- ©

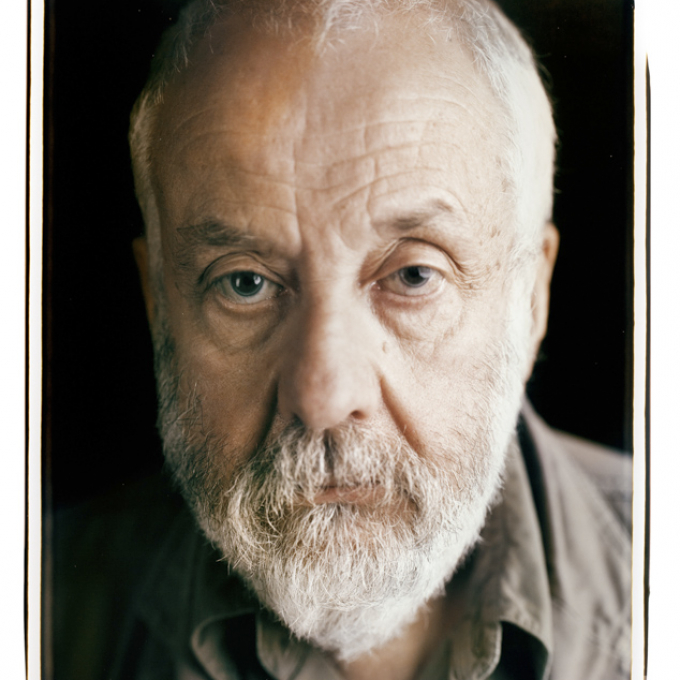

- Myrna Suarez

Biography

Mike Leigh is an award-winning screen-writer and playwright who was born in Salford, Lancashire, in 1943.

He trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and at Camberwell and Central Art Schools and the London Film School. He gained acting and directing experience with the Royal Shakespeare Company, and his first original play, Bleak Moments, evolved from improvisations. His career began as a playwright and theatre director, his stage plays including Smelling A Rat (1989), It's A Great Big Shame, Greek Tragedy, Goose-Pimples (1982), Ecstasy (1989) and Abigail's Party (1979), the latter being revived on its 25th anniversary and nominated for the 2002 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Revival. His latest plays are Two Thousand Years (2006) and Grief (2011).

Later he began to make films for television, then became involved with feature film production. His television plays, which he wrote and directed, include Nuts in May, Home Sweet Home, and Vera Drake. He is well-known for his films which do not begin with a script, but evolve from actors talking, improvising and creating characters. His multi-award winning films include All or Nothing (2002), Life is Sweet, Secrets and Lies (1997), Topsy Turvy (1999) and Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), which tells the story of Poppy, a cheery North London schoolteacher whose optimism exasperates others. His most recent films are Another Year (2010) and Mr Turner (2014).

Critical perspective

After training as an actor, Mike Leigh found himself drawn more to writing and directing, which is a relief, for if he had remained a thespian there would have been no Secrets and Lies, (1997) no Life is Sweet (1990), and no Abigail’s Party (1979).

Regularly compared to fellow filmmaker Ken Loach, Leigh shares Loach’s concern with everyday life and the dramatic conflicts that underlie it, but, with the marked exception of Naked (1994) and Meantime, two films which place their protagonists in defiant opposition to the society they find themselves in, Leigh is less political. Loach is a campaigning artist; his characters serve some purpose beyond the simple telling of a story. In contrast, Mike Leigh focuses almost wholly on character itself, illuminating the incidents and accidents and calamities of work, love and relationships; there is rarely the sense that they are serving as spokespeople for a cause.

There are some who deny that Leigh is actually a writer at all. Since his early days in the theatre at the Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham, he has developed his work in close collaboration with his actors. Instead of writing a script, Leigh works from a basic premise, however vague it may be, that will be fleshed out through months of improvisation and rehearsal. This will involve an exploration of the actor’s own experiences and people they know, things which will then inform the characters they develop; Leigh’s work then, is devised, so much of the credit must be given to those he works with. Equally significant is the way Leigh controls story: 'You have to be free as an actor from knowing what your character wouldn’t know.' Yet while his performers are vital to the process, it is Leigh, who moulds and shapes the work, who provides the simple instructions which allow the narrative to develop. The material is continually reshaped until the very moment the cameras role. It is then that the work is in some way 'fixed'. After that, there is little time for improvisation.

