Biography

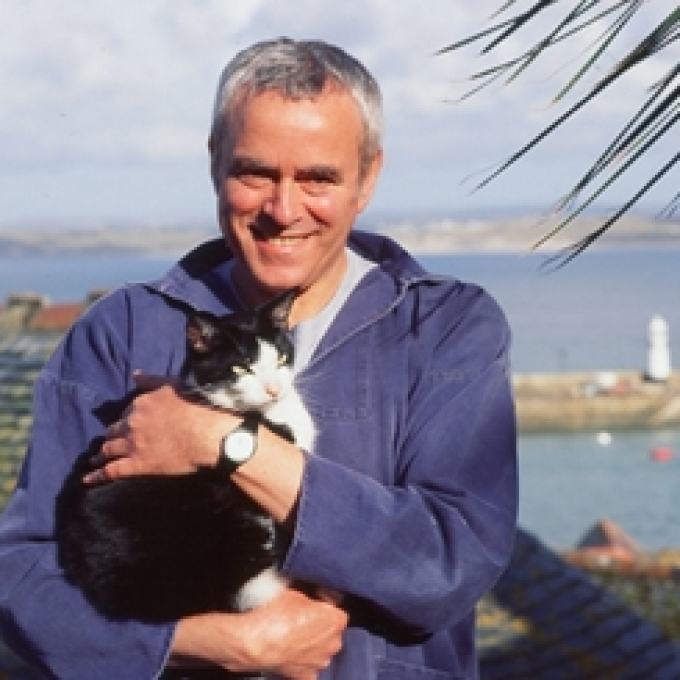

Michael Foreman was born in Suffolk in 1938 and grew up near Lowestoft.

He studied at Lowestoft Art School, and at St Martin's School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London. His first children's book was published while he was still a student.

After completing his studies, he travelled all over the world, making films and television commercials and doing hundreds of sketches which he later used as the inspiration for many of his books. Before becoming a full-time author and illustrator, he lectured at various Schools of Art.

He has illustrated books by authors such as Dickens, Shakespeare, The Brothers Grimm, Roald Dahl and Rudyard Kipling, has designed Christmas stamps for the Post Office, and regularly contributes illustrations to American and European magazines.

Michael Foreman also writes and illustrates his own books. He enjoys writing about earlier periods of history, including conflict and war, in books such as War Boy: A Country Childhood (1989), War Game (1993), and After The War Was Over (1995). The latter is about the soldiers of the First World War, was shortlisted for a Kate Greenaway Medal and won the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award 6-8 years category and overall winner) in 1993. His latest books are The Littlest Dinosaur's Big Adventure (2009), A Child's Garden: A Story of Hope (2009), Why the Animals Came to Town (2010) and The Tortoise and the Soldier (2015).

He has twice been nominated for the biennial, international Hans Christian Andersen Award for his contribution as a children's illlustrator, first in 1988 and again in 2010.

Many of Michael Foreman's books also feature Cornwall, where he lives when not in London.

Critical perspective

Michael Foreman’s sumptuously colourful picture books for children convey a sense of innocent play, appealing to the child’s own developing senses of adventure, wonder and imagination.

Journeying often provides the structure and imagery. In Hello World (2003), for instance, a bear in dungarees and a small boy go off ‘to see the world’ hand-in-hand, and are followed by kittens, puppies, ducks and other animals. They end up at night sitting on a hill, looking at the stars and moon (which looks back at them). The bear’s face, when first seen in white early morning light, looks very much like ‘Rupert Bear’. Nor might this be a coincidence: as Foreman explains in his memoir After the War was Over (1995), ‘I grew up on a diet of comics and magazines. As my mother ran the village shop, we sold almost everything, including Sunday newspapers …. [and] We had the … Daily Express because I liked to copy Rupert’. Such safe fabulous adventures may have provided an imaginative basis for the world created in Foreman’s art, albeit that in War Boy: A Country Childhood (1989) Foreman also describes a more earthy reality, as he and his friends explored bomb sites, the newly-liberated local beaches, and played games of Cowboys and Indians: ‘We were savages, chasing rabbits with knobbly sticks’. But his work often returns to issues of war, the environment, and above all a child’s need for freedom and adventure.

Over the past 40 years, Michael Foreman has become one of the best-known British writer-illustrators internationally, with more than 300 titles for both adults and children. He has enjoyed a long-standing involvement with the London-based literary magazine Ambit, and (a rather shorter spell) as an art director for Playboy. He is a superb colourist, typically covering the paper with luminous water-colour washes; blue seems his favourite colour, though greens, yellows, reds and pinks are used to equally great effect. He is skilled at suggesting vast skies and open spaces, and extraordinary panoramas, as in his Cat and Canary (1984) in which we see the skyscrapers of New York from the perspective of a cat riding a kite. Foreman’s style is especially suited to fables, folk and fairy tales, adept at suggesting menace, mystery, and the luminescent world of dreams. His Hans Andersen tales appeared in 1976, and his illustrations for Angela Carter’s Sleeping Beauty and Other Favourite Fairy Tales (1982), have many memorable images. We see Blubeard’s wife discovering a room full of skulls, a bad-tempered prince transformed by a fairy into a lion-headed amalgam of creatures; Beauty and the Beast; ogres, witches and fairy castles. Michael Foreman’s World of Fairy Tales (1990) collects tales from a variety of cultures, with his own location drawings.

