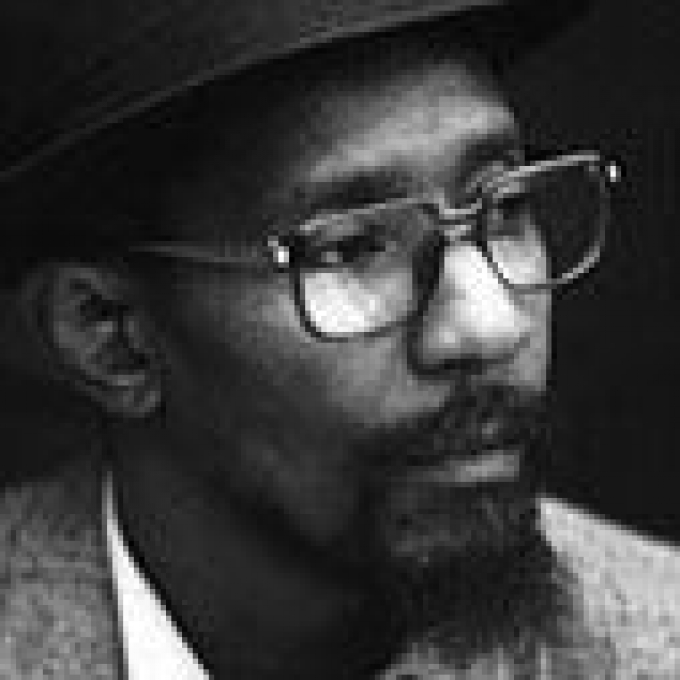

Biography

Linton Kwesi Johnson was born in 1952 in Chapelton, Jamaica. He moved to London in 1963 to be with his mother and went on to read Sociology at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He joined the Black Panther movement in 1970, organising a poetry workshop and working with Rasta Love, a group of poets and percussionists. He joined the Brixton-based Race Today Collective in 1974. His first book of poems, Voices of the Living and the Dead, was published by the Race Today imprint in 1974. His second book, Dread, Beat An' Blood (1975) includes poems written in Jamaican dialect, and was released as a record in 1978.

He is widely regarded as the father of 'dub poetry', a term he coined to describe the way a number of reggae DJs blended music and verse. Johnson maintains that his starting point and focus is poetry, composed before the music, and for this reason he considers the term 'dub poetry' misleading when applied to his own work. He recorded several albums on the Island label, including Forces of Victory (1979), Bass Culture (1980), LKJ In dub (1980) and Making History (1984) and founded his own record label - LKJ - in the mid-1980s, selling over two million records worldwide.

In 1977 he was awarded a C. Day Lewis Fellowship and became Writer in Residence for the London Borough of Lambeth. Race Today published his third book of poetry, Inglan Is a Bitch, in 1980. He worked primarily as a journalist in the 1980s and was a reporter for Channel 4 television's The Bandung File. Tings An' Times: Selected Poems was published in 1991 as both a book and musical recording.

He was made Associate Fellow at Warwick University in 1985 and Honorary Fellow at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in 1987. He is a regular broadcaster on radio and hosted an evening of Caribbean music and culture for BBC Radio 2 in October 2001.

Linton Kwesi Johnson lives in Brixton, South London. A selection of his poetry, entitled Mi Revalueshanary Fren, was published in 2002 as a Penguin Classic edition with an introduction by Fred D'Aguiar. In 2005 he was awarded a Musgrave medal by the Institute of Jamaica, for eminence in the field of poetry.

Critical perspective

Linton Kwesi-Johnson can be said to be the most significant Jamaican poet writing in the U.K. because his verse is read and appreciated widely and far beyond the community it is initially grounded in.

Yet, for such an influential contemporary voice, Kwesi-Johnson appears to have published little - a mere 5 collections since 1974. Numerical values aside, there can be no doubt that what has been published is of immense cultural importance. Publishing editors apparently concur as in 2002 he became the first black poet to have his Selected Poems (2006) published in the Penguin Classics series. In this series he joins a canonical grouping of British poets including Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare, Alfred Tennyson and perhaps most interestingly Rudyard Kipling who was damned by George Orwell as 'the prophet of British Imperialism' (Rudyard Kipling, 1942). His selection for this esteemed series is testament to the immediate and enduring power of his work both during the 30 years they address and to readers today.