With the exception of his Gilbert and Sullivan biopic, Topsy-Turvy (1999), Leigh sets his stories amid the urban decay of the inner city, or amid the soulessness of suburbia, reminding all who watch that there is a world away from the country village stereotype of cricket lawns and quaint pubs serving warm beer. Given that Leigh delights in the work of William Hogarth, the 18th-century British painter, noted for his mocking of contemporary politics and customs, this is perhaps no surprise. Leigh has also cited Beckett and Pinter as influences, and one can certainly see them in his work, in the tragi-comedy, the use of silence, the regular appearance of one or more characters who seem aware of the absurd pointlessness of what they do, yet know they are compelled like a mouse on its wheel to do it again and again and again.

It is Leigh’s respect for character which makes him a vital artist. Inspired by the likes of E.M. Forster, 'because he deals with his characters both passionately and dispassionately; the character is always at the centre, but there’s always a high degree of objectivity as well,' Leigh has been responsible for some of the most notable creations in modern British cinema and theatre. The two which stand out above all others are Beverly in Abigail’s Party, and Johnny in Naked. Abigail’s Party, a comedy of lower middle-class tastes, began life in the theatre, before being made for television. Beverly has invited the new neighbours, Tony and Angela, over for drinks. Sue, her divorced neighbour, also comes along to get away from the party her daughter Abigail is having in their house. Beverly spends much of the evening engaged in snide argument with her husband Lawrence. Little happens; the comedy is derived from the mocking of affectation rather than any specific events; Lawrence, at one point, puts a Shakespeare play back on the bookshelf and says, 'our nation's culture. Not something you can actually read of course.' Beverly, monstrously grotesque and pretentious, was originally brought to life by Alison Steadman, an actress to whom Leigh was married for 25 years. She is shrill and full of superficial extravagance, masking an emptiness beneath, a hollowness at the heart of her fuelled by drink and role-playing. Seen by some critics as a savage dismissal of suburbia, Abigail’s Party does nothing but distort reality; that is the point, and it is done so effectively that it is extremely uncomfortable to watch.

The character of Johnny in Naked, memorably played by David Thewlis, generated great controversy. Leigh had to counter charges of misogyny upon the film’s release. 'The serious, mature feminist position has no problems with the film at all,' he said in a recent interview with The Guardian. 'I would argue that, whilst in no way, obviously, does one condone any kind of rape, every situation that’s shown is of people who are there by choice, for whatever sad reasons.' Egotistical, violent and utterly cold at heart, the unemployed Johnny, whose journey into a post-Thatcher wasteland in Naked is one of the most compelling pieces of modern cinema, is as attractive as he is repellent, blessed as he is with a charming wit and an intelligence you cannot help but fall under the spell of. He reminds me of Burgess’ Alex in A Clockwork Orange, there is a sense, paradoxically, in which he is actually the most sympathetic of the piece, despite what he does to others.

In its relentless misery, All or Nothing (2002), marks one of the few moments in Leigh when his work tips into caricature of itself. Everyone is so downtrodden, so self-centred or self-absorbed, so incapable of doing anything to improve their lot, that it all becomes too much. Despite its reasonably positive conclusion it is too little to late. Naked may be bleak, brutal and dripping with a relentless cynicism, yet it is intelligent, philosophical and possesses a standout protagonist. Leigh must guard against falling into self-parody, something it is all too easy to do in the latter stage of an artistic career.

Routinely criticised for patronising his characters, Leigh was, until his breakout film Secrets and Lies, more well-known and appreciated in France than in Britain. He has never won over the critics in his home country. There are always dissenting voices. Some even claim that Leigh exploits his actors by getting them to do the work for them. In a discussion with film critic Derek Malcolm Leigh responded to this, 'all art is a synthesis of improvisation and order. You discover what it is by interacting with the canvas or the page or the musical manuscript paper or whatever it is.' The actors are his tools then, his words, his notes on the stave. And it must be said that he offers them the opportunity to bring far more to their role than any other director currently working.

Like Woody Allen, Mike Leigh is a born pessimist; if you dismiss his work for being overly gloomy, it is probably because you prefer lighter, more optimistic reflections of the human drama.

Garan Holcombe, 2005