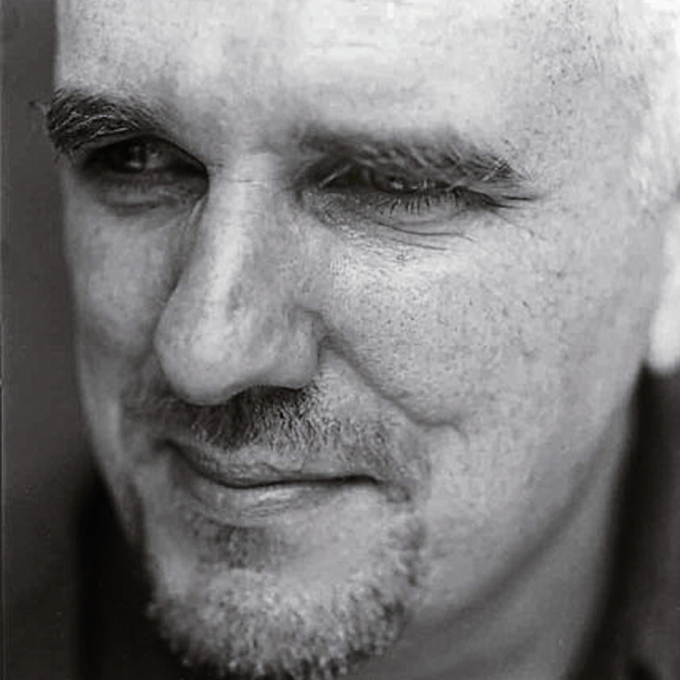

- ©

- Charlie Hopkinson

Biography

Gerard Woodward was born in London in 1961 and studied art and anthropology.

He has published a number of poetry collections, including: Householder (1991), which won a Somerset Maugham Award; After the Deafening (1994); Island to Island (1999); We Were Pedestrians (2005); and The Seacunny (2012).

His first novel, August, was shortlisted for the 2001 Whitbread First Novel Award, and was followed in 2004 by I'll Go To Bed At Noon (2004), shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction. Both novels draw on his own family history, the first telling the tale of a mother's dependency on solvents, and the second being about a brother who is a gifted musician. The third novel in the trilogy, A Curious Earth, which also focuses on the Jones family, was published in 2007.

Gerard Woodward is a regular reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement and the Daily Telegraph, and lives in Bath, where he lectures in Creative Writing at Bath Spa University College. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His Jones family trilogy was followed by a collection of short stories, Caravan Thieves (2008), and the novel, Nourishment (2010), set in wartime London. Vanishing, a novel which explores ideas of camouflage, costume and concealment through a wide range of subjects, was published in 2014.

Critical perspective

Gerard Woodward’s latest poetry collection, We Were Pedestrians (2005), further develops his longstanding imaginative preoccupation with houses, domestic objects and family life.

Alongside poems inspired by his parents and his children (‘the little storm of their playing’), however, there’s a science fiction view of humanity that seems peculiar to him. This is exemplified by ‘Ecopoesis’, a remarkable sequence about the future colonization of Mars that envisions the planet as having been made into ‘one vast room, world-sized, / Near whose ceiling two acorn / Moons float. Sofa hills. Lamp stand mountain’. Captured asteroids are ‘Wandering lamely like demented / Children in trouble with their guardians / And dressed in torn frocks of ice’. Such lines also signal that rooms - and demented children - loom large throughout his poetry and fiction. Woodward’s vision of domesticity is distorted and often troubled; what he has called ‘manipulations of dwelling spaces’ is an essential theme. More recently he has been acclaimed for a trilogy of blackly humorous novels about the self-destructive Jones family: August (2001), I’ll Go to Bed at Noon (2004) – short-listed for the Whitbread First Novel Award and Man Booker Prize for Fiction respectively - and A Curious Earth (2006). Taken together, they movingly capture the grotesque excesses of human behaviour, and what Rachel Cusk has called ‘not only the memory and change that make up the history of a family, but also the flavour of modern Britain’.

