- ©

- Carolyn Djanodly

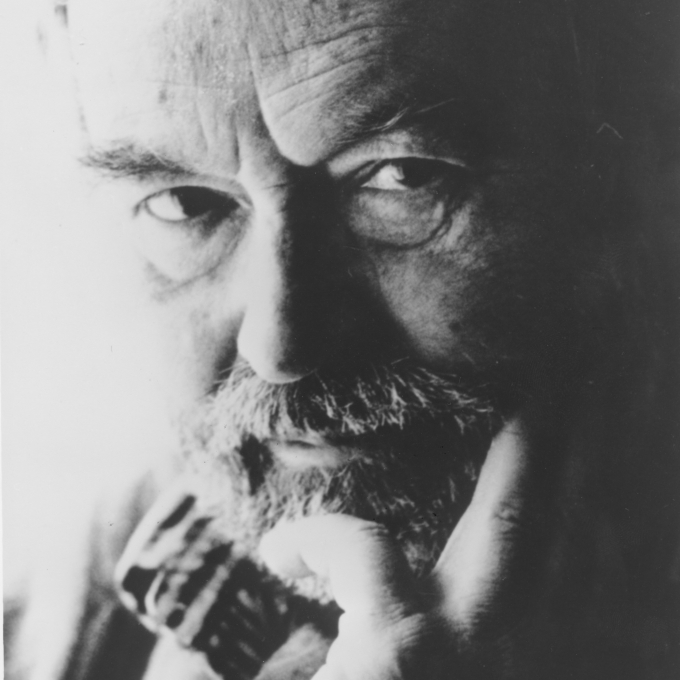

John Fowles

- Leighton-on-Sea, England

- Sheil Land Associates Ltd

Biography

John Fowles was born at Leighton-on-Sea, Essex in 1926, where he lived until the outbreak of the Second World War.

He was educated at Bedford School and New College, Oxford, where he read French and German. After graduating he taught English at the University of Poitiers and then at the Anagyriou School at Spetses. He became a full-time writer in 1963.

His best-known fiction includes his first novel, The Collector (1963), the story of a young clerk, a butterfly collector, who kidnaps a young woman; The Magus (1966), set on a Greek island where a schoolteacher confronts a series of disturbing events; and The French Lieutenant's Woman (1969), a formally experimental novel that tells the tale of Victorian palaeontologist Charles Smithson and his involvement with the notorious and enigmatic Sarah Woodruff. The French Lieutenant's Woman won the Silver Pen Award and the WH Smith Literary Award and was adapted as a film in 1981 with a screenplay by Harold Pinter. Fowles' other fiction includes Daniel Martin (1977), Mantissa (1982) and A Maggot (1985).

John Fowles lived in Lyme Regis in Dorset on the south coast of England and was for a period curator of the local museum. He was an avid collector of old books and china and a fascinated student of fossils. The Tree, published in 1992, is partly a memoir of childhood and explores Fowles' enduring love of nature. He also published a Short History of Lyme Regis in 1982 and was the editor of Thomas Hardy's England (1984). His last book, The Journals: Volume 1 (2003), is the first volume of the journal he began as a student at Oxford in the late 1940s and continued over the next half century.

John Fowles died in November 2005.

Critical perspective

John Fowles enjoys a justifiably high standing as both a novelist of outstanding imaginative power (in some ways a modern-day Thomas Hardy, especially as a chronicler of his beloved Dorset), and as a highly self-conscious 'postmodernist' author who fully registers the artifice inherent in the act of writing, the fictiveness of fiction itself.

His novels began with an original psychological thriller, The Collector (1963), but his reputation was made by his two best-known novels The Magus (1966), and especially The French Lieutenant's Woman (1969) with its vivid pastiche of Victorian fiction and famous device of 'alternative endings'. Fowles' writing is dominated by the consciousness of the author as a figure within his own books, entering the narrative at certain points to comment on the action, the characters' motives and possibilities, and explain how things might have been different. Able with equal ease to transform futures or point out absurdities, the novelist is a capricious, no longer an omnipotent god; a magician whose tricks may all be bogus; or simply a late-arriving, rather seedy impresario, as in the denouement to The French Lieutenant's Woman. Exercising free will, playing with fiction's constraints and conventions, the writer's authority is nevertheless relative: appropriate for an era of relative not absolute values. All of Fowles' large, capacious novels are incredibly rich reading experiences, from the labyrinthine plot twists of The Magus and the international panoramas in Daniel Martin (1977) to the brilliant recreation of the eighteenth century mind set in A Maggot (1985). They operate on the reader's consciousness on several levels at once; as page-turning narratives with memorable characters, demonstrations of the novelist's craft, historical and political commentaries; and as profound reflections on the whole spectrum of human behaviours.

