- ©

- Natasha Billington

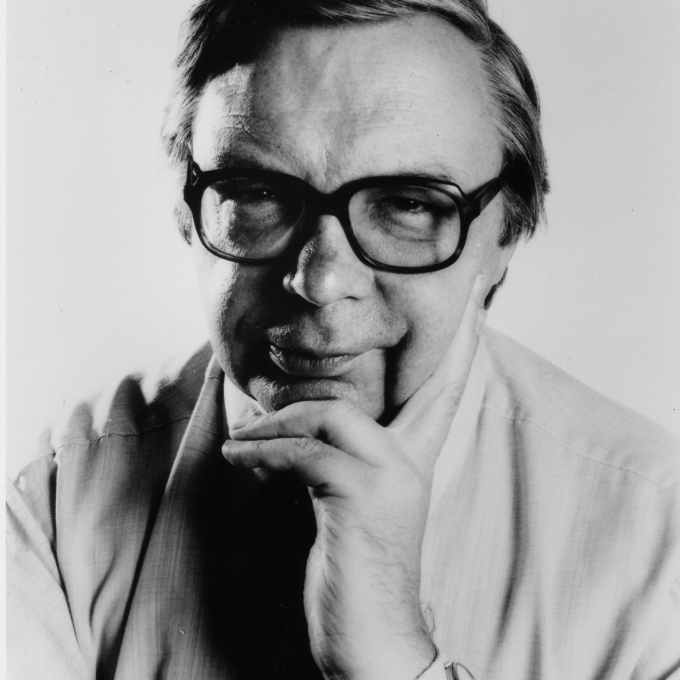

Michael Billington

- Leamington Spa, England

Biography

Theatre critic Michael Billington was born on the 16 November 1939 in Leamington Spa. He was educated at St Catherine's College, Oxford, and began working as a journalist in Liverpool. He worked as Public Liaison Officer and Director for Lincoln Theatre Company (1962-4) and began reviewing films, plays and television programmes for The Times in 1965. He became film critic for the Birmingham Post and the Illustrated London News in 1968.

He has been the drama critic of The Guardian newspaper since 1971, is drama critic for Country Life magazine and has written frequently for the New York Times. He is a regular contributor to radio and television programmes and was a former presenter of the BBC Radio 4 arts programmes Kaleidoscope and Critics' Forum. His books include biographies of the playwrights Tom Stoppard, Alan Ayckbourn and Harold Pinter.

One Night Stands: A Critic's View of Modern British Theatre (1993, re-issued 2001) is a collection of his reviews for The Guardian. He has also edited Stage and Screen Lives (2001), a collection of biographies of personalities from the film and theatre worlds written for the Dictionary of National Biography.

Michael Billington lives in London. His latest book is 101 Greatest Plays: From Antiquity to Present (2015).

Critical perspective

"Criticism, to me, is not the last word: simply part of a permanent debate about the nature of the ideal theatre", Michael Billington stated in One Night Stands: A Critic’s View of Modern British Theatre (1993).

Having written for The Guardian since 1971, he can fairly claim to be Britain’s longest-serving theatre critic; he began as a student in the late 1950s, becoming deputy to Irving Wardle on The Times from 1965-71. His writing is informed by a vast fund of knowledge about the art form, from five decades of witnessing landmark productions and great performers. In the introduction to his book, State of the Nation: British Theatre since 1945 (2007), he estimates that he has had "around eight thousand nights sitting in theatres". What distinguishes his criticism over the years has been his constant urging of writers and directors towards engaging with political and social themes. Yet, he is no dogmatist. On the contrary, his enthusiasm for virtuoso performers includes stand-up comedians; among his favourites being Ken Dodd – whose stage act he celebrated in How Tickled I Am (1977) - Max Wall, Ken Campbell, Dame Edna Everage, and Jack Benny. He also loves musicals, though Sondheim rather than Lloyd-Webber.

Billington has usually argued for the pre-eminence of the writer in theatre, but he is deeply appreciative of directors, designers, and what he calls the "mystery’ of the actor’s art", as is evident throughout his biographies of Peggy Ashcroft, Harold Pinter (for whom "acting was always a form of release") and Alan Ayckbourn. Indeed, by the conclusion of Peggy Ashcroft (1988), despite his long friendship with her and in-depth observation of her stage career, he admitted a "failure" in trying to solve her mystery: "Peggy commanded attention through a serenity that seemed to come from within". He did formulate the view that "so much acting is about cutting away the dead wood and finding the simplest, clearest, truest way of delivering a line". And – and this is a view he has repeatedly referred to – "My own belief is that as performers get older, acting becomes increasingly a judgement of character".

