- ©

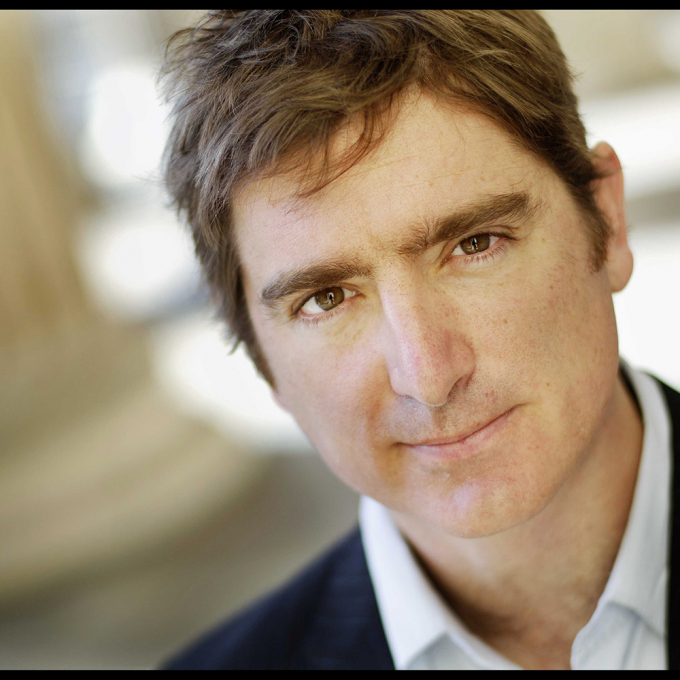

- Sarah Lee

Marcel Theroux

- Kampala, Uganda

Biography

Marcel Theroux is a screenwriter, a broadcaster and novelist. He is the son of travel writer Paul Theroux and brother of acclaimed film maker Louis Theroux.

He was born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1968. He grew up in England, was educated at Westminster School, before studying English Literature at Cambridge University and International Relations at Yale.

He has published five novels. His second novel, The Paperchase, won the Somerset Maugham Award. His fourth novel, Far North (2009) was a finalist for the U.S. National Book Award, the Arthur C Clarke Award, and was awarded the Prix de l’Inaperçu in 2011.

Far North has been translated into German, Dutch, and French. A Japanese edition prepared by the celebrated novelist Haruki Murakami was published in April 2012.

Theroux’s fifth novel, Strange Bodies, was published by Faber and Faber in the United Kingdom and Ireland in May 2013. It will be published in the US by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in February 2014.

In addition to his books, Theroux has written a number of original screenplays and written and presented more than a dozen documentaries on subjects ranging from climate change to the Japanese aesthetic principle of wabi-sabi.

Critical perspective

Over the course of five novels Marcel Theroux has developed a reputation as a distinctive writer of award winning, highly conceptual novels. Perhaps even more impressively, by doing so he has managed to escape the lingering pressures of that famous surname.

After some time searching for an appropriate mode or genre, Theroux has honed a particular type of novel of ideas whose conceits owe much to world of progressive speculative fiction. Whereas the most famous trait of his father Paul Theroux’s work was, as one reviewer has put it, “exploit his own life experiences, and those of the people close to him … Marcel seems to adopt a more distanced, conceptual bent.” (Sunday Herald, 2013).

Thanks to the prominence given to biological and technological themes in his works, Theroux has been dogged by perennial reductive questions over genre. Is his work ‘science fiction’? On this point, he has been quite eager to avoid pigeonholing, remarking that:

I was trying to be as free as possible. I don't really think about genre ... to be honest. I find it constraining. And I know there's a certain embarrassment about talking about science fiction in polite company, so some people prefer to call it "speculative fiction" instead. (NPR interview)

In being so untroubled by notions of genre, he points out that he is in good company. Murakami might be a good model, says Theroux: “He’s kind of freed things up for us. You know, Bulgakov – is he sci-fi? Is he magic realist? Even our own tradition, George Eliot, The Lifted Veil, that’s sci-fi, isn’t it?” But in reality, his route to his current mode has been anything but direct, and his previous novels demonstrate a range of uneven stabs at various genres.

