- ©

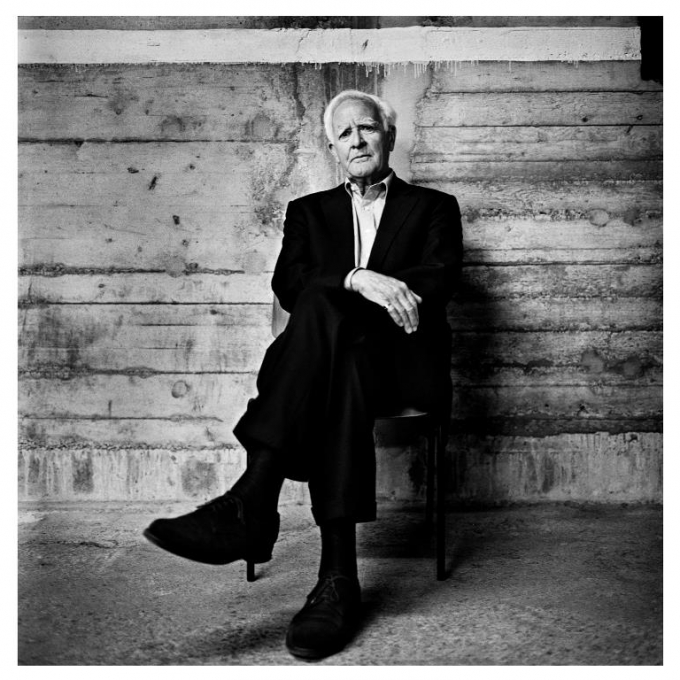

- Anton Corbijn

John le Carré

- Dorset

Biography

John le Carré (aka David Cornwell) was born in Dorset in 1931, and was educated at Sherborne School and the University of Berne, before reading modern languages at Oxford University. He taught at Eton from 1956-58, then spent five years in the British Foreign Service until 1964.

He started writing in 1961, and his first novel, a spy thriller, was Call for the Dead (1961), later made into the film The Deadly Affair starring James Mason. This was followed by A Murder of Quality (1962), a detective novel set in a boy's school, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963), the novel which brought him worldwide public attention, which tells the story of the last assignment of an agent who wants to end his espionage career.

Since then, John le Carré has written many novels, including a series which feature the character George Smiley: Call for the Dead (1961), Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), Smiley's People (1980) and The Secret Pilgrim (1991). Other novels, all of which have been made into successful films, are: The Looking Glass War (1965); The Little Drummer Girl (1983); The Russia House (1989); The Tailor of Panama (1996); and The Constant Gardener (2001). In 2005 the film of The Constant Gardner, starring Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz, opened the London Film Festival. The book won the 2006 British Book Awards TV and Film Book of the Year.

John le Carré's latest novel is A Delicate Truth (2013). He worked with screenwriter Peter Morgan on a film adaptation of Tinker,Tailor, Soldier, Spy, which was released in September 2011, starring Gary Oldman as George Smiley. Eight of his 'Smiley' novels have been dramatised for BBC Radio 4 and were broadcast during 2009 and 2010. He was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2011.

Critical perspective

David Cornwell, better known by his nom-de-plume John Le Carré, is, quite simply, a natural storyteller, a master.

In the enviable position of being a critically acclaimed writer who tops international bestseller lists he is, like Graham Greene, without whom there may never have been a Le Carré, able to combine complex, thrilling plots with a measured, formal narrative style.

Le Carré has always had an alchemical ability to make fictional gold out of his real life experience working in intelligence, creating some of the best spy fiction ever written. In his work, MI6 becomes the 'Circus'. That name alone informs us that Le Carré’s world is not that of Ian Fleming. 'What do you think spies are: priests, saints and martyrs?' Leamas asks Liz in The Spy Who Came In From The Cold (1963), the novel which established Le Carré’s reputation: 'they’re a squalid procession of vain fools, traitors, sadists and drunkards, people who play cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten lives. Do you think they sit like monks in London, balancing the rights and wrongs?' The Spy Who Came In From The Cold has had extraordinary cultural resonance. Greene described it as 'the best spy story I have ever read'. Even those who haven’t read it are aware of its presence; it has become part of the culture. The tale of Leamas, forced to play the role of a lost, aimless, drifting ex-agent so as to be able to destroy the East German Mundt, someone whom the Circus have long wished to apprehend, is, from its stunning opening, full of a lingering sadness, both moral and intellectual. Terse, suspenseful, and powerfully gripping, it has an atmosphere of chilly, end of days darkness, and is arguably the best of Le Carré. Many consider what is often known as The Karla Trilogy, to be Le Carré’s finest achievement, but, whilst its range and impact is undeniable, I do not think that any of the three novels has the black punch which makes The Spy Who Came In From The Cold a near flawless piece of work.

