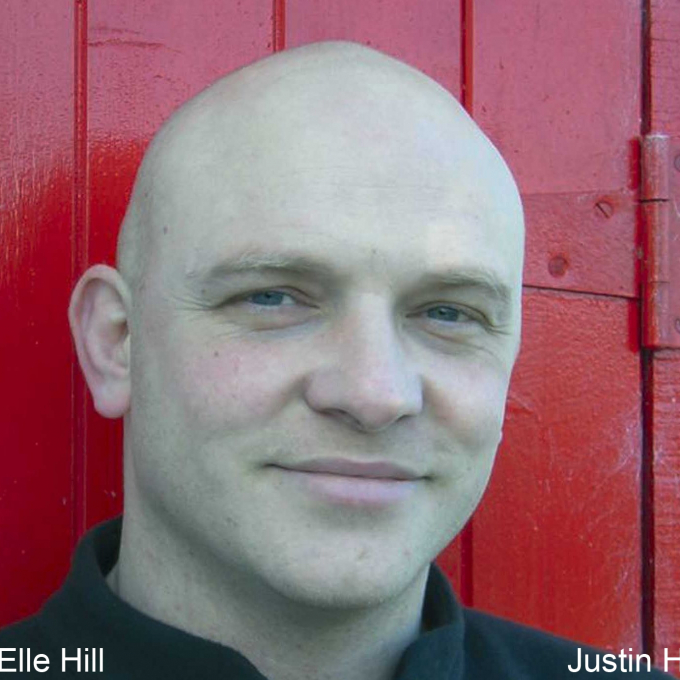

Justin Hill

- Bahamas

Biography

Justin Hill was born in the Bahamas in 1971, and moved to the family's native Yorkshire three years later.

He studied English Language and Medieval Literature at Durham University, and went to work in rural China at the age of 21, as a volunteer for the aid agency, Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO). He spent eight years as a volunteer in China and Eritrea, East Africa, and was airlifted out of Eritrea in 1998 when war broke out with Ethiopia.

His first book, A Bend in the Yellow River (1997), written when he was 22, is a portrait of small town China. His second book, Ciao Asmara (2002), is an account of the Eritrean struggle and was shortlisted for the 2003 Thomas Cook Travel Book Award.

After returning to England, Justin Hill wrote his first novel, The Drink and Dream Teahouse (2001), set in contemporary China, which won the 2003 Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, and a Betty Trask Award, was translated into ten languages and was banned in China.

In 2001 Justin Hill was listed in the Independent on Sunday as one of the 'Top Twenty Young British Writers'. His second novel, Passing Under Heaven (2004), tells the life of China's foremost female poet, Yu Xuanji, who lived in the final years of the Tang Dynasty (AD618-907).

Shield Wall, a chronicle of events leading up to the Battle of Hastings - the first in the 'Conquest' series - was published in 2011.

Justin Hill taught at City University of Hong Kong between 2009 and 2015, where he ran the undergraduate Creative Writing course.

Critical perspective

Justin Hill is a novelist and travel writer with a growing international reputation, whose writing has been mostly associated with the people, culture and history of China.

His first book, A Bend in the Yellow River (1997), draws upon his experiences and observations during two years teaching English at a college in Yuncheng, a rural town in the northern province of Shanxi. He has gone on to publish two award-winning novels. The first of these, The Drink and Dream Teahouse (2001), was officially banned in China, probably for its explicitness in portraying contemporary sexual and financial mores, the human costs of the government’s transition to a so-called socialist market economy. Passing Under Heaven (2004), set in the late Tang Dynasty, also evokes an era of political turmoil; within this, it brilliantly re-creates the passionate and ultimately tragic life of China’s first woman poet. By contrast, Ciao Asmara (2002) is an account of Hill’s second stint of teaching abroad, at a high school at Keren in Eritrea, which was cut short by being airlifted out of the country during the 1998 war with Ethiopia.

