Biography

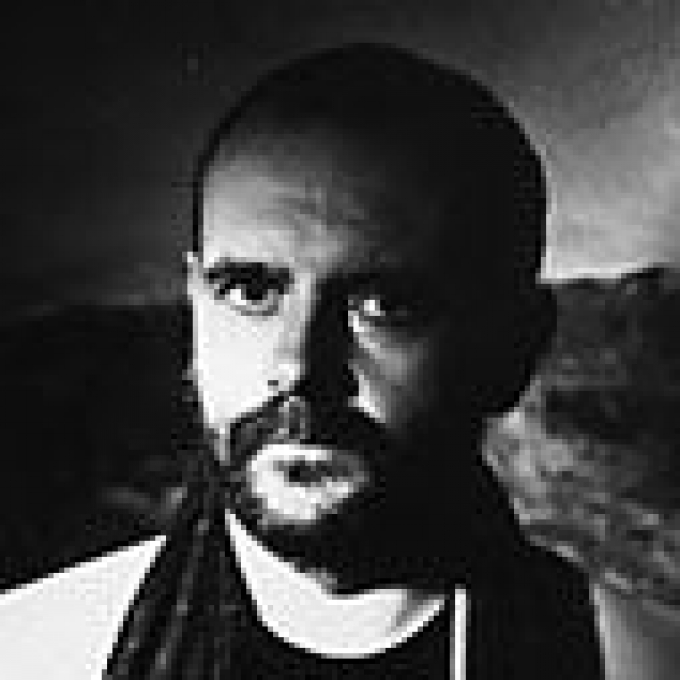

Playwright and novelist Patrick McCabe was born in 1955 in Clones, County Monaghan, Ireland. He was educated at St Patrick's Training College in Dublin and began teaching at Kingsbury Day Special School in London in 1980.

His short story 'The Call' won the Irish Press Hennessy Award. He is the author of several novels, including The Butcher Boy (1992), a black comedy narrated by a disturbed young slaughterhouse worker, which won the Irish Times Irish Literature Prize for Fiction; The Dead School (1995), an account of the misfortunes that befall two Dublin teachers; and Breakfast on Pluto (1998), the disturbing tale of a transvestite prostitute who becomes involved with Republican terrorists. The Butcher Boy and Breakfast on Pluto were both shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction. His novel, Emerald Germs of Ireland (2001), is a black comedy featuring matricide Pat McNab and his attempts to fend off nosy neighbours. Winterwood was published in 2006, and was named the 2007 Hughes & Hughes/Irish Independent Irish Novel of the Year. His latest novels are The Holy City (2008) and The Stray Sod Country (2010).

He is also the author of a children's book, The Adventures of Shay Mouse (1985), and a collection of linked short stories, Mondo Desperado, published in 1999. His play Frank Pig Says Hello, which he adapted from The Butcher Boy, was first performed at the Dublin Theatre Festival in 1992. The play is published in Far from the Land: Contemporary Irish Plays (1998), edited by John Fairleigh. A film adaptation of The Butcher Boy directed by Neil Jordan was first screened in 1996. His short stories have been published in the Irish Times and the Cork Examiner and his work has been broadcast by RTÉ in Ireland and the BBC.

Patrick McCabe lives in Sligo in Ireland with his wife and two daughters.

Critical perspective

Patrick McCabe’s leading protagonists all have certain things in common. They are all extraordinary people in very ordinary places – socially unacceptable, or at the very least marginalised. They are psychopaths and murderers and kidnappers and the like. But they are also engaging, often sympathetic (in the rather odd, sinister way that a psychopathic murderous kidnapper can be sympathetic) and very funny. For all their actions might shock and repel us, they’re surprisingly good company.

The award-winning The Butcher Boy (1992), McCabe’s most remarkable book to date, is a case in point. It tells the story of Francie Brady, a lively schoolboy in small-town Ireland (his home the home of so many McCabe characters). He is quick-witted and appealing; and this marvellous lad leads us merrily through the course of the novel, and we watch as he slowly approaches the brutal acts of the last pages (acts perpetrated by our young friend Francie himself), and we find ourselves quite suddenly face to face with the horrific violence with which all McCabe’s novels are tainted. Not for nothing did one critic describe him as 'a sort of high priest of rural Irish dementia'. Francie Brady’s voice is one of the most virtuosic pieces of first-person narrative-writing in many years; it is the power of this voice, its energy, its distinctiveness and irresistible charm, that drives the narrative along with such vigour. It shifts from the sharpest humour to the darkest horror, back and forth – terribly realistic and totally compelling throughout. A reader is left confused, dazzled and breathless. It’s astonishing.

