- ©

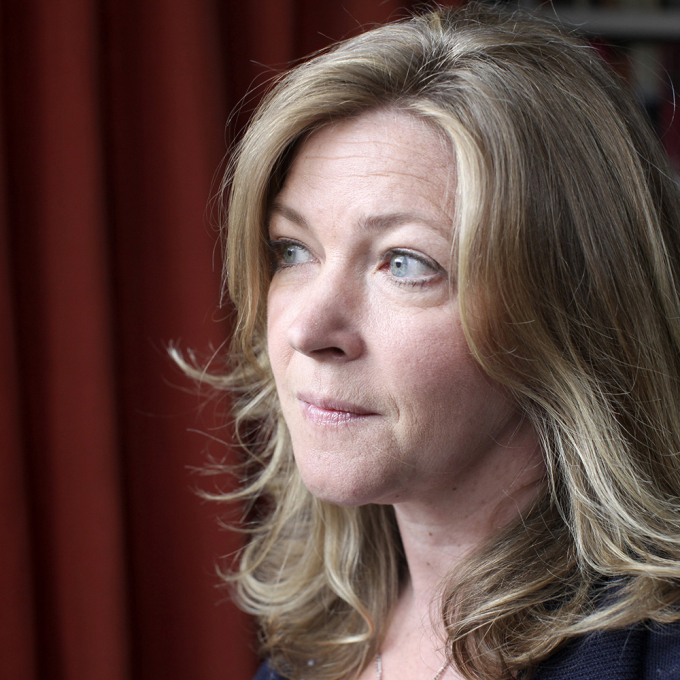

- Eamonn McCabe

Kate Summerscale

- London

Biography

Kate Summerscale was born in 1965 and brought up in Japan, England and Chile.

She studied at Oxford University and gained an MA in Journalism in the US. She has worked for The Independent and as literary editor of the Daily Telegraph, and her articles have been published in The Guardian, the Daily Telegraph and the Sunday Telegraph.

Her first book, The Queen of Whale Cay, the biography of 'Joe' Carstairs, was published in 1997. It won a Somerset Maugham Award and was shortlisted for the Whitbread Biography Award. It was followed by The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher: or the Murder at Road Hill House, a merging of research and storytelling about a notorious 1860 murder case. Mr. Whicher was one of eight policemen to join Scotland Yard's Detective Branch in 1842. It won the 2008 Samuel Johnson Prize and two British Book Awards in 2009.

In 2012, her third novel, Mrs Robinson's Disgrace: The Private Diary of a Victorian Lady was published. It tells the story of Isabella Robinson, a love affair and a highly public divorce. The Wicked Boy: An Infamous Murder in Victorian London was published in May 2016 and told the story of a shocking murder case in late Victorian Britain.

Kate Summerscale lives in London.

Critical perspective

Although it was The Suspicions of Mr Whicher (2008) that brought Kate Summerscale to widespread public notice, the former journalist’s first book, published just over a decade previously, did not want for critical acclaim.

The Queen of Whale Cay (1997) won a Somerset Maugham award and was shortlisted for the Whitbread Biography Award; it also marked a first foray into an area that Summerscale would subsequently make her own: the hybrid biography. Her territory is, as the critic Kathryn Hughes has succinctly put it, the 'throttled passions of Victorian family life', and her methods those of the novelist. But Summerscale’s oeuvre is grounded firmly in fact.

Whale Cay, as Summerscale explains in an introduction, began with a letter that she received in 1993 while working on the Daily Telegraph’s obituaries desk. It came from one Jane Harrison-Hall, suggesting that her late godmother, Marion Barbara Carstairs, might make a suitable subject for an obituary. As Summerscale discovered, Carstairs’ was an extraordinary story: born in 1900, she was 'a cross-dressing lesbian' who went by the name of Joe and attained fame as a champion speedboat-racer in the 1920s. The middle decades of Carstairs’ life were spent on an island in the Bahamas, which she bought with an inheritance, and while she was never short of lovers one of her closest relationships was with a foot-high leather doll named Lord Tod Wadley.

Though appreciative of its virtues, Summerscale did not feel that the obituary form was suited to the more complete portrait of Carstairs that she found herself wanting to paint. She also wished to write a book that 'connected Joe Carstairs to the century she spanned,' – although, as Terry Castle observed in the London Review of Books, Summerscale did not ultimately 'try to extract from Carstair’s life any larger cultural meaning or sociopolitical message.' Instead, 'What commentary [she] provides is understated and of a literary and mythopoetic cast - as if she were describing a character out of Ovid’s Metamorphoses or Perrault’s fairy tales.'