Hill taught at the City University in Hong Kong as well as being writer in residence at Lingnan University from 2009 to 2015. He appears frequently at literary festivals, both in Hong Kong and mainland China, and has recently contributed short stories to both Asian Literary Review (Summer 2010) and the anthology 50/50: New Hong Kong Writing (2010). Back in February 1993, however, his first impressions of Yuncheng had been unpromising. He quickly realized how different it was ‘from the China of my imagination’ and how ‘dust in Yuncheng is like water in Venice’. A Bend in the Yellow River records bewilderment at being the object of curiosity in the street, a lack of personal space and, perhaps most of all, the customary ‘polite’ use of physical force. With the improvement of Hill’s spoken Chinese, his naivety lessens, and being a LaoWai [foreigner] gives him a good vantage point to observe Chinese society in transition, as it attempts to reconcile its Buddhist heritage and Communist traditions with new economic imperatives.

Vividly described banquets, marriage customs - and sometimes challenging encounters with the local cuisine and strong liquor - ensue. Personal and economic relations, he notes, seem to go together amongst his students and teaching colleagues, notably in the importance of guanxi (good relations, influence) for obtaining jobs and housing. This factor is pervasive throughout The Drink and Dream Teahouse, where it functions as much in obligations to family members as in bribery. The novel’s title ironically refers to a brothel, one among many profitable enterprises, including nightclubs and karaoke bars, now owned and run by representatives of The People’s Liberation Army.

These inevitable tensions between old Communist values and the new Capitalist economics bring conflicts between its multi-generational cast of characters. Many want to ‘get rich’, while others bitterly resent this. As the novel opens, in Shaoyang the imminent closure of the Number Two Space Rocket Factory brings despair to veteran local Party Secretary Li. He responds by making banners denouncing official corruption and then hanging himself. His mourning wife senses a return to the chaos of ‘the past, locked into the present and turning over and over’. Their neighbours are more stoical, though also worried. We soon meet them: opera-singing Madame Fan and her lovely daughter Peach; and Old Zhu, survivor of the Cultural Revolution, who summons his son Da Shan back from a lucrative job in Guangzhou. Da Shan’s former lover Liu Bei – with whom he was involved in the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests – is now working as prostitute Pale Orchid at the Drink and Dream Teahouse. Da Shan soon finds himself the object of neighbourhood match-making interest, though he desperately wants to find Liu Bei again, and their child. Meanwhile, ambitious army officer Fat Pan needs Da Shan’s Guangzhou contacts to provide capital for further property deals. Hill’s relative explicitness about sexual encounters and financial dealings are dramatically justified. But he interpolates these with some delicate descriptions of nature: ‘before dawn, in the silver moonlight, a cherry bud opened in a slow and silent explosion of petals’.

Passing Under Heaven, by Hill’s own account, arose out of translations of poems by Yu Xuanji, China’s first and foremost woman poet. It evocatively summons up an era of both delicate cultural refinement and official cruelties. It has an elegiac feel, as the Tang Dynasty crumbles: ‘the exquisite gardens, painters, poets, musicians and courtesans had all survived a precarious existence until war swept them away, leaving nothing to brighten a land devastated by suffering, except memory’. Yu Xuanji herself also comes vibrantly to life. She grows up from an orphaned childhood as Little Flower, learning how to write and maturing sexually, becoming the alluring if rebellious concubine of a high state official. The action switches between two narratives roughly 50 years apart. In one, elderly and impotent Minister Li is dying, while the empire is overrun by barbarian invaders. In the other, the on-off passionate love between Li and his concubine stimulates her developing literary gift, her jealousy, and their blazing arguments.

