- ©

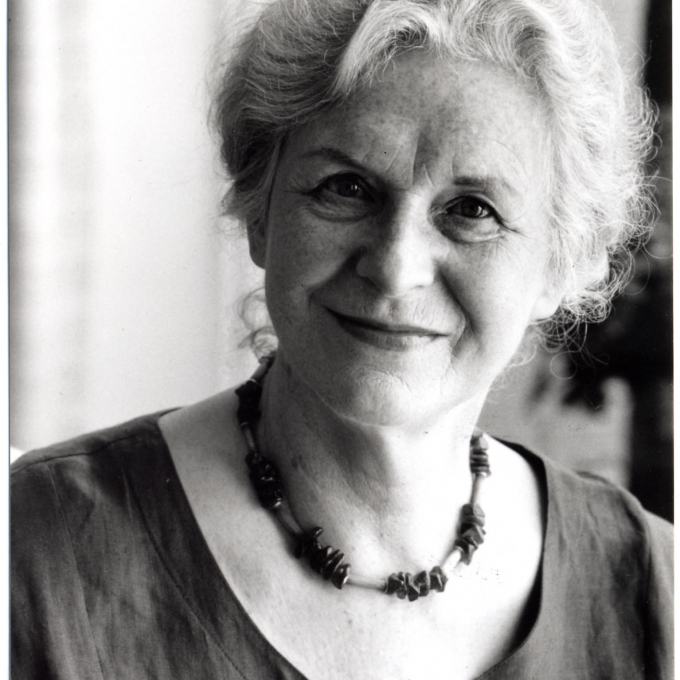

- Julia Hedgecoe

Biography

Professor Dame Gillian Beer was the King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at the University of Cambridge from 1994 until her retirement in 2002 and is a former President of Clare Hall College. She is now Emeritus Professor and an Honorary Fellow of Clare Hall and Girton Colleges. She was Andrew W Mellon Senior Scholar at the Yale Center for British Art from 2010-2012.

She is a Fellow of the British Academy and of the Royal Society of Literature, and is a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the American Philosophical Society. She was made a Dame in 1998. She has twice been a judge for the Booker Prize, the second time as Chair, and has been on the board of the Writers' Centre, Norwich and Arts Council England East. She is President of the British Association for Literature and Science and General Editor of Cambridge Studies in Nineteenth Century Literature and Culture.

Among her books are Darwin's Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot and Nineteenth-Century Fiction (1983, third edition 2009), Open Fields: Science in Cultural Encounter (1996) and Virginia Woolf: the Common Ground (1996). She has published a series of essays on rhyme and a collected and annotated edition of Lewis Carroll’s poems, Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense (2012). Her Alice in Space: the Sideways Victorian World of Lewis Carroll appears from Chicago University Press in 2016.

Critical perspective

If, as C. P. Snow argued in 1959, literature and science have become two separate cultures, then it could be said that Gillian Beer’s primary achievement as an academic and writer has been to restore the links between them.

Though she began her career as a theorist of the romance, a background which provided insightful readings of Jane Austen and George Meredith, her driving interest has always been in the historical and cultural contexts of the English novel, and specifically, the relationship between literary narrative and modern scientific thought. In confronting the latter, she insists on an almost forensic attention to language. "We need to learn the terms of past preoccupations", she argues, "to experience the pressure within words, now slack, of its anxieties and desires" (Arguing with the Past, 1989).

Beer’s commitment to pursuing the complex interface between scientific and imaginative worlds was the impetus for Darwin’s Plots (1983), her pioneering study of evolution as a theme of the nineteenth-century English novel. She launches this work with the suggestion that scientific theories themselves begin as forms of fiction, hypotheses which must then be absorbed not only by scientists but all the inhabitants of a culture. And in this process of absorption, the Victorian novel played a crucial role, filtering and redrafting the currency of Darwinian ideas for a general readership. Just as the author of The Origin of Species (1859) struggled to find language adequate to "a new story", so did the key writers of the time – Charles Kingsley, George Eliot and Thomas Hardy – revise the terms, structures and devices of nineteenth-century realism in order to accommodate in their fiction the impact of Darwin’s revolutionary discoveries.