Other highlights of his oeuvre include Leon Garfield’s Shakespeare Stories (in two volumes, 1985 and 1994) showing dramatic scenes in colour plates and black and white free studies in line and wash; they succeed in conveying a range of moods and atmosphere, from the ghostly haunting of Hamlet’s Elsinore to the moonlit mischief of Titania, Bottom and Puck. Clever visual detailing abounds, as in Much Ado, with Benedick shown hiding behind an ear-shaped bush. The murder of Julius Caesar has a naked figure in agony, with orange blood and knives sticking out. In The Winter’s Tale jealous King Leontes is shown in sickly green between Polixenes and Hermione.

Foreman lives and works for part of each year at St. Ives in Cornwall, a frequently used setting, as in Ann Turnbull’s The Sand Horse (1989), in which a sand drawing on St. Ives beach emerges miraculously to join the rough sea’s white horses. Foreman appears as himself, a local artist, in Saving Sindbad (2001), a dog’s eye view of the town, as it helps the crew of the St. Ives lifeboat carry out a rescue. Foreman is also a world traveller, and many of his sketches find their way into his work. For Kipling’s Just-So Stories he visited India to steep himself in the country; the pictures suggest The East in their red, pink and even orange light. World locations, and his concern for the environment, are prominent in his ‘Panda’ series: in Panda and the Bushfire (1986), his friend the winged lion rescues koalas during a fire in the Australian outback. Watercolour sketchbook extracts decorate his football tale Wonder Goal (2002), showing children playing football all round the world, from New York to the Tibetan border, Italy, Egypt and a schoolyard in China, united by their love of the game.

Foreman is a fine autobiographer. His memoir, War Boy: a Country Childhood, combines photographs and even adverts alongside his water-colours and pen-and-ink drawings. Amid wartime and food rationing, the influx of foreign servicemen, life goes on at his mother’s shop in the Suffolk village of Pakefield. It opens dramatically, a fire-bomb coming through the roof of the room where he is sleeping, a two-page picture illustrating the air raid: ‘the sky bounced as my mother ran … the sky flared red as the church exploded’. He records with simplicity and humour the impact of the arrival of the Americans; embarrassments with the outside lavatory; his first encounters with movies and bananas. Part of the appeal is that the adult artist is constantly negotiating with his childhood self, and it ends with a haunting image of the landscape, ‘the ghosts of us children in the fields and woods of long ago’. After the War was Over opens in the Summer of 1945, with victory bonfires, as the beach was cleared of mines and a wrecked landing craft ‘became our pirate ship’. Its theme is that of the boy growing up into the artist. The art college he attended was traditional, and he learned that ‘painting the same person over and over … teaches you about seeing and reading colour. I had no idea there were so many pinks, blues, yellows, ochres and mauves in flesh’. For War Game (1993), Foreman re-imagined the First World War, and its Christmas Truce scenes in the trenches (‘No Man’s Land’) re-appear in Michael Foreman’s Christmas Treasury (1999).

In complete contrast are exuberant works such as Michael Foreman’s Nursery Rhymes (1991). Alongside traditional rhymes are riddles, lullabies, nonsense verse, tongue twisters, and amusing pictures: cats in coats decorated with fish, a ship crewed by mice, with a duck captain. There are intriguing links from one rhyme to the next. ‘Mary, Mary, How Does Your Garden Grow?’ is joined by characters from other rhymes, and ‘The Grand Old Duke of York’ goes up one side of a hill while Jack and Jill come tumbling down the other. Michael Foreman’s Playtime Rhymes (2002) is a delightful companion volume, containing over seventy exuberant ‘action rhymes’, and a cast of animals, who dance round the mulberry bush, walk through the jungle and go to the fair, do the hokey-cokey and join the Teddy Bears’ picnic. We see an elephant in a sailor suit, or walking along a spider’s web. Iona Opie, in her introduction to the Nursery Rhymes, rightly called Foreman an artist ‘who possesses his own spyglass to look into the furthest corners of the old nursery dramas, finding possibilities and consequences never imagined before’.

Dr Jules Smith, 2004

Bibliography

Awards

Author statement

He comes from the same wide skies and melting sunsets as the greatest of his fellow water colourists, John Sell Cotman, Peter de Wint and J M W Turner. But, unlike them, he paints more than landscapes. Michael Foreman paints dreams.

You will find his gentle tones and vibrant colours in bookshop windows, on classroom shelves, in a million children's bedrooms up and down the landscape and in dozens of lands too!

He can take us to the soaring mountains of New Zealand in his Maori tales (Land of the Long White Cloud), or to the ghastly wilderness of the No Man's Land of the First World War (War Game).

Somehow he brings us close, draws us into his pictures, involves us. His range, breadth and depth, are extraordinary, his interpretation breathtaking.

Michael Morpurgo