- ©

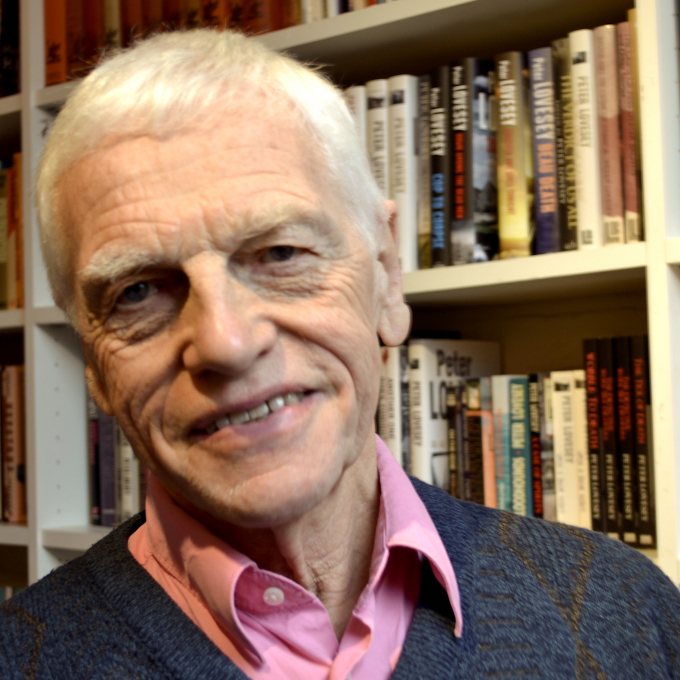

- Phil Lovesey

Peter Lovesey

Biography

Peter Lovesey (born 1936) is a prolific writer of historical and traditional crime fiction. He read English at Reading University, where he also met his future wife and literary collaborator, Jax Lewis. After National Service, where he became an RAF education officer, he taught English for fourteen years, in Essex and London.

Lovesey came to crime writing via his interest in sport. His first published book had been The Kings of Distance, about the lives of five long-distance runners. When, in 1969, Harper Collins advertised a prize of £1000 for a first crime novel, Lovesey immediately turned to his earlier research as the background. The result was Wobble to Death, a crime story set in the world of Victorian long distance walking races that were popular in the late nineteenth century. This was the first in a series of books based on sport and other entertainment in the Victorian age. When it was televised by ITV, he shared the writing of the scripts for the second series with his wife Jax.

In 1977 Lovesey started a second line of books, writing as Peter Lear. The first of these also drew on his background in sport. Golden Girl is about a brilliant young American runner, who aims to win three Gold Medals at the Moscow Olympics. Two other Peter Lear books followed: Spider Girl and The Secret of Spandau.

The novel that is arguably Lovesey’s best known appeared in 1982 - The False Inspector Dew, which was largely inspired by the Crippen case. This won the CWA Gold Dagger. Another stand-alone, On the Edge (1989), was later filmed as Dead Gorgeous.

In 1987, Lovesey began a new series of books, featuring Bertie, Prince of Wales, as the Detective. The first, Bertie and the Tinman, returned him both to sport and the Victorian era, based around the death of the jockey Fred Archer.

The Last Detective (1991) opened Lovesey’s Peter Diamond series, set in modern day Bath (though Diamond himself is anything but modern day). There are now seventeen books in the series.

Lovesey has also written many short stories and has continued to produce books on athletics, including a history of the Amateur Athletic Association on its hundredth anniversary.

Peter Lovesey is now arguably the doyen of British Crime writers. Canadian crime writer Louise Penny summed it up very well in her foreword to a new edition of The Last Detective: Lovesey is ‘a creative, courageous and gifted writer, who is also a gracious, generous and kind man. A gentle-man.’

Critical perspective

Peter Lovesey’s fiction falls into the categories of the traditional police procedural and historical crime fiction. He has said that the classic whodunnit, with a limited range of suspects, has ‘never been bettered as the structure for a mystery. That’s why it’s lasted so long. Almost every crime story works towards a final unravelling and the whodunnit makes the process into an art form.’

That said, his writing shows exceptional inventiveness and variety. Though he expresses great respect for the conventions of traditional crime fiction, he is not afraid to innovate or to break the rules. Indeed, he has compared the whodunnit to the string quartet - with a tight form but capable of infinite variation.

Lovesey’s first work of fiction, Wobble to Death (1970) is set in Victorian London, where race-walking, or 'wobbles', were all the rage. Lovesey had discovered these exhausting long distance races while researching an article in the newspaper archive at Colindale. He was interested to discover that the competitors would revert to all sorts of tricks, including taking tiny amounts of strychnine as a stimulant. The book opens on a Monday morning in November 1879, as the crowds gather in Islington's Agricultural Hall for a bizarre six-day endurance walking race. But by Tuesday, one of the contestants is dead. Tetanus from a blister is assumed, but then there is a second death amongst the contestants. A bemused Sergeant Cribb from Scotland Yard is called in, along with Constable Thackeray, and they soon discover that something foul is at play. Len Deighton described the book as ‘the perfect example of totally original people in a convincing historical setting’.

