Biography

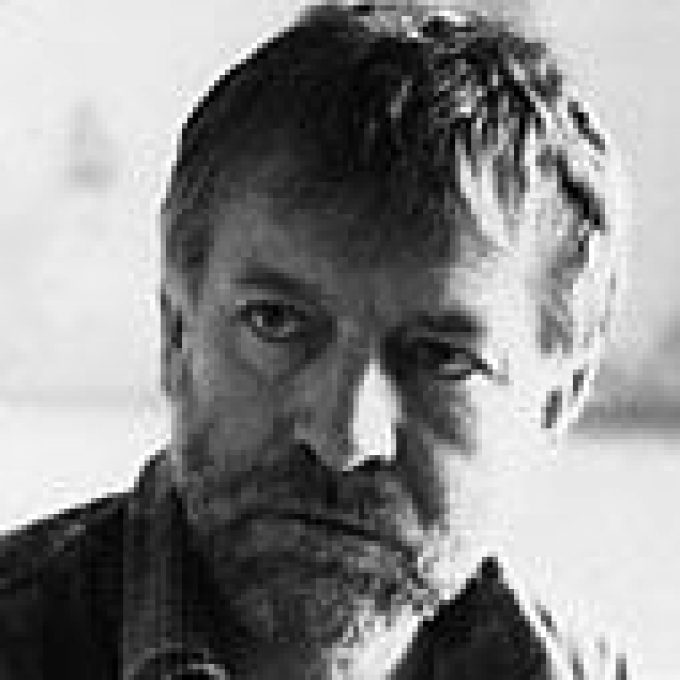

Poet Peter Reading was born on 27 July 1946 in Liverpool, England.

He worked as a school teacher in Liverpool (1967-8) and at Liverpool College of Art where he taught Art History (1968-70). He was Writer in Residence at Sunderland Polytechnic (1981-3) and he won a Cholmondeley Award in 1978. His collection Diplopic (1983) won the inaugural Dylan Thomas Award. Stet (1986) won the Whitbread Poetry Award and he was awarded the Lannan Award for Poetry in 1990 and again in 2004. In 1997 he held the Creative Writing Fellowship at the University of East Anglia. The collection Marfan (2000) was inspired by his tenure as Lannan Foundation Writer in Residence in Marfa, Texas, in 1999.

His third volume of collected poems - Collected Poems Volume 3: 1997-2003 - was published in 2003. His last poetry collection was Vendage Tardive (2010).

Peter Reading died in November 2011.

Critical perspective

Peter Reading was a highly original poet - his style was innovative and experimental, while his blunt outspoken tone and ‘grotty’ subject matter proved controversial.

He was also incredibly prolific - from the mid-1970s, he produced almost one volume per year. His deeply compassionate and humanistic concern for the suffering of individuals and the decline of modern society (as he saw it) was expressed in his poetry with fiery and passionate outrage, black humour and irony. He was not afraid to offer candid, grotesque and shocking images of the worst recesses of society, and his outraged concern for human suffering was combined with despair at humankind’s capacity for self-destruction.

Reading had a remarkable ability to combine compassion with detachment. As such, he was able to write about acute and heart-rending suffering (such as his collection, C (1984), about a man dying from cancer), without emotional over-involvement or sentimentality. He was an observer of human nature and society - insightful, sensitive, and profoundly concerned for the downtrodden - yet one who maintained a certain distance. Reading’s work also conveys intense anger and pessimism, holding out little hope for modern society, and he had no qualms about confronting his readers quite explicitly with life’s horrors, both those that are natural and unavoidable, such as illness and death, and those that are caused by the ignorance and vices of people and society, such as greed, violence, corruption, pollution:

'[…] And there’s pus in the weir; where once a white cumulus frothof cauliflowers boiled, there’s a fetid and curdling slackof turpentine slick clotting up with each new pollutantin a piled scum of rainbow blown corrugated and poxed […]'

(Extract from ‘Removals’ in For the Municipality’s Elderly (1974), which was Reading’s first full-length collection).

Reading’s technical skills are quite ingenious. One of the most frequent comments made about his work is the way in which he combines classical metres and formal structures with crude, vernacular language and raw and vulgar subject-matter. He plays with traditional forms and metres in such a way that his work sometimes goes beyond the bounds of conventional definitions of ‘poetry’. Isabel Martin defends Reading’s work against criticisms of his innovative style:

'[…] the term “poetry” as it is still widely understood is perhaps not large enough to encompass his art, and it is thanks to writers such as Reading, and the publishers prepared to print their work, that contemporary perceptions of poetry are gradually gaining a broader base.'

