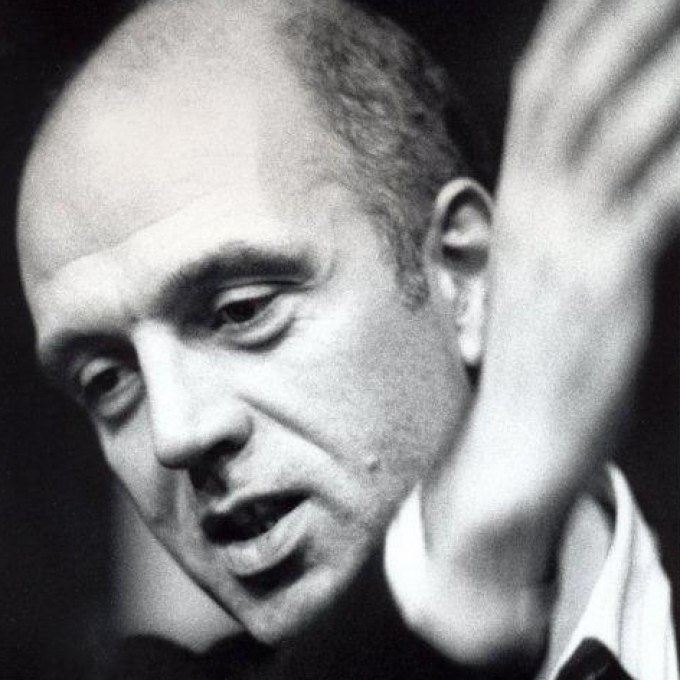

Biography

Poet and critic James Fenton was born in Lincoln in 1949, and was brought up in Yorkshire and Staffordshire.

He was educated at a musical preparatory school attached to Durham Cathedral, where he was a chorister, progressing from there to Repton public school in Derbyshire. He then studied for three years at Magdalen College, Oxford.

In 1968 he won the Newdigate Prize for best poem by an Oxford undergraduate on a set subject, later published in pamphlet form as Our Western Furniture (1968). After graduation he became a freelance journalist before joining the staff of New Statesman.

His first full poetry collection was Terminal Moraine (1972), after which he won an Eric Gregory Award, using the money to travel to South East Asia as a freelance reporter. He returned to become New Statesman's political correspondent at Westminster, and over the next few years worked for various newspapers as journalist, critic and reviewer.

His poetry collection, The Memory of War: Poems 1968-1982 (1982), based on his experiences in South East Asia, brought him to public attention, and was followed by Children in Exile in 1983. His second poetry collection is Out of Danger (1993).

James Fenton has also written several books of non-fiction, including Leonardo's Nephew: Essays on Art and Artists (1998), A Garden from a Hundred Packets of Seeds (2001) and The Strength of Poetry (2001).

He became Professor of Poetry at Oxford University in 1994, and in 2002 wrote An Introduction to English Poetry (2002). He has also translated two operas: Rigoletto (1982) and Simon Boccanegra (1985) for the English National Opera. His libretto from Salman Rushdie's Haroun and the Sea of Stories was performed by New York City Opera in 2003, and in 2004, his translation of Tirso de Molina's Tamar's Revenge was performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company.

His book, School of Genius (2006), is an illustrated history of the Royal Academy from its foundation to the present day. A Selected Poems was also published in 2006.

James Fenton has edited The New Faber Book of Love Poems (2006) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (2006).

In 2007, James Fenton was awarded the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. His most recent poetry collection is Yellow Tulips (2012), a gathering from four decades of work, features his most recent, uncollected work.

Critical perspective

The name which arises most frequently in discussions of James Fenton is that of W.H. Auden. Like Auden, Fenton was a youthful prodigy. He published his first full collection, Terminal Moraine (1972) in his twenty-third year and rapidly established a reputation as one of the most important and influential poets of his generation.

Although Auden’s influence could be traced in Fenton’s poems and the two men had common political concerns Fenton was none the less an original poet capable of shaping the taste and understanding of his period, rather than merely reacting to it.

Terminal Moraine is both slim and remarkably diverse. It ranges from the masterly set-piece of ‘The Pitt-Rivers Museum’, where the great disorderly storehouse becomes a metaphor of the minds which furnish it, to found poems of various kinds, via the ambitious sonnet sequence ‘Our Western Furniture’, which deals with America’s efforts at the economic colonization of Japan in the nineteenth century. Fenton also proves himself as much at home with rococo nonsense verse as with the Audenesque ottava rima of the ‘Open Letter to Richard Crossman’ (R. H. S Crossman, Labour cabinet minister and then editor of The New Statesman, for which Fenton went on to write, and where in 1979 he coined the term ‘Martian’ to describe the poetry of Craig Raine).