One Night Stands: A Critic’s View of Modern British Theatre, a selection from his Guardian reviews written between 1971 and 19991, prefaces each section with a summary of that year’s significant political events. The plays he sees in 1972, for instance, which include the Sondheim musical Company, take place in the context of a major political crisis in Northern Ireland. By 1973 he is reporting on "a change of direction at the National", with the handover of power to Peter Hall, and commending Olivier’s final "rock-like" stage role in Trevor Griffiths’ play The Party at the Old Vic. By October 1977, Billington’s open letter deplores "Britain’s Theatrical Chauvinism", but the same year notes that the RSC has "struck gold" with Trevor Nunn. In 1982, he is watching the Cambridge Footlights revue and hailing the young talents of Emma Thompson, Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry ("who has the omniscient repose of a natural butler"). While initially approving the rise of musicals in the 1980s, such as Cats ("an exhilarating piece of total theatre"), he calls Starlight Express "Thatcherism in action". In 1989, he has a novel experience for a critic – directing a play by Marivaux, relishing "the spontaneous combustion of rehearsal". The final review, of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde by David Edgar, takes the form of a witty dialogue between the two characters: "He proves yet again that le vice anglais is adaptation".

The Life and Work of Harold Pinter (1996, revised edition 2007) cleverly opens with an account of interviewing the actor-playwright, observing that in Pinter’s plays "any conversation between two people conceals a tactical battle for advantage". Billington is particularly good in discussing the personal origins of Pinter’s psychological themes, such as betrayal, and sex as a battleground: "His stage plays are commonly triggered by a sharp memory of some personal experience which then develops according to its own internal logic". Billington has been an eyewitness to Pinter’s work virtually from the start, seeing The Birthday Party in 1958, works such as Betrayal (which he admits to misunderstanding) and the more recent politically resonant plays. His first-hand account of meetings with Pinter over the years greatly enlivens the book. Billington concludes that Pinter "has forged a direct connection between the private and public faces of power… which gives his work its universal resonance and ensures it a fretful immortality".

The premise of State of the Nation: British Theatre since 1945 (2007) concerns the relationship he sees between the theatre and society in Britain, from the Atlee government of 1945 to the Blair Government of 1997. He began with "an insatiable curiosity about the extent to which theatre was influenced by the political temper of the times and about the way it may even have propelled social change". It is necessarily a highly personal view but also draws valuably on his recollections of classic productions of the past and modern revivals. The basic division in post-war theatre, he argues, was between the Idealists (notably Olivier or Joan Littlewood) and the Pragmatists (traditionalists such as producer Binkie Beaumont). Another valuable aspect of the book is its extended discussions of neglected seminal playwrights such as John Whiting and Ann Jellicoe (whose work anticipated Sarah Kane and Mark Ravenhill). He also re-assesses Terence Rattigan, and the usual view of Noel Coward as a stylishly apolitical writer, calling the latter "a sentimental reactionary petrified of change".

Billington recalls attending the revival of Look Back in Anger during August 1957, naively standing on the steps of the Royal Court "and watching people coming out of the first-house Saturday performance to see if they had been visibly changed by the experience". But he did see the first performances of Beyond the Fringe at the Edinburgh Festival "and [I] remember coming away not just aching with laughter but sensing that the ground had genuinely shifted". Billington has been a staunch supporter of Sir Peter Hall, who he calls "the single most influential figure in post-war British theatre". The final section, ‘1997-2006 New Labour, New Theatre?’ discusses the rise of factual or ‘verbatim theatre’, dramatising the trials and enquiries during the Blair government. For Billington, "the glory of theatre" still lies in the prospect of an encounter with "a visionary intelligence or an enquiring mind". His own commitment to "the state of the nation play", as written by George Bernard Shaw, J.B. Priestley, Howard Brenton or David Hare, has been consistent. He continues to express his indefatigable enthusiasm for the theatre in all its varied forms.

Dr Jules Smith, 2008