later married and I was their only child.'

Brought up by middle class parents who aspire to the lives of the local landowners (it is as if Hilary is the son of Jane Austen’s Mr. Collins), and then mocked by them, we see the protagonist develop a sense of hatred for the class above him – and for the world in general. Read’s novel lets Hilary tell his own story, bringing the reader uncomfortably close to the evil he propagates: adultery, seduction of virgins, running a brothel, murdering a newborn baby and framing an old friend for near manslaughter are only some of the items on the list. Iris Murdoch’s complaint that British fiction presented no convincing pictures of evil is disproved with Read, who in this novel seems both repelled by and fascinated by sin. The final scenes, where (after sharing a prison cell with a masturbating criminal) Hilary returns to God, marries the daughter of the once-hated landowners and thus becomes the patriarch, may seem forced, but they allow The Upstart to be read as a modern version of a typical 18th-century morality tale such as Moll Flanders. Best of all is a teasing comment from Hilary’s wife, as she reads the written version of his life: ‘If you ask me, half of it’s your imagination’.

Sin and redemption, however, are only some of Read’s themes. The Professor’s Daughter (1971) is, as D. J. Taylor (another Catholic novelist and long-time Read admirer) pointed out, the alternative version of Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man: if the latter takes a comic look at the effects of the 1960s, Read’s work is definitely tragic. A sharp, idiosyncratic look at the current political and social climate is similarly provided by another of Read’s strongest novels, A Married Man (1979). This is a state-of-the-nation novel which again shows a middle class character struggling angrily against the upper classes which both attract and appal him.

Read’s novels of the 1980s and beyond show him widening his focus, returning to the territory of the The Junkers to examine morality in the face of war in novels such as The Free Frenchman (1988). Again, the focus is on Europe: Read is a refreshingly anti-provincial writer, and by this point we can see him maintaining a strongly individual path in opposition to the literary establishment: his work is strongly realist, with a great interest in character and reported thought. Not only that, something that should be a blessing can be seen by some critics as a curse: Read is unashamedly interested in plot, and his later novels may be dubbed as superior ‘spy fiction’ or ‘political thrillers’. Alice in Exile (2001), for example, inhabits ground made popular by Sebastian Faulks in Birdsong: historical fiction set in the First World War, with a strong element of romance.

Throughout his work Read uses a style that manages to be formal, readable and interesting at the same time; the tone is direct and educated, and there are frequent generalisations from an omniscient narrator, in the manner of George Eliot. It cannot be denied that Read’s Catholicism and right-wing politics, and his thoughts on feminism and homosexuality, are out of kilter with the modern literary world; that does not mean that he has not written novels of great interest. D.H. Lawrence, Evelyn Waugh and many others have objectionable politics, but it does not make them lesser artists. Such is the case with Read.

Dr Nick Turner, 2009