The Memory of War and Children in Exile: Poems 1968-1983 (1983) adds 15 poems to those retained from Terminal Moraine and contains Fenton’s major work to date – ‘A German Requiem’, ‘Nest of Vampires’, ‘A Vacant Possession’ and ‘A Staffordshire Murderer’, some of the most important poems written in English since the Second World War. ‘A German Requiem’ deals with the poisoned legacy of Nazism in the German psyche:

'It is not what you have written down.

It is what you have forgotten, what you must forget.

What you must go on forgetting all your life.'

With great skill Fenton unites this public mode with the omissions and blanks produced by guilt and neurosis, moving the poem at the pace of a funeral cortege to bespeak the moral exhaustion of its inhabitants, at the same time as suggesting the scope and ingenuity of self-justification:

'But come. Grief must have its term? Guilt too, then.

And it seems there is no limit to the resourcefulness of recollection.

So that a man might say and think:

When the world was at its darkest,

When the black wings passed over the rooftops

(And who can divine His purposes?) even then

There was always a fire in this hearth.’

‘Nest of Vampires’ and ‘A Vacant Possession’ are dramatic monologues about the slow death of the propertied classes and their vampiric ability to outlive themselves, though these of course are terms the speakers and other inhabitants of the poems would neither employ nor indeed recognize. These poems remind us of Fenton’s early attachment to Marxism; their rich particularity grounds them in a world of objects, places, discourses and conflicts both generic and tantalizing. They read as satisfyingly condensed novels, original examples of the frequently enigmatic New Narrative poetry (also written by Fred D’Aguiar, Alan Jenkins, Blake Morrison and Andrew Motion), which emerged during the 1980s. The most original of the poems, though, is ‘A Staffordshire Murderer’. The title itself seems to belong in an anthology of folksongs, with ‘A Lincolnshire Poacher’ and ‘The Northumberland Soldier’, as a legitimate category of Englishness, through which society as a whole may be examined:

'The brilliant moss has been chipped from the red barn.

They say that Cromwell played ping-pong with the cathedral.

We train roses over the arches. In the Minster Pool

Crayfish live under carved stones. Every spring

The rats pick off the young mallards and

The good weather brings out the murderers

By the Floral Clock, by the footbridge,

The pottery murderers in jackets of prussian blue.'

‘A Staffordshire Murderer’, with its patented baroque, rooted in Auden but wholly fresh in its instincts, opened a road into a specifically English form of postmodernism, where aspects of Martianism were adapted for historical and political purposes. Fenton, however, elected not to pursue this possibility. To account for this it is necessary to consider the remarkable number of Fenton’s poems which read like outcomes, the perfection of approaches which he has been disinclined to repeat or elaborate. It is as if he has taken to heart Randall Jarrell’s disenchanted observation that Auden succumbed to the temptation to reproduce what he had already mastered. This may perhaps go some way to account for Fenton’s apparently diminishing productiveness as a poet. If there is a unifying principle in his later work, it is expressed in a combination of plainness of utterance with a strong sense of poetry as a public and political art. The results – Manila Envelope (1989) and Out of Danger (1993) - have been widely acclaimed. Although Fenton has set aside the eerie and arresting peremptoriness of some of the earlier poems, ‘Ballad of the Shrieking Man’ is a genuinely nightmarish collision between the external world and the psyche, with hydra-headed nonsense choruses:

'Coffee’s mad

And tea is mad

And so are gums and teeth and lips.

The horror ships that ply the seas

The horror tongues that plough the teeth

The coat

The tie

The trouser clips

The purple sergeant with the bugger-grips

Will string you up with all their art

And laugh their socks off as you blow apart.'

‘Jerusalem’ and ‘The Ballad of the Imam and the Shah’ are plainer but no less unsparing. The love poems are bare, frequently self-accusatory, with a hard-won transparency which suggests that Fenton may have outgrown his interest in some kinds of poetic discourse without replacing them.

In recent years Fenton has worked successfully as a librettist and a playwright. The appeal of public forms and the opportunity to work on a large scale is self-evident. If it is disappointing that Fenton seems to have moved away from the poem on the page, it must be remembered what remarkable standards he set for himself.

Sean O’Brien, 2004