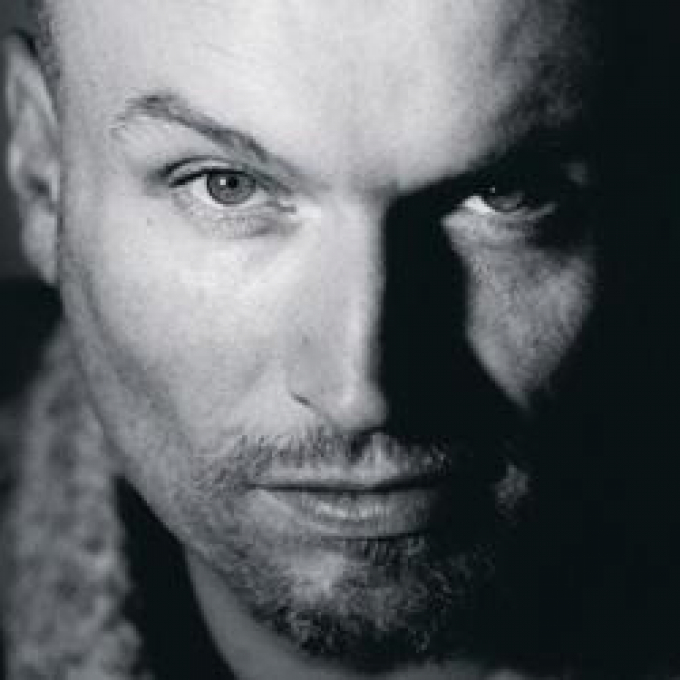

Mark Ravenhill

- Hayward's Heath, England

Biography

Playwright Mark Ravenhill was educated at Bristol University where he studied English and Drama, and worked for the Soho Poly in London.

His first piece, a ten-minute dialogue called Fist, was staged at London's Finborough pub theatre venue. Max Stafford-Clark, director of Out of Joint Theatre Company, saw the production and invited Ravenhill to contribute a full-length play. This became Shopping and Fucking, produced by Out Of Joint Theatre Company, opening at the Royal Court Theare, London, in September 1996.

His next play, Faust Is Dead, was produced by the Actor's Touring Company and toured nationally in 1997. It was followed by Handbag in 1998, which won an Evening Standard award, and Some Explicit Polaroids, which opened at the Ambassadors Theatre, London, in November 1999. In 1998, while literary director of Paines Plough, a company started in 1974 to develop new writing, he organised 'Sleeping Around', a collaborative writing project.

Mother Clap's Molly House, set in 18th-century London, was first performed in 2001 at the National's Lyttleton Theatre with music by Matthew Scott. His radio play Feed Me was broadcast by BBC Radio 3 in 2000. Totally Over You (2004), is a play which explores the world of instant celebrity. In 2006, four further plays were published: The Cut and Product; and Citizenship and pool (no water).

Mark Ravenhill lives in North London. His latest play to be published is Over There (2009).

Critical perspective

In a once expensive but now shabby flat, a man and a woman attempt to feed an ill friend. He cannot eat and instead vomits violently in front of his two friends. This happens in the first minute of Mark Ravenhill’s first play and acts as a statement of intent for the often-visceral theatre that makes up the rest of his oeuvre. The vomiting character, also called Mark, is typical of Ravenhill’s characters – a drug addict, sexually ambiguous and promiscuous, a piece of human urban driftwood. Even without emptying his stomach, Mark is not the sort of figure to please the average middle-class London theatergoer. The offense is deliberate and starts long before the first scene of Ravenhill’s first play, Shopping and Fucking (1996). Offending the audience starts, of course, with the title of that play, which in publicity posters, on the marquee of the Royal Court Theatre where it premiered, and on the cover of Ravenhill’s collected plays (although not inside) it appeared and appears censored, as Shopping and F***ing. As with most censorship, the deletion of the offending matter only attracted more attention to what was missing and further contributed to the success of one of the most important theatrical events of the 1990s.

It is not for shock value alone that Ravenhill has his protagonist vomit on stage and places provocative words in his title. In fact, all his plays lead us towards the conclusion that the most shocking word and activity in the title of Shopping and Fucking is not the last one, but the one that goes uncensored, the seemingly banal, everyday one, ‘shopping’. The world of Ravenhill’s plays is the underside of our modern culture of conspicuous consumption, where happiness awaits at the end of a commodity, where the logic of the marketplace is invincible. Mark vomits, then, for a reason. Vomiting is the antithesis of consumption, an absolute rejection of the imperative to consume. That is not to say that Ravenhill’s characters are not consumers. They consume recklessly, excessively, badly: drugs, sex, the nineties culture of rave music. They are equally consumed themselves, consumed by passions and activities not endorsed by an official culture which constantly sells sex and actively solicits the ‘pink pound’, but baulks at sodomy and anulingus. In Shopping and Fucking, Robbie short circuits an economy based on buying and selling by extravagantly giving away some 500 ecstasy tablets (less the ones he takes himself) in a night club, an act which epitomizes the unconscious resistance to consumer culture found in Ravenhill’s plays.