Despite their strong and frequently renewed mutual sexual attraction, her determination not ‘to submit to the rules of propriety’ makes them ‘like two armies bent on each other’s destruction’. By now drinking and behaving erratically, Yu Xuanji is punished by a clique of traditionalists led by The Upright Magistrate. They are unhappy with her increasing fame as a poet but also her unwise friendship with Wen Tingyun, a veteran poet whose criticism of the Emperor leads to him being beaten to death. Yu Xuanji eventually accepts her fate philosophically: ‘Any man’s life is mapped out by the poems he writes … as stars make up constellations’. In a quietly moving scene of reconciliation, Li at last brings their baby to see her in prison.

Passing Under Heaven contains some violent episodes. No doubt there will be battle scenes in Hill’s forthcoming novel, Shield Wall (2011), due to be the first in a projected trilogy, opening in the England of 1016. Its warrior hero is Godwin, who joins the son of Saxon King Ethelred in fighting against the Viking invaders, as events are set in motion towards the Norman Conquest of 1066. This may seem like a startling new turn for Justin Hill’s fiction, but he has already shown his mastery of the historical novel. He is able to re-create ancient eras beautifully, and fully engage our sympathies for the lives and loves of his characters.

Dr Jules Smith, 2010

Bibliography

Awards

Author statement

On Writing

I

This evening my two-year old son came out of his bedroom. I had put him to bed half-an-hour earlier, but he has just learned how to open a door, and this is a marvellous thing for him: to take doors that have always been closed and open them wide.

He could tell I was not happy. I didn’t need to speak.

‘Horse!’ he said and ran out three steps and picked up a plastic horse that has lain lost under his bed for the last two weeks.

He closed the door behind him, and did not come out again.

It was later that I went into his room, saw him in the dim arc of light from the doorway, face down into the pillow, the horse still clutched in his hand and this moment – the door, the horse, his fist clenched round it – and me, his father watching.

And I thought that this, in a crowd of other reasons – pleasure, success, the need to tell an untold story - is the real reason why I write: to capture the fragile beauty of our days, which are daily lost and forgotten.

II

Bruce Chatwin said of his first book that it was a cubist travelogue: continually shifting viewpoints and styles to give a complete view of Patagonia. I read that sentence before I appreciated what it meant, but as I began to look long and hard at what I wanted my writing to do and feel like, I went back to that sentence and tried to visualise what it meant as a writer to approach a subject as a cubist; or a surrealist; or a landscape painter. A day kept coming back to me, from my first summer in Xian, the ancient capital of China, when I stood in a shaded room and watched a Chinese master painter at work.

He was a short plump man with ink-black dyed hair. He smiled as he welcomed me, took a white sheet of paper, drew in a single bold movement three green lines up the page. These were the stem of the bamboo. The next sweep of his arm added the shaded side of the bamboo. The next added the notches that connected each section of bamboo, and the twigs to either side, and the leaves. The bamboo grew with breathtaking speed. In less than a minute it was done. The brush had touched the page no more than 20 times. It was so sudden I laughed, with the same surprise and mistrust as if he had performed a magic trick before my eyes. But to achieve that level of skill had taken him decades of perfecting.

Traditional Chinese painting differs not only in the techniques, but also in the artists’ aspiration. Chinese master painters specialise: bamboo; fish; chrysanthemums; tigers. Painting is a kind of meditation, performed without conscious thought, like meditation, in a moment, letting the feeling guide the arm and the brush. They leave almost all the page blank, a fact that astonished me at first, because looking at the picture the painting seemed to fill the paper. And Chinese artists do not paint a specific fish or tiger, but – in the same way that Borges writes of his tiger – they want to paint a tiger that holds the essence of all tigers. They do, in short, attempt to paint the universal in the specific.

These ideas resonated for me as a writer trying to define for myself what I was trying to achieve. How to translate these ideas into writing? It works, for me, in the attempt to make each detail as clear and efficient as possible, to distil the language as finely as possible and – and this is the finest balance to make – to leave as much white paper on the canvas as possible, whilst leaving the reader with the impression that they are looking at a picture as detailed as any photograph. To achieve the illusion that the reader is sharing the lives of characters as real and feeling and strange as any other person we might pass in the street.