On the page at least, the aspect that sets Kwesi-Johnson's work apart is the aggressively unpretentious lexicon, creating 'Sense Outta Nansense' (Tings An Times, 1991). For those familiar with the highly stylised English language of the most frequently anthologised poets, Kwesi-Johnson's expressive Jamaican Creole becomes evidently politicised as it tells 'a story nevvah told' ('Sense Outta Nansense'). Kwesi-Johnson is a poet writing against the grand (white) traditions by using the repressed language of Britain's Black working class. For some, it is the familiar dialect of their community, for others it can seem estranging and harsh. Yet, Kwesi-Johnson's skill does not discriminate, even the 'oppressin man' is welcome to 'hear what I say if yu can' ('All Wi Doin Is Defendin', Dread, Beat An' Blood, 1975) and the phonetically astute nature of the verse rewards articulation, reinforcing its roots in performance, people and protest.

Russell Banks in his introduction to Mi Revalueshanary Fren (2002) succinctly identifies Kwesi-Johnson's poems as works 'that make us sing with a voice that mingles our intimate own with a stranger's, the poet's intimate own ... we end up singing a people's song'. This musical element is an important part of Kwesi-Johnson's art; its reggae heritage lends rhythm, and even in some instances, theme. Music, like verse, offers the possibility of transcendent freedom in 'Bass Culture' when 'di beat will shif / as di culture alltah / when oppression scatah' (Dread, Beat An' Blood). The 'musik of blood / black reared' ('Bass Culture') is part of community, but it is one forced into resistance, at war with itself because of its subordinate class status and the many social problems that causes. The community described in 'Dread, Beat An' Blood' is one driven to violence by social misery, where 'a fist curled in anger reaches a her / then flash of a blade from another to a him / leaps out for a dig of a flesh of a piece of skin / an blood bitterness exploding fire wailing blood and bleeding' is the tragic physical response. Kwesi-Johnson's own verse compositions do not promote such bleak self-resentment; they provides a persuasive rallying call against apathy, stating that 'yu got to fite / fe yu rite / wid yu mite' before there can be 'peace' ('Song of Rising', Dread, Beat An' Blood).

Kwesi-Johnson's written work is one small part of his artistic output. He is recognised as the founding proponent of dub poetry, a form of stylized performance poetry, and is thus the forefather of many contemporary recording spoken word artists. Performance, whether actual or recorded, is a necessity for appreciation of his talent, and many CDs are available on his record label LKJ. Tings an Times, an album released to accompany his 1991 collection of the same name, blends the calm ebb of reggae tunes with the rage and despair of black consciousness in the divided Britain of the 1970s and 80s.

Contemporary readers who have not experienced the decades Kwesi-Johnson addresses may find his work self-consciously historical. His poetry forms a valuable chronicle of Black working class life and the social injustices prevalent at the time. For the uninitiated, his poems are helpfully classified in Mi Revalueshanary Friend as 'Seventies', 'Eighties' and 'Nineties Verse', although the socio-economic conditions are apparent in the poems without the need for in depth historical contexts – 'it was a night named Friday / when everyone was high on brew / or drew a pound or two worth a kally' evokes a scene more clearly than any timeline could aspire to demonstrate ('Five Nights of Bleeding', Dread, Beat An' Blood).

Kwesi-Johnson's political concerns are obviously of social injustices and racial inequality, but they are not often permitted to become such general terminology. 'Sonny's Lettah' (Inglan is a Bitch, 1980) tells a tale of police brutality, 'dem t'ump him... dem kick him in him seed', through a personal letter sent from 'Brixton Prison / Jebb Avenue / London SW2'. The cringing formality of the opening lines, 'I hope dat wen / deze few lines reach y'u / they may find y'u in di bes' af helt' meets with the ominous, and darkly humorous 'I really doan know how fi tell y'u dis'. The tragedy of Sonny's state of affairs marks him as a victim of a degenerate society that assaults him, then 'dem charge mi fi murdah'. 'Inglan is a Bitch', perhaps Kwesi-Johnson's best known poem, also has some humour in the telling. The speaker (and again we get a dispossessed speaker gaining voice through Kwesi-Johnson's verse) is endearingly preceptive about his exasperating situation. The speaker works night and day and still 'dem seh dat black man is very lazy', he finds that 'dem have work, work in abundant / yet still, dem mek me redundant' until all the hard working migrant can do is 'goh draw dole'.

What Kwesi-Johnson jokingly demeans as poetry 'wid mi riddim / wid mi rime / wid mi ruff base line / wid mi own sense of time' ('If I Woz A Tap-Natch Poet', Mi Revaleushanary Fren) is work of great artistic merit as part of the migrant poetic traditions gaining recognition in the later twentieth century. As social commentary, the work is a record of political reaction to repression when Black voices were simply not heard. As poetics and politics, this verse and its concerns show no signs of falling out of fashion. In so many senses, the questions it urges upon readers of every creed loom large and are as relevant today as they were when they were first penned.

Alex Pryce, 2009