His first novel was Stranger in the Earth (1999), a fish-out-of-water comedy set in a South London newsroom which, a picaresque tale of a country boy attempting to navigate the cynicism of the modern metropolis. It helped establish Theroux’s customary blend of wry low-key but didn’t suggest the more adventurous themes his later works would address. The New York Times saw promise in the work, especially for how it “narrates these events with authority and brio, fluently weaving small oddball nuggets of social detail into his story while tossing off some brightly observed cameo portraits along the way. Though his ending is a little rushed, though his humor is occasionally forced, he has written a charming and sprightly novel.”

It was his follow up, A Paper Chase (published as The Confessions of Mycroft Holmes in the US) in 2001 that began to make his reputation. This time the broad genre was mystery, as the story focused on jaded journalist Damien March and his transformation into an unwilling detective when a crumbling Cape Cod pile is bequeathed to him in his uncle’s will. The legacy states that the Victorian mansion must leave untouched, but Damien soon comes across letters and old manuscripts that reveal his uncle’s fascination with ‘Mycraft Holmes’, the elder brother of Sherlock. As Damien begins to dig deeper into his uncle’s imagination, the book begins to become a study of his hidden family resentments, and a literary through papers and documents develops into a study of ultimately violent personal rivalry.

It did not escape reviewers’ notice that its themes of familial competition might be at least partly autobiographical. But though the insight into the Theroux upbringing may have been the initial appeal, reviews applauded The Paperchase’s execution and conception. Reviewing the book for the New York Times, John Lanchester found “something very satisfying about the momentum of the novel. The story moves forward with a pleasant, unthrillerish pressure. The novel's other great delight is Damien's narration; Theroux extracts full value from his rootless, sceptical, sharp-eyed perspective.” James Urquhart in the Times of London praised “the author's deft descriptions of an angular childhood spiked with the soft humour of hindsight which remain in the mind. Theroux's restraint evokes the shimmering quality of memory, and the awareness that clear images crumble to dust with over handling”. The novel received the 2002 Somerset Maugham Prize.

Theroux followed this with the muted urban revenge comedy Blow to the Heart (2006), set in and around the world of amateur boxing. Its protagonist Daisy is a young journalist whose husband’s violent murder leads her to stalk his killer, whose boxing fixation she becomes involved in as part of her plans for revenge. Part of the pleasure of the novel was again the fish-out-water experience of the middle class female ingénue amidst the macho frenzies of ring and gym. Of that choice of setting, Theroux has spoken of how he became

intrigued by the whole idea that there were these guys who would turn up, get thumped round the ring, get paid and then go back to work on Monday morning on a building site,' he says. 'It seemed a desperate sort of life in a way, but there was also something oddly heroic about it.'

Reviews for this novel were generally positive. The Independent thought that the novel gave “old-school clichés a contemporary spin … A precise and fluent stylist, Theroux inhabits the boxing gym as unobtrusively as he does Daisy's more metropolitan world.” Writing in the Observer, Helen Zaltzmann concluded that “though the novel's focus is somewhat shifting, eventually deserting even Daisy herself, Theroux shows a remarkable gift for characterisation, from pain-racked Daisy to boxing promoters and realistic humour, even in the midst of intense bleakness.”

Far North (2009), his fourth book, was to be his most prominent to date. This post-apocalyptic novel focused the frontier of an imagined failed state destroyed by global warming, and the figure of (seemingly) lone survivor Makepeace Hatfield, whose isolation is suddenly punctured when she discovers that she may not, as she had feared, be the last citizen alive. After witnessing a plane crash, she comes into contact with other survivors, and endures enslavement amid the poisoned landscape of an obliterated civilization.

