- ©

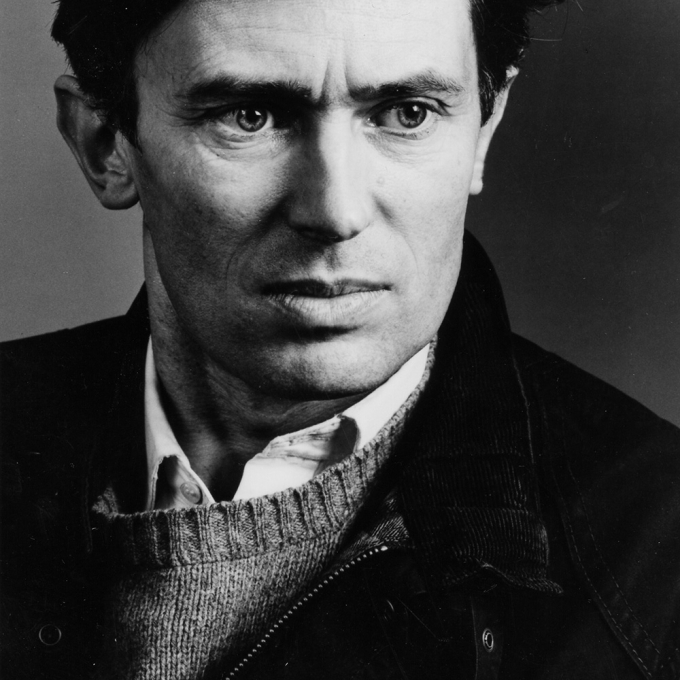

- Caroline Forbes

Biography

Poet, journalist and travel writer Hugo Williams was born in 1942 in Windsor and grew up in Sussex. He was educated at Eton College and worked on the London Magazine from 1961 to 1970. He writes a column in the Times Literary Supplement, has been poetry editor and TV critc on the New Statesman, theatre critic on the Sunday Corrrespondent, film critic for Harper's & Queen and a writer on popular music for Punch magazine.

His Collected Poems, which brings together work from eight books, was published in 2002. His poetry collection Dear Room (2006) was shortlisted for the 2006 Costa Poetry Award, while West End Final (2009) was shortlisted for the 2009 Forward Poetry Prize for Best Collection and the 2010 T. S. Eliot Prize. I Knew the Bride, his eleventh collection of poems, appeared in 2014 and was again shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Forward Prize for Best Collection.

Hugo Williams lives in London.

Critical perspective

Although Hugo Williams has been writing for nearly half a decade now, gathering awards from an Eric Gregory for his first collection, Symptoms of Loss (1965), through to the controversial Billy’s Rain (1999) winning the T.

S. Eliot Prize, he has failed to become a genuinely popular poet and has received little in the way of real critical attention. This is all the more surprising given both his accessible poetic style and provocative subject matter: open, deceptively simplistic poems that blend a civilised, charming narrative style with the often sensational vicissitudes of human relations; ‘showing us’, as Adam Philips once noted in the Observer, ‘what is so strangely undramatic about our personal dramas’. Stranger still when considering the appeal and resonance that pieces like ‘Rhetorical Questions’ hold, as in the poem’s final lines and their pitch-perfect description of sexual pleasure: ‘Do you think I mind / when the blank expression comes / and you set off alone / down the hall of collapsing columns?’

Born in Windsor in 1942 to the actor Hugh Williams and the actress Margaret Vyner, Williams studied at Eton. He has attributed his early interest in poetry to the letters he wrote home as a youngster (his collection, Writing Home, 1985, has a darkly comic opening poem that reminisces about such activities) as well as to his longstanding passion for pop music, combined with his first encounter with the contemporary work of Movement poet, Thom Gunn. Alongside the likes of Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis, then, Gunn’s A Sense of Movement – including poems such as ‘Elvis Presley’ and ‘On the Move’ – went on to become Williams’ earliest poetic model, and his first collection, Symptoms of Loss, is full of the hardy realism and lyrical, crafted formalism of their influence. The book also contains – albeit minimalist – poems of subtle gestures and conceits, as in the ‘smile / [that] is the official seal on my marriage’ in ‘The Butcher’, or the existential doubts of ‘Point of Return’, in which the narrator muses how ‘in the end I treat / Uncertainty as life, / Arrival as defeat.’ But even at this early stage in his career, Williams’ poems reveal a certain uneasiness, wary of writing what he has called ‘tip-of-the-iceberg poems’; ‘the mesh too gross / for explanations // […] as words / Go crashing down among the clowns’, as he puts it in ‘The Net’.