The Dead School (1995) is less known than The Butcher Boy, but like this great predecessor it is an excellent and striking book. It is the story of two lives, two men of different generations whose paths cross, resulting in the destruction of both. The separate stories can be a little baffling at first, but once we have come to know the characters – and especially as the stories begin to intertwine – it’s captivating. The whole of the first half of The Dead School is pervaded with a powerful sense of optimism; and you’d be forgiven for believing that this optimism is unassailable, but of course knowing McCabe we know that it is only there to prepare characters and reader alike for an even greater fall. We know, by now, what to expect: everything will break down – relationships, reputations, sanities, all will disintegrate. And indeed the ending is almost unbearably bleak. 'And what a sad end it turned out to be …' And yet no worse than his other books …

Carn (1989) begins with similar optimism. The first few chapters show us the happy rebirth of a small town which has despaired of ever being prosperous again. Those who people Carn aspire collectively to make their town the great place it once was, and with some success: before long 'It seemed as if the town of Carn, … a huddled clump of windswept grey buildings split in two by a muddied main street, had somehow been spirited away and supplanted by a thriving, bustling place which bore no resemblance whatever to it.' The main character is the town itself, and like any McCabe hero Carn is allowed to be built up, filled with confidence and enthusiasm and optimism – why? Why, to tear everything down again, of course …

It would be misleading, however, to give the impression that McCabe is in any way a miserable or depressing writer. His world is prone to nastiness, certainly, and teetering on the edge of total, wild desperation, but it’s never hopelessly, lifelessly miserable. On the contrary his writing bursts with life (as do his characters), with irrepressible wit and energy. It is simply that the places he looks to for his humour are grim and unconventional – so the humour is mixed in with a view of the most shocking and disturbing elements of human weakness and cruelty. More often than not the result is a book which can appal, and yet with a personality which renders readers quite powerless to resist. At their best, these books are unstoppable.

McCabe’s most recent book, Call Me the Breeze (2003), is set in the border town of Scotsfield. Here unusually the principal character, hapless, lovesick, young writer-to-be Joey Tallon, does move (via kidnappings, prison sentences, border violence etc.) towards a sort of redemption and success; but the small-town setting is just the same as we’ve come to expect from a McCabe novel, the pervasiveness of the brutality is chillingly familiar, and we cannot but recognise something familiar in the dynamism of the main protagonist’s voice. Joey’s fantasies are all mixed in with the rest of the narrative to create something that is always shifting, unsettling and fractured (lots of little fragments rather than long chapters), always drawing attention to the form itself – indeed as much as anything this is a book about the importance of writing.

Further unsettling the already unsettled reader is the awareness through the book of the border troubles against which backdrop it is set. But like Carn and Breakfast on Pluto (1998), the Troubles are not merely a backdrop, but impinge (brutally, of course) on the main narrative and characters. These characters are not ciphers set in an abstract time, in an abstract (beautiful, rural, green, romanticised) Ireland, but people upon whom history and circumstance are acting, personally. And of course history and circumstance don’t treat them very well …

For books as steeped in violence as McCabe’s, it is worth noting that the reader doesn’t always see the blood and violence itself – we really don’t have to. But even when the violence is not described explicitly, the shadow of violence is present throughout – in the recent Emerald Germs of Ireland (2001), for instance, which is described on the dust-jacket as featuring Pat McNab 'in his post-matricide year'.

In 1998 McCabe was short-listed for the Booker Prize (for the second time, after The Butcher Boy) with Breakfast on Pluto – a book with many elements of vintage McCabe. It is the story of transvestite escort Patrick 'Pussy' Braden, who has escaped from Tyreelin and a drunk foster-mother to live in London, but finds her adopted city (the 1970s London of violence and squalour, the IRA threat and sex-for-sale at Piccadilly Circus) just as inhospitable in its way. Like Francie Brady, Pussy is damaged, but also like Francie she is full of strength as a character. That strength, the determination to be herself against the odds, in the face of a rough world, ill luck, hostile societies and some repellent characters, pulls her through to the end of the book intact, witty and full of life. Much the same could be said about any book by Patrick McCabe.

Daniel Hahn, 2002