Lovesey continued with Cribb for another seven books. It was an epoch in which he felt very much at home and for which he had some sympathy. He writes: ‘I knew the Victorian period well through my interest in the history of sport. I learned a lot about the attitudes of the people at the time, their little vanities and hypocrisies, as well as their ways of surviving in a class-ridden society’. Like many writers whose work is televised, Lovesey found that the TV series was an impediment to continuing with the books. The actor had replaced his own concept of the character.

Lovesey remained in the Victorian era for his Bertie, Prince of Wales series. The ‘Tinman’ of the first book, Bertie and the Tinman, was Fred Archer, a jockey who had ridden for the Prince of Wales and who committed suicide at the age of 29. Archer’s last words to his sister were: ‘Are they coming?’ This set up an intriguing conspiracy theory - who were ‘they’ and what did they want? A review described the book as ‘Dick Francis by gaslight’. Lovesey followed this up with Bertie and the Seven Bodies, a spoof of the Christie-esque country house mystery, in which a murder occurs every day of the week, with rhymes sent as clues. It came out the year of the Christie centenary, though not everyone seems to have made the connection at the time. The running joke is that Bertie is useless as a sleuth but has the power to call in Scotland Yard whenever he needs them, or keep them at arm’s length.

It is probably Lovesey’s Peter Diamond series that collectively marks his greatest achievement. The opening book,The Last Detective (1991) was originally conceived as a stand-alone novel. Like its unforeseen successors, it is set in and around the beautiful city of Bath. Louise Penny has described The Last Detective as ‘ a novel that changed the face of detective fiction … it broke every template, every tradition, every rule in the genre’. In fact many aspects of it, from the multiple points of view to the grumpy, discontented policeman are very much in one excellent tradition or another of crime fiction. But Diamond is a marvellous, ultimately unique creation. Lovesey says that he deliberately made Diamond a dinosaur, frustrated by everything modern in police work. He is (to quote a Wall Street Journal review) an ex-rugby player, ‘impatient with forensic delays, hostile to computers, determinedly uninterested in learning new tricks’. He considers himself the last true detective. He is a difficult colleague, informing one of his juniors: ‘You’ll soon learn. I’m not easy to work for. Whatever you do, it’s wrong.’ Inevitably, Diamond leaves the police at the end of the first book, but is later able to rejoin on his own terms. The Wall Street Journal adds: ‘Mr Lovesey is a wizard at mixing character driven comedy with realistic-to-grim suspense’. DCI Hen Mallin appears with Diamond in The House Sitter, and subsequently in two books of her own.

If Diamond is Lovesey’s greatest series, The False Inspector Dew is his finest single book. It won him considerable critical praise and the CWA Gold Dagger for the best crime novel of the year. The book stems from an interest in true crime, which in turn goes back to the time that the Lovesey family were bombed out of their house during the war; one of the first books that Peter Lovesey’s father brought home after the bombing was the Life of Sir Edward Marshall Hall, the great defence lawyer who had been involved in the 'Brides in the Bath' case. (The other book was Leslie Charteris’s Alias the Saint.) The False Inspector Dew was inspired by two real-life events: the Crippen case and by the murder of Gay Gibson aboard the Durban Castle in 1947. It has a clever plot that keeps the reader guessing up to and beyond the last page.

Mention must be made too of another non-series book: in On the Edge, two women (Rose and Antonia) bored with their humdrum existence after the responsibilities that they shouldered during the war, decide, each for her own reasons, to murder their husbands. It is an attempt to understand the motivation of people who kill - a theme that runs through many of Lovesey’s books. He says that he consulted his wife Jax a lot on the book, especially on the way that women talked to each other when men were not there.

Peter Lovesey is also a prolific writer of short stories, having produced a number of collections of his own and contributed to countless anthologies. He says: ‘You can take risks with short stories that you can’t with a novel.’ One of his most innovative pieces of writing is in fact a short story - 'Youdunnit' - in which the reader proves to be the murderer.

All of Lovesey’s work is stylish and witty. Everything he writes has the air of having been carefully considered. He comments: ‘For me the pleasure comes in putting down the words, finding the appropriate ways of saying things.’

Peter Lovesey is one of the finest living exponents of the traditional mystery novel, while at the same time being a talented innovator. His immense popularity amongst readers and fellow crime writers is well-deserved.

Len Tyler, 2018