- ©

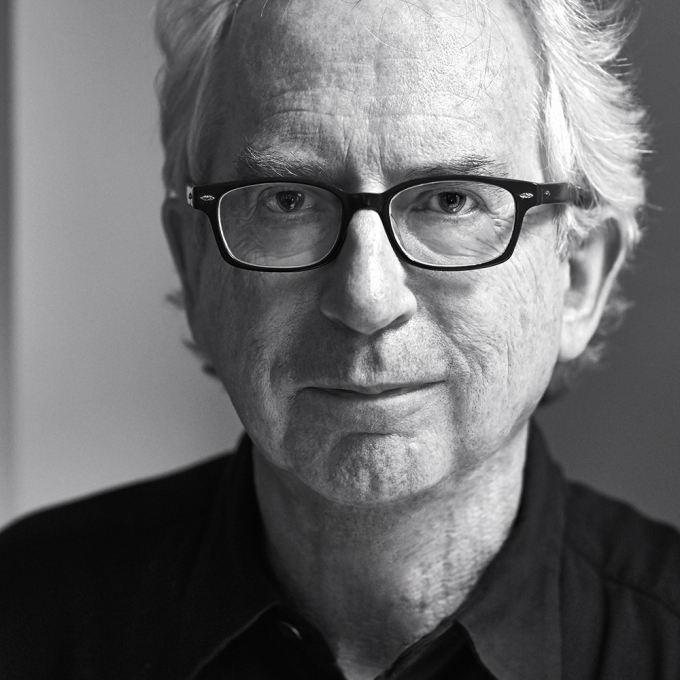

- Laura Wilson

Biography

Peter Carey was born in Bacchus Marsh in Victoria, Australia, in 1943.

He studied Science at Monash University, and wrote advertising copy to support himself during the early part of his literary career. Australian identity and historical context play a part in several of his literary works.

He began by writing surreal short stories, and published two collections, War Crimes (1979), and The Fat Man in History (1980). These stories, along with three previously uncollected works, are all included in his Collected Stories (1995).

He then wrote 3 novels: Bliss (1981), about an advertising executive who has an out-of-body experience; Illywhacker (1985), a huge vision of Australian history told through the memoirs of a 100-year old confidence man or "illywhacker"; and Oscar and Lucinda (1988), a complex symbolic tale of the arrival of Christianity in Australia. Although not a science fiction writer as such, there are some elements of this in his writing, particularly in Illywhacker, which led to this novel receiving the Ditmar Award for Best Australian Science Fiction Novel and being shortlisted for the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel, both in 1986. Illywhacker was also shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1985, and three years later, Oscar and Lucinda won the same prize.

While writing his next novel, The Tax Inspector (1991), Peter Carey moved to New York, and has since written further novels: The Unusual Life of Tristran Smith (1994); Jack Maggs (1997), billed as a re-imagining of Charles Dickens' Great Expectations; True History of the Kelly Gang (2001), told in fictional letters from the Australian outlaw and folk hero Ned Kelly to his estranged daughter; and My Life as a Fake (2003), a story centred around a literary hoax which gripped Australia in the 1940s. Jack Maggs and True History of the Kelly Gang both won the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Overall Winner, Best Book) and with True History of the Kelly Gang, Peter Carey won the Booker Prize for Fiction for the second time, in 2001.

Peter Carey wrote the script for the Wim Wenders film, Until the End of the World (1992), and co-wrote with Ray Lawrence, the screenplay for the film adaptation of Bliss (1985). Oscar and Lucinda was also adapted for film in 1997, with a screenplay witten by Laura Jones. He has also written a children's book, The Big Bazoohley (1995) and a non-fiction book, 30 Days in Sydney: A Wildly Distorted Account (2001). Wrong about Japan (2005), is a memoir/travelogue of the author's journey through Japan with his son Charley and their attempts to understand the Japanese culture and heritage.

Peter Carey still lives in New York, where he teaches Creative Writing at New York University. He has been awarded three honorary degrees and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the Australian Academy of Humanities and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His later novels are Theft: A Love Story (2006); and His Illegal Self (2008).

His novel, Parrot and Olivier in America, was published in 2010 and shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers Prize (South East Asia and South Pacific region, Best Book) and the Man Booker Prize for Fiction. His latest novel is The Chemistry of Tears (2012), which tells the story of a clock expert who is restoring an automaton while grieving for her lost lover.

Peter Carey was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia for distinguished services to literature, in 2012.

Critical perspective

During the epic course of Oscar and Lucinda (1988), Peter Carey’s postmodernist ‘Victorian’ novel, a clergyman transports a glass church across the desert as a ‘crazed image’ of his love for Lucinda, who in turn looks out at the ‘silver skin’ of Sydney Harbour: ‘A cormorant broke the surface, like an improbable idea tearing the membrane between dreams and life’.

The fabulous fiction of Australia’s best-known author internationally contains an abundance of such ‘improbable’ ideas and exotic scenarios, an endless inventiveness of storytelling within books that typically play games with narrative, chronology – and Australian history. They freely mix historical and fictional characters, the everyday with nightmares, and bring us Australian voices such as Herbert Badgery, the supposed 139-year-old narrator of Illywhacker (1985), and bushranger Ned Kelly whose ‘found journals’ constitute True History of the Kelly Gang (2001). Tall tales, lies and hoaxes are integral to Carey’s work, most exuberantly in Illywhacker but also in his novel, My Life as a Fake (2003), which draws upon a real-life Australian literary hoax of the 1940s, as an invented character comes to life with consequences for his creator both comical and murderous.