Though it owed more than a little to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Theroux managed to wring fresh life out of the formula of ‘last man’ or ‘end times’ literature. The ecological vision of the novel was widely praised. Lydia Millet in the Washington Post thought that “Far North may well be the first great cautionary fable of climate change.” But on the level of execution, opinions were more divided on whether Theroux truly transcended the cultural tropes of the post-nuclear genre. Tim Martin in The Telegraph found that his initial admiration of the novel began to slip as “the magic begins to fade in the second half of the book … Until about 40 pages from the end, Far North feels as though it’ll be the slightly bumpy first book of a promising trilogy: then Theroux begins channelling Stalker [the Tarkovsky sci fi film] and the book embarks on a headlong sprint to an unsatisfying finish.” Far North was shortlisted for the Arthur C. Clark Award, one of the most prestigious awards given for science fiction; it was also a finalist for the National Book Award, and has found a growing place on the school literature syllabus.

Theroux’s most recent novel, Strange Bodies, brought a similarly elaborate, high-concept approach to the issue of artificial life. Its deadpan opening, promising to tell the tale of “when Nicky Slopen came back from the dead,” sets the novel off as a mystery surrounding the unexplained re-appearance of a literary academic who was assumed dead, before it turns into a dark reflection on nanotechnology, Cold War bioscience and the prospect of consciousness in a post-human world. Mixing the playful intellectualism of Jorge Luis Borges, the speculative science fiction of Philip K. Dick, and a twist of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, this was a novel of ideas, a modern day Frankenstein. Speaking to NPR about his choice of subject, Theroux was explicit about placing Strange Bodies in this lineage:

It's interesting, every historical period, whatever is the cutting edge of science is the thing that seems to hold out the promise of living forever. So it's blood transfusions in the early part of the 20th century; it's electricity for Mary Shelley in Frankenstein; and now its nanotechnology and computing, that we'll turn into a hive of nanobots — we'll have our consciousnesses uploaded onto the Internet in some way that will preserve them forever. (NPR interview)

The political philosopher John Gray saw much to admire in the probing ambition of this post-human fable, lauding it as “an absorbing and disturbing metaphysical tale, challenging everything we believe about what it means to be human,” To Justine Jordan in the Guardian, “Strange Bodies couldn't be more different” from its post-apocalyptic predecessor, but exhibited the same capaciousness of imagination and sympathy … the notion that consciousness may be no more than "a trick of the light", is moving as well as thought-provoking, as elegiac as it is gripping.” For some, however this novel of ideas left them cold. Despite “all its laudable aims” wrote Steve Almond in the New York Times, “Theroux’s novel never made me feel deeply for Nicholas Slopen, or his experimental twin. And thus their saga, as Shelley puts it, “never presented itself to my mind with the force of reality.”

With five novels and a prolific presenting and journalistic career to his name, Marcel Theroux might be forgiven for having safely escaped the pressures of his last name. Understandably, he has long seen it as something of an albatross. Both he and his documentary-maker brother Louis, he laments, are too often seen as “franchises of Paul Theroux Limited,” not least by their competitive father. On this topic, Marcel is disarmingly frank:

When I started writing, I did have some idealised notion of my dad as a writer. But I have less and less of a literary rivalry with him as I've gone on. I certainly don't feel I need his approval, although maybe that's because I'm confident that I've got it. I'm quite sparing about how many of his books I read because I don't want to be over-influenced by him, but sometimes I still catch echoes of his stuff in what I write; it's as if it's there in the DNA.

As he has slowly but surely edged away from the family franchise, he established his own reputation as one of the more versatile British writers of his generation. And he has plenty of time yet to dispel any lingering qualms about his dynastic status. 'The great thing about being a novelist,' he has said, 'is that by the time you're 50 you can still be getting into your stride. I feel I'm still starting out, still finding my own voice.”

Dr Tom Wright