This description almost makes Ravenhill sound like a political playwright, even though he rejects conventional political theatre. Speaking of one of the grand old men of British theatre, Ravenhill says, ‘(David) Hare and the rest knew in the Seventies what they were against. Now nobody knows and nobody cares.’ Certainly in Ravenhill’s first three full-length plays, Shopping and Fucking, Faust is Dead (1997) and Handbag (1998) there are few glimpses of a public sphere of politics beyond the solipsistic universes of the characters. In the seventies, left-wing playwrights such as David Edgar and Trevor Griffiths explored labour politics, dramatizing the worker’s relation to the place of production. By the nineties, however, the British economy had moved inexorably away from manufacturing and towards service industries: the Indonesian or Thai worker makes the Nike trainers or Gap jeans; the smiling British ‘worker’ simply sells (and of course buys) them. This transformation of Britain into a retail economy is reflected in Ravenhill’s plays, where his characters, if they do work, rarely produce or make anything. In Shopping and Fucking, Robbie works the till in an unnamed burger chain, Lulu tries to sell her image as a model, and Gary is a rentboy, selling himself as sex. In Handbag Suzanne and David work as market researchers, and in Faust is Dead, Donny is another rentboy while Pete appears to be the son of Bill Gates, the progenitor of a virtual empire.

In Ravenhill’s view, in a modern retail economy characterised by dispersal, there is no more factory floor where workers can find common cause. Instead, we find in his plays a concern for ‘micro-politics’, the finite local struggles championed by the French thinker Michel Foucault, who appears thinly disguised as Alain in Faust is Dead, waxing philosophical in the desert outside Los Angeles. In Handbag, meanwhile, the plot centres on the politics of fertility and care, as two couples, one gay, and the other lesbian, attempt to conceive and then care for a child. The baby, through the neglect of child-minders, dies. The play therefore acts out a common anxiety fantasy of affluent parents while pointing out the exploitation of inexperienced carers who bear the burden of nurturing the offspring of the wealthy. Handbag interweaves this modern tale with an imaginative prehistory of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, taking the perspective of the exploited Miss Prism, who was also a failed child-minder in her time.

Some Explicit Polaroids (1999), Ravenhill’s fourth and most accomplished play, is populated with the familiar gallery of criminals, junkies, sex-workers and psychotics who are Ravenhill’s heroes. It also ventures for the first time into the world of conventional politics, staging an encounter between the political nihilism of the late twentieth century and what Ravenhill perceives as the certainties of the seventies. These (socialist) certainties are represented by Nick, a leftist activist jailed in 1984 and only just released. The incompatibility of his strict Marxism with a modern Britain of retail and consumption provides the main fault-line of the play. He is particularly out of step with the changed sexual politics of Britain. First he attempts but fails to resume relations with his ex-girlfriend Helen, who has abandoned radical politics for reform, seeking a seat in Parliament. Then he embarks on a vexed relationship with the stripper Nadia, but is unable to cope with her ethereal disengagement from the world, her laissez faire attitude towards human relations. It is to Ravenhill’s credit that the condemnation of Nick’s masculine politics does not prevent him from casting an equally satirical gaze over the apathetic, de-politicised characters opposed to Nick.

This summary gives Some Explicit Polaroids more coherence than it aspires to. Its structure, like all Ravenhill’s plays, is episodic, loosely plotted rather than carefully crafted. In other words, these plays are like the title of the fourth one – a series of snapshots scattered across the stage, with the audience left to trace the connecting lines between the pictures. Sensation, in this dramaturgy, takes precedence over suspense. Indeed, Ravenhill’s plays are often remarked upon for showing what should not be shown: vomit, sexual acts, violence. Their theatricality, like that of Ravenhill’s now dead contemporary Sarah Kane, is one of shock, shock which is reinforced by the theatrical aesthetic of nightclubs – strobing effects, the sudden blast of dance music lurching spectators out of their chairs. However, what Ravenhill does not show the audience is often more powerful than these jarring but superficial effects. Just as in classical tragedy the most brutal scenes are left off-stage, only to be reported second hand, so Ravenhill as often as not has his characters tell harrowing stories during theatrically quiet moments. This use of narrative is illustrated in Shopping and Fucking when Lulu comes into the pub with blood on her face. She proceeds to tell Robbie of the murderous stabbing attack by a tramp on a Seven-Eleven clerk. What horrifies her most is not that she did nothing to help, but that she used the attack as an opportunity to steal a TV guide and a chocolate bar. The most hideous offense is not the failure to help a fellow human being, but the transgression against the rules of consumption most of us so automatically obey.

Dr. Peter Buse, 2003