Biography

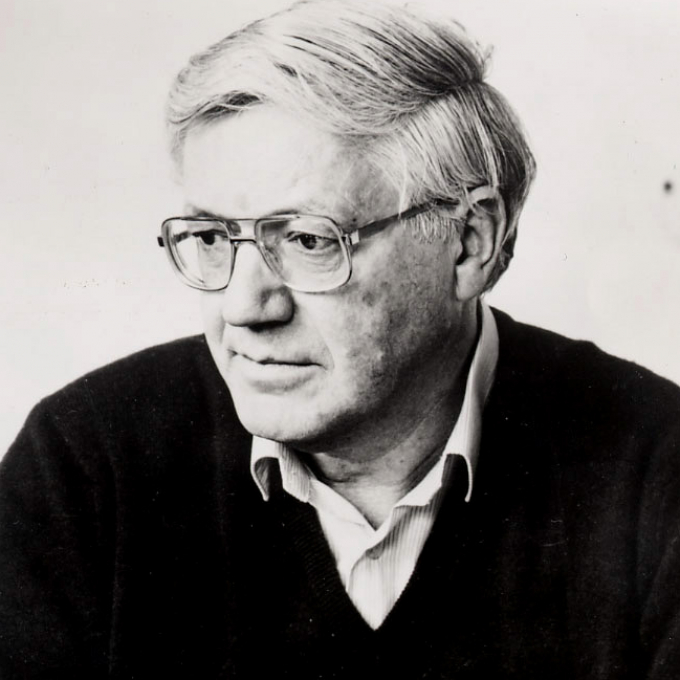

Poet Peter Porter was born in Brisbane, Australia in 1929.

He moved to London in 1951 and worked in bookselling and advertising before becoming a freelance writer and broadcaster in 1968, working for The Observer as poetry critic. During the 1950s he was associated with poets in 'The Group' (including Martin Bell and Philip Hobsbaum). In 2001 he was Poet in Residence at the Royal Albert Hall for the 'Proms' - a series of concerts given in London each year.

His first collection of poetry, Once Bitten, Twice Bitten, was published in 1961. The Cost of Seriousness (1978), regarded by many critics as his best work, was written after the death of his first wife in 1974. Collected Poems (1983) won the Duff Cooper Prize and The Automatic Oracle (1987) won the Whitbread Poetry Award in 1988. He was awarded the Gold Medal for Australian Literature in 1990.

Peter Porter's collection of poems, Max is Missing, was published in 2001 and won the 2002 Forward Poetry Prize (Best Poetry Collection of the Year). In 2001, 50 years after leaving Australia, he returned to Melbourne for the premiere of The Voice of Love, a song cycle with words by Peter Porter and music by the British composer Nicholas Maw.

Peter Porter was awarded the 2002 Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. His collection Afterburner (2004), was shortlisted for the 2004 T. S. Eliot Prize and Better Than God (2009), was shortlisted for the 2009 Forward Poetry Prize (Best Poetry Collection of the Year).

Peter Porter died in April, 2010.

Critical perspective

Peter Porter's collection Better Than God (2009), proved that his powers of inventive cultural conversation remained undiminished.

‘The Apprentice’s Sorcerer’ begins by discussing what the Geneva experiment in particle physics may tell us about the Big Bang: ‘Such hubris and such cost! What is there still / To do to prove creation’s codicil?’ But the subject quickly becomes a more familiar one for Porter’s readers: writers and musicians (his favourites Charles Ives, Wallace Stevens, Pascal, Hopkins, the violinist Joseph Joachim) who are the ‘apprentices galore’ of creativity itself. He draws this general conclusion: ‘Each innovator served an inner voice / Superbly iterating sounds of Truth, / Some from a lifetime’s wisdom, some from youth, / And none believing they had any choice’. We can include Porter himself as an apprentice in this context – even though one of his poems called poetry ‘A Lying Art’. Certainly in his latter volumes, including the Forward Poetry Prize-winning Max is Missing (2001), he wrote from a lifetime’s wisdom.

Porter arrived in London from his native Australia in the mid-1950s and became involved with the writers of ‘The Group’. These included Philip Hobsbaum, Anthony Thwaite, Peter Redgrove, and Martin Bell whom he was particularly close to. He edited the latter’s Complete Poems (1988), observing that ‘Opera was to remain for him the art closest to poetry in its combination of humanism and irrational emotion’, a remark that applies equally to Porter. He made W.H. Auden a particular model for his own cultured discursiveness and flexible poetic formality, while also regularly deploying the dramatic monologue derived from Robert Browning. His subjects stemmed from an all-consuming interest in the art, music and literature of Europe and the USA, mixed with a vein of social satire. (Porter’s previous occupations in advertising and literary journalism ensured that his poems often featured satirical usages of current buzz-words). His Australian identity - reflected in early poems such as ‘Phar Lap in the Melbourne Museum’ about a famous racehorse – re-emerged in later volumes, especially in memorializing his family and ancestors.