In her profile of the Victorian age, Beer insists that the effects of evolutionary research were felt by society as a whole, and experienced far beyond those individual writers who actually read Darwin or his fellow scientists, Lyell and Huxley. Moreover, the relationship between literary and scientific communities was closer in the nineteenth century than in the present era: writers responded to scientists and scientists drew, simultaneously, on literary or philosophical texts for their arguments, leading to a fluid exchange of ideas and frequently to what Beer calls the "creative misprision" of scientific material. Thus, Darwin’s own prose style, with its "apparently unruly superfluity of material gradually and retrospectively revealing itself as order" can be seen to owe a good deal to Dickens, while novels of the later Victorian period display a distinctly evolutionary vocabulary in the use of terms such as 'generation', 'struggle', 'variation' or 'inheritance', together with a pattern of scientific reference in their organisational structures. Above all, as Beer illustrates best in her brilliant analysis of George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871-2), imagery and metaphor – the mainstays of the novelist’s trade – become infused and transformed with the significance of scientific meaning.

Given their affinities to each other as intellectual women writers in a predominantly masculine arena, it is not surprising that George Eliot provides a key focus for Beer. In her 1986 study of Eliot, she applauds the novelist’s ability to write specifically, as a woman and universally as a human being. Her sensitivity to Eliot’s position on issues of sexuality, gender and literature is also evident in a telling essay from her book Arguing with the Past, in which she twins Eliot with her other literary heroine, Virginia Woolf. Both, she argues, were obliged to deal strategically with a patriarchal determinism; both, as Beer puts it, "wrote askance from the expected rather than confront it".

Like Eliot, Woolf has remained a long-term source of fascination for Beer. In 1996 she published a book of essays, The Common Ground, in which she tackled the intellectual contexts of Woolf’s fiction, expanding further than any previous critical readings a sense of this novelist’s resources and capacity. Her study of To the Lighthouse, for example, enlarges on the philosophical allusions made in the novel and its interpretations in the light of Hume and Berkeley; her analysis of Mrs Dalloway and The Waves addresses the foregrounding of the self and its communities in an illuminating study of Woolf’s use of personal pronouns, and, in this book’s much noted final essay, 'The Island and the Aeroplane', Beer conjectures on Woolf’s national sensibility in relation to the changing communities of wartime England.

Predominantly however, Beer’s reading of Woolf is shaped by her enduring critical interest in evolutionary science as a context for creative literature. Her stated intention in this book is to place the writer in a real social landscape. The "common ground" of her title is a means of illuminating Woolf’s response not only to Aeschylus, Shakespeare, Virgil and Dante, but also to a non-literary environment; the fact that instinctively she "picked up lightly the thoroughgoing arguments of historians, philosophers, physicists, astronomers, politicians, and the stray talk of passers-by". Beer sees Woolf as an ironic inheritor of Victorianism and simultaneously as a quintessential modernist, tuned to the rhythms of the everyday, and in particular, to the physical processes of the world around her. In this respect, Woolf too is very definitely a Darwinian, her writing – evidenced here in Beer’s treatments of The Voyage Out and Between the Acts - marked with traces of evolutionary ideas and the narratives of prehistory. Undoubtedly, this scientific version of Woolf, as a female intellectual drawn to theoretical physics as much as the classics, comes close to Beer’s own heart, an affiliation confirmed by her celebratory public lecture in 2000 on the writer, published as Wave, Atom, Dinosaur: Woolf’s Science.

Beer’s accomplishment has been to reintegrate an English literary tradition with a bedrock of scientific thought. While avoiding programmatic or deterministic readings, she has shown the relationship between science and literature to be sustained and influential, charged with a mutually enhancing creativity. This is the interpretative route taken in her analysis of the literary bearings of anthropology, travel narrative, solar physics and even wave theory in her 1996 essay collection, Open Fields: Science in Cultural Encounter, and, in the same year, the critical stance emphasised in her edition of Darwin’s The Origin of Species. Her introduction to the latter pays homage to Darwin not only as a revolutionary scientist but as an artist, a highly creative writer who "allows the reader to participate in a copious world, a voyage into the past as exuberant as his voyage round the world in the Beagle". In much the same way, Beer’s own writing, so groundbreaking in its cross-disciplinary pursuits, successfully leads its readers into new territories, and through what Darwin himself called the "open fields" of history, humanity, imagination and science.

Dr Eve Patten, 2005