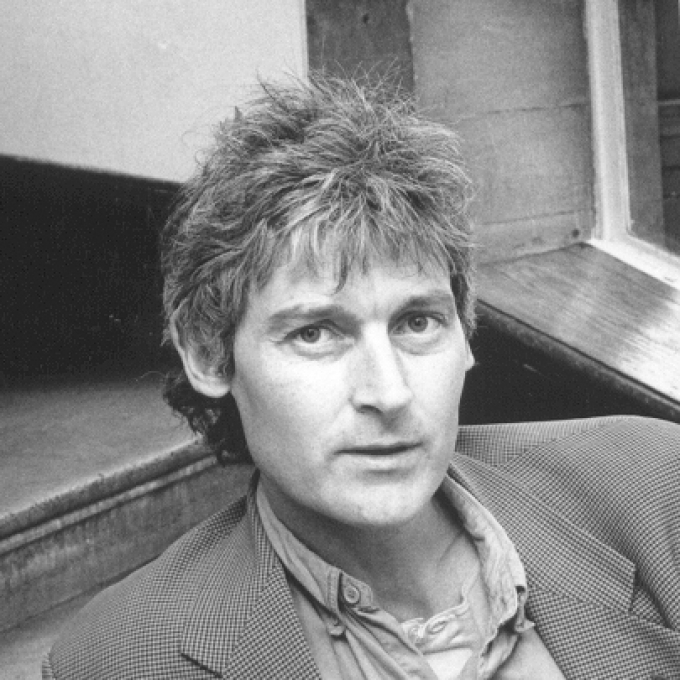

- ©

- Norman McBeath

Biography

Jamie McKendrick was born in Liverpool in 1955, studied at Nottingham University and taught for some time at the University of Salerno in Italy.

He is the author of six collections of poetry: The Sirocco Room (1991); The Kiosk on the Brink (1993); The Marble Fly (1997), winner of the Forward Poetry Prize (Best Poetry Collection of the Year) and a Poetry Book Society Choice; Ink Stone (2003), shortlisted for the 2003 T. S. Eliot Prize and the 2003 Whitbread Poetry Award; Crocodiles and Obelisks (2007), shortlisted for the 2008 Forward Poetry Prize (Best Poetry Collection of the Year; and Out There (2012). His selected poems have been published in Holland and Italy.

In the 1990s, Jamie McKendrick was named as one of the Poetry Society’s ‘New Generation’ poets. He lives in Oxford, where he teaches part-time and reviews poetry and the visual arts for a number of newspapers and magazines. He has held residencies at Hertford College, Oxford, Masaryk University, Brno, the University of Gothenburg, and at University College, London. He is editor of the recent Faber Book of 20th-century Italian Poems (2004), and is currently working on a translation of the poetry of Antonella Anedda.

His translation of Valerio Magrelli's book, The Embrace: Selected Poems (2009) won the 2010 John Florio Prize for Italian Translation and the 2010 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize.

Critical perspective

In the poetry of Jamie McKendrick, natural processes can be both sobering and amusing.

In ‘Ill Wind’, from his first collection, ‘A week before, the sirocco had come / with its tiny pouches of sand, transplanting / one grain at a time the whole Sahara’. Although the world as McKendrick reads it is not especially accommodating, it clearly deserves his careful, even minute attention, for example to the mysterious way in which, in a neighbouring poem, ‘Frail Weave’, the sea ‘signals itself / by an inkling long before / the hightide crashes on the ear’.

Richly and variously visual, McKendrick’s imagination is drawn both towards and away from interpretation. The world of detail ought to be enough, but the mind cannot rest there for long. The surface of a water-butt shows the speaker’s eyes ‘floating / / half closed, Chinese / on the green dome / of the water

dark / like two canoes / conveying jewels / to their own kingdom.’ Even here, in a moment of purely aesthetic pleasure, the wry insurance of humour is never far away.

A large set-piece such as ‘Signs’, which reads like a diary of ‘civilian’ city life during the 1984-5 miners’ strike, would seem to depend on interpretative coherence if despair is to be avoided, but rather than merely protest at circumstances – the government has ‘squads to spare to send out against pickets’ - McKendrick takes the temperature of England through the details of more local discomforts in a suburban street, recording the itchiness and intolerance of virtually everyone, in the face of uncontrollable change. The speaker, finding that teenagers have destroyed a rowan sapling, recalls that the Celts ‘would flay alive / the culprit and use his skin to bandage the pith. / Virulent Manx justice!’