Carey was part of a generation of Austraslian writers who moved away from realism towards international models; by his own account he was first influenced by William Faulkner and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. His work’s hybrid mixing of fable, satire and fantasy can now be seen as akin to post-colonial novelists such as Salman Rushdie, Timothy Mo and Michael Ondaatje. What gives it distinction, though, is the distorting mirror it holds up to Australia, telling surreal stories about its development and place in the contemporary world, as in the political fable at the heart of The Unusual Life of Tristran Smith (1994), which takes place in ‘Efica’ and ‘Voorstand’ (Australia and America, and their love-hate cultural relationship). Tristan, the book’s deformed but theatrical narrator, is one of a number of ‘odd bods’ in Carey’s fiction, disguising his grotesque appearance by wearing a mask and a Disneyland-like costume to become ‘the enigmatic figure of Bruder Mouse’. Carey began by writing quirky short stories, such as ‘Conversations with Unicorns’ and ‘Report on the Shadow Industry’, while others have the offbeat sexual scenarios that recur in his work. In ‘Peeling’, for example, a woman is made to strip off, revealing several identities and changes of sex underneath, ending up as ‘a small doll, hairless, eyeless, and white from head to toe’. ‘He Found Her in Late Summer’ is also memorable, as a man finds that the beautiful woman he has rescued is a vampire.

Carey’s first novel, Bliss (1981), is an unnerving black comedy full of farcical episodes, the story of an advertising executive who, after nearly dying, realizes that ‘there were many different worlds, layer upon layer … and that if he might taste bliss he would not be immune to terror’. Harry Joy becomes convinced he is in Hell, surrounded by ‘all the cast of tormentors’. He finally abandons suburban morality himself by taking up with Honey Barbara, a hotel hooker, and he ends up on a Commune, talking to the trees. Bliss set a pattern in its satirical views of capitalism, sex and politics. Its fluid treatment of time is also characteristic: we wait until the final sentences to learn that the story is being told to us by Harry and Honey Barbara’s children.

‘Illywhacker’ is Australian slang for a trickster or conman. It is an apt title for Carey’s most purely enjoyable book, a cornucopia of incidents and characters unfolding over 500 pages, ‘a salesman’s view’ of Australian history related by Herbert Badgery, who advises at the outset: ‘I am a terrible liar … relax and enjoy the show’. Herbert tells about his life as a pioneer aviator, would-be businessman and drifter, being seduced by his future wife, 15-year-old Phoebe, while repairing her family’s roof. The action moves back and forth in time: Herbert as a child is taught to disappear and how to fight dragons by a Chinese magician, and during the Depression years goes on the road with his family, performing their ‘snake trick’ in hotel bars. During the war, he sets up a pet shop with American backing, supplying a talking cockatoo to General McArthur: a symbolic gesture within a book with a strongly satirical view of Australia. It ends with Herbert being kept as an exhibit, and, in a pointed contemporary note, the ‘best pet shop in the world’ is taken over by a Japanese corporation.

Like Oscar and Lucinda, Jack Maggs (1997) is a postmodernist pastiche of the Victorian novel, re-writing Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, specifically the relationship between Pip and the convict Magwitch. It is also a wonderful yarn about trickery and disguise. Jack Maggs, formerly a convict in New South Wales, has returned at great risk to 1837 London to see adoptive ‘son’ Henry Phipps and becomes entangled with rising young author Titus Oates. Mesmerised by Oates, Maggs tells his own story of criminality and lost love, and through his writer’s habit of collecting ‘characters’ Oates is himself (literally) captured by Maggs, and has to undergo his own love tragedy. True History of the Kelly Gang (2001) brings us another Australian telling his life-story. Or rather, many stories, set down in the idiomatic voice contained in ‘thirteen parcels of stained and dog-eared papers, every one of them in Ned Kelly’s distinctive hand’. He tells of his mother’s struggles to keep the family together, his criminal apprenticeship with bushranger Harry Power, and the truth about the murders at Stringybark Creek. Along the way we meet some idiosyncratic characters; a transvestite cowboy (‘Steve entered the hut like the Dame in the pantomime’), the love of his life Mary, a cast of corrupt policemen and authorities – and hear Kelly’s pleas to posterity for ‘the injustice we poor Irish suffered in this present age’.

My Life as a Fake (2003) has comic moments, and atrocities; once again the action moves around in time and the narrator may not be trustworthy. Sarah, previously editor of The Modern Review, tells us about events in 1972 when she was in Malaysia with veteran author John Slater, and their meeting with down-at-heel Christopher Chubb, once a young poet who invented the ‘Bob McCorkle’ hoax of the mid-1940s. Chubb’s own horror story takes over: he says that his adopted daughter was snatched by a madman claiming to be Bob McCorkle himself. Sarah plans to obtain Chubb’s own stolen manuscript (entitled My Life as a Fake), and her own secrets start to emerge. As a typically tricky tale in which readers and characters are never certain who is telling the truth, just who is hoaxing whom, the novel is quintessential Peter Carey.

Dr Jules Smith, 2004