By his own account, Fowles was much influenced, during and after his student days at Oxford in the late 1940s, by the cultures of ancient Greece (especially the philosopher Heraclitus) and modern France, from Flaubert to post-war Existentialism and the nouveau roman. In The Aristos (1965), Fowles set out his ideas on 'the essential mystery in art', religion and its rituals, ethics, politics (no truck with 'quasi-emotional liberalism') that inform much of the drama, as well as the author's commentary, within his subsequent novels. Fowles' own fascination with the 'Circe-like quality' of Greece found unforgettable expression in his first great novel, The Magus. Nick, a young Englishman escaping from an unsatisfactory love affair and teaching at the Lord Byron School on the island of Phraxos, falls under the spell of Conchis, a rich mystery man, and the two alluring young English women attached to him. Nick is subjected to a disorientating succession of strange events, conflicting stories from 'actors', and erotic apparitions, during which he experiences echoes of the Greek mythic culture. The book suggests a world beyond ordinary reality but also the bogus mystification of a trickster: a multi-layered, ambiguous commentary on the nature of art and the artist's situation.

The French Lieutenant's Woman is a tale of seduction in two senses: of 'fallen woman' Sarah Woodruff by the highly respectable gentleman geologist Charles Smithson; and of the reader by the author. Fowles offers pleasure and sentiment in the mode of the nineteenth century realist novel, complete with wonderfully realised characters, epigraphs to its chapters, and even sets it in his own town of Lyme Regis in Dorset. But this is written by a modern consciousness, aware of Darwin, Marx and Freud, (not to mention Barthes and Robbe-Grillet) and the wretched mid-nineteenth century conditions of the servant and labouring classes. Set alongside Fowles' socio-historical commentary, the players are made ever more ambiguous author's playthings. Sarah turns out to be an arch manipulator herself, whose story is an almost complete fabrication. Sarah's priggish employer Mrs Poulteney is imagined falling into hell, only to be reprieved by the author. And yet - the scene in which Smithson's naïve fiancée Ernestina is rejected by him is truly affecting. Dickens himself could hardly have bettered the scheming servants Sam and Mary, 'low' characters speaking in local dialect, whose domestic happiness runs throughout as a counterpoint to Charles and Sarah's doomed yearnings. Fowles' cutting through fiction's illusion is, however, shown most starkly when Sarah has fled to a small room in Exeter. She unwraps a toby jug that is sadly cracked, 'as I can testify', the author comments, 'having bought it myself a year or two ago for a good deal more than the three pennies Sarah was charged'.

By contrast with his major novels' vivid and wide-ranging scenes, Mantissa (1982) takes place entirely within the mind of the novelist Miles Green, who is in hospital following a stroke. A small scale jeux d'esprit in the Flann O'Brien manner, its characters take violent revenge upon their creator, in a satirical revisiting of some of the preoccupations of Fowles' writing, sending up modish critical jargon and the pretensions of literature itself. The recumbent novelist's fantasies about the female medical staff (the Caribbean nurse Cory, and a shapely specialist in abnormal brain behaviour 'Dr A. Delfie') becomes a splenetic exchange about art and ethics with the Muses. Their traditional function as erotic inspiration for the male writer's craft has become comically outmoded by their status as modern women; withering exchanges between them and the hapless Green provide the entertainment.

Fowles' dialogue, particularly the perennial verbal warfare between the sexes, is always incisive. Never more so than in Daniel Martin and A Maggot, books overshadowed by their grand predecessors but having attractive qualities of their own. Daniel Martin has elements that are tempting to read as semi-autobiographical: a rural West Country childhood during the Second World War, Oxford student friendships and love affairs, career involvement with the film industry. What it also has is some marvellous travel writing on Egypt and Syria, as its scriptwriter scouts locations for a movie and takes up again with his former lover; and a good deal of now very dated political debates from the 1970s. A Maggot is more satisfying though less ambitious. Set during 1736, it is not, as the author comments, a conventional historical novel about the mother of Ann Lee, founder of the Shaker sect. Rather, its eighteenth century world of religious visions and gross human appetites is presented in sections, as a lawyer interrogates a range of conflicting accounts, from actors to a brothel madam, about the apparent suicide of a deaf mute servant. Its main female character is, like Sarah Woodruff, a 'fallen woman' who undergoes a transformation: submissive prostitute Fanny becomes the fearless Quaker Rebecca. This shifting of identity before our very eyes during the teasing progression of a plot, with the direction of author himself, is what we identify as 'Fowlesian'.

Dr. Jules Smith, 2002

For an in-depth critical review, see John Fowles by William Stephenson (Northcote House, 2003: Writers and their Work Series)

Bibliography

Author statement

'I don't very often have the courage of my convictions face to face with people. This is why I became a novelist. If I was asked to pick the school child most likely to become a writer, I'd pick the shy boy or girl, the one who never manages to stand up for his or her beliefs. Who walks away from a lost argument thinking of all the answers that would have won it ... When I am inside a text I can say what I like. Not only about politics. I can be franker about sex, for example ... '