If Carstairs was a stranger-than-fiction figure, then it was in part the unexceptional character of the hero of The Suspicions of Mr Whicher that ensured his fictional afterlife was so eventful. Jack Whicher’s unobtrusive personality as much as his pioneering profession made him irresistible to novelists: he was, it seems, fiction waiting to be translated from the flesh.

The case at the dark heart of Summerscale’s hugely popular bestseller was the grotesque killing of three-year-old Saville Kent in Bath in 1860. Known as the Road Hill House murder, the crime was appalling enough to come to national notice and warrant investigation by Scotland Yard’s first detectives. Among them was Jonathan Whicher. As Summerscale writes, 'He was ordinary-looking, keen-sighted, sharp-witted, quiet.' And as Whicher was, so have fictional sleuths continued to be: he was a living, breathing blueprint.

Almost from the moment it was committed, the Road Hill House murder was providing inspiration for novelists. Wilkie Collin’s The Moonstone (1868), often cited as the first detective story, borrowed details from the case, while its hero, Sergeant Cuff, owed a debt to Whicher. Yet even in the twentieth century the long shadow of the killing persisted in such works as Other People’s Worlds by William Trevor (1980).

The case was clearly a gruesome gift for journalists and writers from across the spectrum, from contemporary hacks to household names. And yet, as Summerscale confessed to the Guardian’s Book Club, her initial attempts at telling the Road Hill House story 'fell flat'. It was only after interviewing the crime novelist PD James – Summerscale having left the Telegraph’s obituary’s desk to become its literary editor – that the solution presented itself. 'It struck me that the Road Hill murder was itself an archetype of the detective genre, and I decided to try writing my story in the form that it had helped inspire: the crime novel.'

Just as the Saville murder sparked what Wilkie Collins called a 'detective fever', the book that Summerscale subsequently produced triggered a frenzy of its own. The author had, Lisa Allardice of the Guardian noted, 'pulled off the publishing feat of becoming a brand – ‘in the tradition of Mr Whicher’ now appears on the back of other titles.'

It is interesting that one of very few criticisms of the book came from a novelist. The crime writer Ian Rankin, in a gently partisan review in the Guardian, described the book’s overall feel as that of 'dry, courtroom testimony', going on to conclude that although 'Summerscale is persuasive in tying the Road Hill House case to movements in crime fiction at the time… the murder itself lacks the intricacies and niceties of the novel.'

However, Summerscale has made it clear that she is not in the business of inventing where the facts fail to supply. Speaking to Lisa Allardice on the publication of her next book, Mrs Robinson’s Disgrace (2012), she suggested that it would be a 'sort of violation' to 'appropriate' real people and 'say what they felt when you don’t know'. This, however, is married to the awareness that a work will always bear the imprint of its author. 'I don’t tend to interpret the facts directly or give an overt opinion,' Summerscale told Publishers Weekly, 'but my interpretations are there in the shape, pattern, emphases, context that I give the story.'

In Mrs Robinson’s Disgrace, Summerscale again explicitly linked her historical material to contemporary fiction. The book’s subject, Isabella Robinson, was at the centre of one of the Victorian era’s most scandalous divorce cases; tried as an adulteress, her diary was read out in court as evidence against her. The journal was, writes Summerscale in her prologue, 'more godless and abandoned than anything in contemporary English fiction. In spirit, it resembled Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary'.

While some reviewers suggested that Summerscale did not entirely convince in connecting Flaubert’s fictional heroine to the very real Mrs Robinson, the book again received widespread critical praise on publication. In a nuanced review in the Guardian, Alexandra Harris did however note that 'Summerscale might have been more upfront about her own methods of narration in a book so concerned with reading, writing and the interpretation of documents… It comes as a surprise, for example, late in the day that Summerscale has not read Isabella’s diary, the fateful book having been lost or, more likely, destroyed.' Nonetheless, Summerscale’s mission to once again place Victorian society under the microscope was judged a success, paving the way for The Wicked Boy (2016).

As Kathryn Hughes observed in the Guardian, one notable feature of this book is that it reversed Summerscale’s previous pattern. The 'horrible act' upon which it focused – matricide, committed by a thirteen-year-old East End boy named Robert Coombes– 'wasn’t the prompt for a new kind of fiction, but its consequence.' Sensational penny dreadful books, or 'penny bloods', were held responsible by certain sectors of the press for inspiring Coombes in his actions, and although Summerscale judged the suggestion to be 'ridiculous' in an interview with the Financial Times Magazine, she continued, 'I’m not totally dismissive of the idea. You can’t have it both ways – you can’t think that books and TV and film shape people, and then say that they’re completely irrelevant when people do bad things.' It is a typically considered and clear-sighted remark from a writer for whom the porous boundary between fact and fiction has proved so fertile.

Stephanie Cross, 2016