(Introduction to Reading’s Collected Poems Volume 1: 1970-1984, 1995)

Many of Reading’s collections, at least up to the 1990s, are each based around a particular theme (for example, death, mental illness, violence, homelessness) and there are many cross-references between individual poems (and between collections). Each collection is thus unified and self-contained, while Reading’s work as a whole is incredibly rich, complex and intense in both style and content. Robert Potts, who interviewed Reading for Oxford Poetry Magazine (Vol. V.3) comments that throughout the 1980s Reading’s collections often ‘dispensed with individually titled poems, standing instead as “novels in verse”: cross-referenced, polyphonic studies of human life from cosmic, global and individual perspectives’.

One of Reading’s most experimental and successful collections is C (1984), a collection of 100 prose pieces, each 100 words long, exploring the final period of a cancer-stricken man’s life. Though there is a rather scathing entry in The Oxford Companion to 20th-Century Poetry in English (1994), which describes C as Reading’s ‘least effective’ work, most critics disagree: Hugh Buckingham, writing in 1991, defines it as one of Reading’s best works (Reading entry in Contemporary Poets, 1991), while Isabel Martin, the foremost scholar of Reading’s work, refers to C as his ‘masterpiece’ (Introduction to Collected Poems: Volume 1, reference above). C’s brutally graphic and candid depiction of both the physical horrors and emotional trauma of terminal illness is shocking, poignant and deeply moving. Reading also pre-empted those who may criticise his unconventional forms and structures:

'No verse is│adequate.││ Most of us │ in this wardwill not get│out again.││This poor sod│next to mewill be dead│in a month.││He is young│has not beenmarried long│is afraid ││(so am I, so am I).'

(Extract from C)

C, like most of Reading’s work, offers a no-nonsense, down-to-earth type of compassion, rather than a contemplation of philosophical or spiritual ideas. Reading’s poetry focuses very much on dealing with the here and now, rather than the ‘bigger picture’, but his concern for humanity is no less for this - on the contrary, it forces readers to pay attention to the suffering that is being experienced by individuals at the present time, and suggests - often forcefully and angrily - that immediate and practical action is required, rather than using such situations for indulging one’s own sentimental or philosophical feelings.

Reading’s collection titles range from the experimental 5x5x5x5x5 (1983) to the gentle-sounding Ukulele Music (1985) to the abrupt Final Demands (1988) and Shitheads (1990). Throughout, however, he continues his raging and outspoken despair at the state of modern society. His collections in the 1990s include Evagatory (1992), Eschatological (1996) and Work in Regress (1997), and at this point he places less emphasis on having a singular theme for each collection. He also returns to individually titled poems. In the mid-1990s, Bloodaxe began publishing Reading’s Collected Poems in several volumes: Volume 1: 1970-1984 was published in 1995, and contains a useful introduction by Isabel Martin, who has also written the substantial and comprehensive study, Reading Peter Reading (Bloodaxe, 2000). It was followed by Volume 2: 1985-1996 in 1996. In 2003, Volume 3: 1997-2003 was published. Robert Potts’ review of Volume 3 (‘Repeat to Fade’, The Guardian, 13 December 2003) offers a useful overview of Reading’s career. He notes that, in Reading’s poetry as a whole, the flashes of insight and positive feeling are all the more illuminated against the general tone of bleakness: ‘[…] brief epiphanies and qualified sentimentalities were scarce enough to startle, and thus escaped “mawkishness”.’ However, Potts acknowledges that Reading’s pessimism and tendency to reiterate subject-matter from earlier works does become a bit wearing: ‘[Reading] has undeniably begun to bang on a bit’ (reference above).

Since the 1990s, Reading continually suggested that he may stop writing. The title of Last Poems (1994), was a clear statement, yet it was by no means his last, for Reading continued to write prolifically. Marfan (2000) and Faunal (2002) were particularly acclaimed by critics. The first of these is about a year spent in a small Texan town on a grant from the Lannan Foundation, while Faunal, as the title suggests, focuses on animals and nature, as well as the usual outrage at humanity and society. The poems are as angry and pessimistic as ever, but Marfan and Faunal display a return to the lively satire and irony of the earlier works. Faunal even displays the occasional rare glimpse of romantic contemplation:

'And I’d say (if I entertainedsuch mawkish conceits) that on eachof these afflatious encountersmy soul ascended like thatSkylark I watched as I lay and dreamed through a summer morningin a sweet pasture in Shropshireon an upland when I was younger.'

(‘Afflatious’)

In 2006, Reading published -273.15, which also met with a positive critical response. David Wheatley acclaims Reading’s continual gloom and doom: ‘The marvellous thing about him is not that he’s a nihilist but that he’s the world’s worst nihilist […] Long may his savage indignation rage’ (Wheatley’s review of -273.15, The Guardian, 4 February 2006). Reading himself also responds to those who criticise his pessimism. In the past, he has defended himself by commenting that his material is real life, not something he has made up, and that he simply presents it as it is. In -273.15 he takes a slightly more mischievous tone: ‘For it is my Likinge / Mankind to anoye.’

Elizabeth O’Reilly, 2009