The Karla Trilogy gives centre stage to the iconic George Smiley, who appears in a minor role in the early novels. Out of retirement and acting head of the Circus, we follow his battle with Karla, his Russian nemesis, across continents and within his own establishment. The novels are engrossing and full of brilliant flashes - the relationship between Smiley and his team in all three and particularly in Smiley’s People (1980), the descriptions of an Asian continent ravaged by war in The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), the manner in which Smiley goes after the Russian mole in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974) - but the novels work best when George Smiley is present. When he is not there, they somehow fade. Described in Tinker, Tailor, Solider, Spy as 'small, podgy and at best middle-aged … one of London’s meek who do not inherit the earth', it is Smiley’s insularity, his meticulousness, his lack of physical grace and his undoubted brilliance as both a field man and head of the Circus, that draws us in; it is never less than fascinating to watch him operate. Smiley is a master spy, but a man with a personal life in free fall. Unlike Bond, who is of course a fantasy object, George Smiley is real and flawed; he elicits sympathy and awe. With no hint of exaggeration he is amongst the most memorable fictional characters of the 20th century.

In a career spanning more than 40 years, Le Carré has written 19 novels. The majority concern themselves mostly with espionage but there has also been a love story, The Naïve and Sentimental Lover (1971), which was poorly received, a semi-autobiographical study of his troubled relationship with his father; A Perfect Spy (1986), considered by many to be his masterpiece; and an attack on Western greed in Africa, The Constant Gardener (2001), recently made into an Oscar winning film.

One book stands out in Le Carré’s oeuvre, in the way in which it demonstrates the author’s natural flair for comic narrative, a facility Le Carré has perhaps never fully exploited. Whilst his sardonic humour is never absent from any of his novels, it is in The Tailor of Panama (1996), inspired by Greene’s Our Man in Havana, that he gives it a freer reign. Andrew Osnard, a young, headstrong agent, whose mission it is to keep an eye on the political manoeuvrings leading up to the handover of the Panama Canal on 31 December 1999, hires Harry Pendel, proprietor of Braithwaite Limitada. Osnard wants Pendel to supply him with vital information on the Panamanian underground and keep him abreast of the talk around town. Pendel, tailor to the great and the good, is a deliciously drawn protagonist, whose lies and betrayals eventually begin to get the better of him. Satirical and at times farcical, The Tailor of Panama is, like the novel it is a hymn to, full of a sense of impending political chaos; it amuses and entertains yet it also provokes and unsettles.

This last point is key to Le Carré. He is the most politically aware of authors. His fiction engages fully and passionately with the times. He enters charged arenas like the Arab/Israeli conflict in The Little Drummer Girl (1983), and offers not only a thrilling entertainment, but also a considered study of the situation. He gives warning while providing pleasure; his storytelling is fuelled with a need to take the world to task, to unearth failures of justice and abuses of power and privilege, to offer insights into the minds of those who find themselves in extraordinary circumstances.

This is particularly evident in Le Carré’s most recent novel, Absolute Friends (2004), as angry, passionate and complex a book as he has ever written. Absolute Friends is a deliberately provocative analysis of the current 'War on Terror', something which could have unseated a lesser writer. It is cogent, witty, tender, touching and, at its end, devastating both in what transpires and in the sudden brutal economy of the narrative. The story of Ted Mundy and Sasha, who first become friends in the Berlin of the late 60s, meet again as agents in the Cold War, then come together once more in the present day world of terror and lies, it is fuelled by a deeply engaged, moral sensibility. Whatever our politics we must answer the questions Le Carré poses. Allied to the bitter rage, there is a sober, rational, precise intelligence that cannot be ignored. This novel belongs at high table, with the very best of Le Carré’s work; it proves, if nothing else, that there’s not only life in the old dog yet, but new direction. John Le Carré has, like, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler and Graham Greene, transcended a genre, and made literature. His work is notable for its meticulous construction and its immensely detailed, rich, elegant style. Le Carré has a gift for deep and subtle characterization. This from the opening of Absolute Friends: 'a failure at something – a professional English bloody fool in a bowler and a Union Jack, all things to all men and nothing to himself, 50 in the shade, nice enough chap, wouldn’t necessarily trust him with my daughter. And those vertical wrinkles above the eyebrows like fine slashes of a scalpel, could be anger, could be nightmare, Ted Mundy, tour guide'. In one paragraph - strangely reminiscent in its beat and rhythm to the opening of Nabakov’s Lolita - we have a full flavour of the character. Le Carré is to be cherished. He is, as The Observer says, 'a literary master for a generation'.

Garan Holcombe, 2006