His following collections, then, including Sugar Daddy (1970), Some Sweet Day (1975; named after the Everly Brothers' song) and Love-Life (1979) represent a gradual move away from the taut, austere aesthetic associated with minimalists such as Ian Hamilton and Colin Falck, towards the relaxed writing of Williams’ maturity which, perhaps surprisingly, is fresher, more candid, and increasingly more direct in its tone and impact. While succinct, for instance, ‘A Letter to My Parents’ from Writing Home flickers on the borderline between poetry and prose:

There is quite a lot of news from this front.

I got hit in the face, but I am all right now.

How are you? How is the play?

A little dog called Bobby ran out into the road

and was run over by a car.

I am sorry this is in pencil, but I am upstairs

lying down.

The subtle music of Williams’ work, however, ensures that even at his most prosaic there is poetry to be found: the poem condensing the various events and lessons that make up the schoolboy narrator’s life into something disparate, subtly ambiguous and almost nonsensical, as the reader is made aware of the physical, but also personal and emotional, distance between parent and child. What the poet and critic Mick Imlah has called ‘a classic of creative autobiography’, Writing Home’s poems also demonstrate Williams’ understanding of poetry as inventive performance and deceptive verisimilitude, including enticing insights into the poet’s actor-father’s demeanour and character: ‘“You should be with someone / a full minute,” said my father, / “before you realise they are well dressed.”’

Self-Portrait with a Slide was published in 1990. It features one of Williams' best-known poems, ‘When I Grow Up’, which in his own words is ‘couched as a prayer to cheer God up’, consisting as it does of a list of varying ailments that the young narrator curiously wishes upon himself: ‘I promise I’ll be good / if you let me fall over in the street / and lie there calling like a baby bird.’ In many ways, the poem is paradigmatic of Williams’ more admirable poetic qualities: the openness, the pitch-perfect tone and humour, the gentle self-deprecation and the appealing lack of self-importance; virtues that have motivated some critics to label Williams as ‘a truth-teller’. However, while his distinct lack of irony is certainly beguiling and refreshing (especially in an era when poetic obfuscation and allusiveness have long been staples), the more theatrical and imaginative elements of Williams’ poetry make this seem like an oversimplification. For instance, in his collection, Dock Leaves (1994), ‘Prayer’ sees the poet wishing for ‘the strength to lead a double life’, and Williams’ paradoxical shuttling between entertaining artifice and frank sincerity seems exactly the feat he’s always tried – and on the whole succeeded in – getting away with.

Williams’ most successful collection to date, though, is undoubtedly Billy’s Rain (1999), a sensational chronicle of a drawn-out love affair that won the T.S. Eliot Prize. A series of poems on absence, missed opportunity and regret, the rain of the book’s title poem is the sort used in film as an alternative to genuine rain’s failure to show up on camera; a fruitful metaphor for poetry’s special effects, restrictions, and what Sian Hughes described in the Times Literary Supplement as ‘a reference to the secret code of communication used between two people’. Such comparisons between film and poetry are particularly apt in a poetic that is so often cinematic, Williams’ own mantra being to ‘keep it simple and make it visual’.

Despite the accomplished and charming nature of poems such as ‘The Lisboa’ and ‘Strange Meeting’, however, Williams work – and Billy’s Rain in particular – has met with resistance and firm criticism in some quarters. Robert Potts has even gone so far as to describe him as a ‘one-club golfer’, ‘a charming and stylish prose writer [whose] poems don’t think hard [nor] encourage anyone else to’, and it is possible to hold some sympathy with this verdict when one considers the narrow thematic scope of Williams’ work. Dear Room (2006), Williams’ latest collection, may be poised and engaging in its tone and delivery, for instance, but in dealing with familiar themes of love, loss and separation it offers little in the way of surprises. Where aspects of his work may bear certain flaws, however, it would be absurd to apply such criticism to the full range of Williams’ poetry to date. A recent poem published in Poetry Review, for example, sees a return to Self-Portrait with a Slide’s ‘Sonny Jim’, a sort of theatrically debonair version of Weldon Kees’ Robinson whose fictional, alter-ego characterisation fits perfectly into and invigorates Williams’ writing style.

However Williams’ poetry develops, though, one thing seems certain: it will remain in tandem with his longstanding, thought-provoking and often humorous ‘Freelance’ column in the Times Literary Supplement (selections having been collected in Freelancing: Adventures of a Poet,1995), which for years has brightened the pages of that resolutely academic journal, much as his poems serve to do in the occasionally austere world of poetry.

Ben Wilkinson, 2008