In an interview with fellow expatriate Australian writer John Kinsella, to mark the publication of his Collected Poems (1999), Porter remarked that ‘I like poems of ingenuity, poems of skill, poems of cleverness, poems which use words in ways other than the Wordsworthian ‘voice of true feeling’. In other words, I like poems to have a kind of plot of their own over and above the kind of worthwhile feelings of the poets’. [www.johnkinsella.org] This is the case, starting from the poems in his first book, some of which were reprinted in Penguin Modern Poets (no.2, 1962), a volume that he shared with Kingsley Amis and Dom Moraes. ‘Soliloquy at Potsdam’, for example, brings us the voice of Frederick the Great of Prussia: ‘Who would be loved/ If he could be feared and hated, yet still/ Enjoy his lust, eat well and play the flute?’ The nuclear war satire ‘Your Attention Please’ remains one of Porter’s most-anthologized poems, taking the form of a warning of an impending nuclear attack couched in officialese: ‘Some of us may die./ Remember, statistically/ It is not likely to be you’.

Porter’s most heartfelt volume is The Cost of Seriousness (1978). A number of the poems within concern the death in 1974 of his much-loved first wife Jannice. More generally, they reflect upon the adequacy or otherwise of art to deal with personal tragedy and death. Poetry itself is seen as ‘The Lying Art’, in a poem that opens: ‘It is all rhetoric rich as wedding cake / and promising the same bleak tears’, and goes on in similarly bitter vein: ‘Real pain/ it aims for, but can only make gestures’. In ‘An Exequy’ (its title meaning a funeral rite), Porter movingly addresses his deceased wife directly and reviews their travels in Italy together. The strict use of rhyming couplets disciplines what might otherwise be ungoverned emotion, depicting troubled dreams and impossible-to-answer emotional conundrums. ‘No-one can say why hearts will break / And marriages are all opaque: / A map of loss, some posted cards, / The living house reduced to shards / The abstract hell of memory / The pointlessness of poetry’.

In a triumphant return to prominence with Max is Missing (2001), certain poems are still haunted by his wife’s death, notably ‘The Lost Watch’ and ‘The Kipling Donkeys’, the latter recalling a family visit to Kipling’s house Bateman’s and drawing parallels with Kipling’s own losses. But elsewhere Porter’s faith in poetry - and in love - are fully restored, while wryly admitting that ‘Love can behave like the Carthaginian / Army; that it rages Racine-wise / Through sensitive and unintending veins’ (‘A Lido for Lunaticks’). As well as Porter’s usual strolls through European culture, his favourites have stayed with him. ‘Scrawled on Auden’s Napkin’ brings us Wystan’s querulous post-lunch thoughts on religion and food: ‘we do/ Insist that for a species whose most holy / Act is swallowing its God a well-made / Omelette is a Christian deed’. Porter’s own faith remains not so much in religion as in language: ‘Unlike our bodies which decay, / words, first and last, have come to stay’ (‘Last Words’).

Throughout Porter’s most recent volumes, Australia returned to him as a setting for meditations on family and national history. This is particularly striking in Better Than God. Its opening poem, ‘Buried Abroad’, refers to his father’s only brother, killed in the First World War, ‘with no known grave in France’. Yet a poem towards the end details his granddaughters finding and photographing the headstone in a Flanders Cemetery. ‘I was given Neville in his memory’, it observes, ‘I joined the House / Of Names years after he had left it – not words, not vows, / Just the invoiced pain’. This sense of Porter reconciling himself to Australia includes several vignettes of his father, who was one of ‘those who stay at home’ and cultivate garden flowers: ‘So Europe and Australia grew together in the sun / of his waterless Eden’ (‘Ranunculus Which My Father Called a Poppy’). Porter even summons up his Great-Grandfather, architect of the Boggo Road Gaol - subsequently filled with striking miners - to jokingly ‘help me to refuse / To praise my country’.

Reviewing yet another book on Auden, Porter once remarked that ‘a great poet must put all his mind into the poetry he writes’ [Poetry Review, Winter 1993]. This is what Porter himself did, prolifically, and in his own endlessly allusive manner.

Dr Jules Smith, 2009