‘It made no sense to me,’ says the speaker in ‘Decadence’, ‘ but sense was not what I was after. I wanted dreams.’ Dreams, visions and states of (usually uneasy) reverie are an important means of entry for McKendrick to the classical world of Italy, whose pull on him is as powerful as anything the present day has to offer. ‘Nostalgia’, from the impressive sequence ‘Lost Cities’, recalls, or re-dreams, a Sicilian palace and the unease of waking ‘drenched in sweat and homesick / for nowhere I could think of, a feeling / scuffed and quaint as farthings or furlongs.’ The movement of the poem, almost imperceptibly towards a sense of vertiginous threat, recalls the cultural-historical odysseys, at once engaging and disquieting, undertaken in the work of W.G. Sebald, where seemingly ordinary activity opens on to something close to nightmare. McKendrick seems to share Sebald’s sense that the observer, the latecomer, is as inextricably bound up in history as its original actors. This helps to avoid the kind of melodramatic opportunism to which, for example, contemporary fiction is sometimes drawn. History may in a sense be theatre, but the audience cannot actually leave and go home.

McKendrick’s power of disquiet is as much textural as thematic. ‘Under the Volcano’, from McKendrick’s second collection, The Kiosk on the Brink (1993), watches arson on the slopes of Vesuvius – a rite of passage for the young, he suggests – and notes: ‘You sense the sulphur under the earth’s crust’, though ‘no one’s / the wiser as when the camorra / firebomb a disco or bar’. Rather than simply assert that there exists in Neapolitan life a loyalty to forces which liberals might not care to recognize, McKendrick sets up a labyrinth of half-rhymes and echoes, a kind of auditory rumour, ramifying like the city itself. Adjacent versions from Montale and Machado further develop the underworld theme, while ‘Skin Deep’, which observes an octopus changing its appearance – ‘It thinks in colour’ – also considers, with resigned bitterness, how the ingenuity of Creation can be rendered down ‘to an inky sauce, some Redon lithograph / of spiders dancing in the afterlife.’ A truism – change and decay – is thus re-animated.

McKendrick opened his award-winning collection, The Marble Fly (1997), with a characteristically crisp summing-up, in the chronicle-poem ‘Ancient History’:

‘The year began with baleful auguries:comets, eclipses, tremors, forest fires, the waves lethargic under a coat of pitch

the length of the coastline. And a cow spoke,

which happened last year too, although last year

no one believed cows spoke. Worse was to come.

There was a rain of bloody lumps of meat …'

Even disaster and hopelessness can have the merits of familiarity, it seems, even the complete transformation of earth and water in ‘Paestum’, where the diver whose picture decorates his tomb, is suspended between earth, ocean and the fires of the underworld.

McKendrick is now prepared to pursue a poem off the familiar charts, to turn away from ‘satisfying’ closure, to raise his voice a little while developing his interest in sonnets, such as ‘The Spleen Factory’, after Carlos Drummond de Andrade:

'I want to make a sonnet that’s not a sonnet

according to any civilized notion of what

that is. I want it ugly as concrete,

and just about impossible to read.

And I’d like my sonnet in the future

to give no living soul an ounce of pleasure,

not by being merely foul

mouthed and perverse

but also (why not?) by being both and worse.'

The pleasures of the text are, of course, subtle enough to incorporate this powerfully anaesthetised dissent from art. We might read the poem as a retreat undertaken in order to launch a fresh attack. The poem will be

'… a wall with a hole pissed through – in the hole a star

transmitting incomprehensible clarity.'

That glimpse of ‘incomprehensible clarity’ not only suggests an aspiration to make in art what has been witnessed in life, but also serves as a talisman against the temptations of exotic anecdotalism to which more than one English poet (Lawrence Durrell being perhaps the most notable) has succumbed. McKendrick faces up to the possibility of subjects even drier and grimmer than his wit: see the agave in ‘The Century Plant’, for example, or the ingenuity with which ‘A Shattered Bridge’ (from the 2003 collection Ink Stone) considers the nature of bridges, of flying and falling and being thrown.

With Ink Stone, the best of an impressive series of books, McKendrick seems to have gained a significant authority. This has something to do with an increasing naturalness of utterance, instanced by the memorable ‘Salt’, after Montale, and by a corresponding lack of anxiety in the marshalling of his material. ‘Basilisk’, for instance, takes on the subject of Venice as if there simply were no bristling fleets of literary antecedents to clutter the poem’s course. The poem overlays a mural with the sight of a vaporetto’s conductress mooring her vessel:

'She might have stepped straight out of that

Mural I’ve just been to see

Where a small female saint subdues

The scaly basilisk and leads it

Still trembling with lust on a length of cord-

it must be silk – across the square and through

the parting crowd – it must be here

where the sea’s edge drapes its hard green lace

on polished stones our feet perceive as waves.'

Such imaginative richness and sensuality, along with his urgent wit, place McKendrick among the most interesting, surprising and distinctive poets of his generation.

Sean O'Brien, 2006