Woodward is a poet of extraordinary views, and ‘Ecopoesis’ is a reminder that he began writing in the style of Craig Raine’s then-fashionable ‘Martian School’, making familiar objects unfamiliar by exotic similes and metaphors. (Woodward was also influenced by Peter Redgrove, and by studying painting and anthropology.) So, in his first collection Householder (1991), domestic appliances take on a life of their own, such as the ‘Gas Fire’: ‘the sea exhales / into our living room. // I make his breath visible/ with matches’. ‘The Kettle’s Story’ becomes a metaphor for death and resurrection: ‘His hat is brimming with ideas, / He can’t keep them in / …. He has to shout like an evangelist’. But, with hindsight, the most significant poems are those that allude to family members. ‘Garlic Walk’ asks of his brother: ‘Was it the drink that made him play/ the piano with his fists/ Or the garlic’. And, in an elegiac poem, ‘My mother’s lap // Is a lap of ash already / As she slowly burns away’ (‘Smoker’).

After the Deafening (1994) continues with the domestic theme: amidst decaying houses, there is the perception that ‘the commonplace can suddenly / Be red hot’ (‘A Cook’s Warning’). The mood is often surreal and dream-like, in poems such as ‘Oranges’, ‘The Knowledge’ and ‘Sleeping Partners’. ‘Black Comedy’ sounds a note of suppressed anguish, ‘As if Mum’s // Death had made us all / Foreigners, and the funeral / Had been a sketch that had us/ Killing ourselves’. Such disturbed dreams and memories build up towards a frightening pitch as the book closes: ‘That night the house / Troubled the householder’s sleep / And became a kind of Wolf Rock’, and ‘an ordinary suburbia / Changed to black, frightening sea’ (‘Lighthouse’). Island to Island (1999) is a less highly charged volume, yet still strange in its visions: of ‘Furnishings’ on the moon (‘Arranging Hepplewhites for a parliament of dust’), taxis flowing ‘like treacle’, and oblique autobiographical asides: ‘our lives / Were at right angles to other children’s’.

It is as a novelist that Woodward is best able to choreograph his disturbing domestic visions, with eccentric characters moving through episodes of love and loss, despair and partial redemption. The three novels tell the story of the Jones family – parents Aldous and Colette, their children Janus, James, Juliette and Julian – from 1955 to the 1980s, with passion, compassion, and a keen eye for the absurd. Alcoholism, addictions and self-harm over the years come to affect all of the family. Their lives, certain events in the changing society around them, take place in Wales and the North London suburbs. August covers the years from 1955 to 1970, its title referring to the annual holiday month of the Jones’s. At its opening, art teacher Aldous is knocked off his bike and discovers an idyllic holiday place for his growing family. But the story is ever-darkening, especially his relationship with his wife Colette and eldest son Janus, musically gifted but increasingly erratic. These conflicts form the tragedies to come, while youngest son Julian becomes the observer of the family’s disintegration. By 1965, Janus is studying at the Royal College of Music, but thinks ‘it is my vocation to cause you pain to counterbalance the pleasure you had in conceiving me’. Heavy smoker Colette starts sniffing glue, has hallucinations, and is temporarily taken into a mental hospital. Janus’s drunken behaviour is now obsessive and violent. By 1970, the despairing Aldous feels that ‘the house is broken’, and dreams that it ‘billowed and ruffled like a tent in a storm’.

I’ll Go to Bed at Noon is the most harrowing of the novels, its upheavals and bitterness paralleling events in Britain during the 1970s. Aldous has rediscovered his vocation as an artist, but is angry at Janus’s ‘wanton neglect of his talents as a pianist’ and living in fear of his son’s demands. Colette has recovered but having to care for her brother, who is suffering from dementia and drinking himself to death. For him, memory is ‘like an illness … it was corrosive, malignant’. Janus is now on a doomed spiral downwards, and continues to torment his parents, while Julian ‘realised the house was more frightening when it contained people’. Aldous himself starts drinking heavily, and recites from King Lear: ‘a poor old man, as full of grief as age’. Left almost alone at the end of the novel, he realizes that, aged 67, ‘he had more time than he knew what to do with’.

The Curious Earth (2006) takes the story into the mid-1980s. The family house has ‘the ear-pounding silence of a house vacated by all-but-one’. Widower Aldous is now the main character, jolted out of his despair when he ends up in a geriatric ward. Art provides his escape; he fills his life with a great interest in Rembrandt, and meets a younger woman at an evening class. For Aldous, ‘it was as though he’d fired a starting pistol on the rest of his life’, and he travels to the continent for the first time in years. As in the other novels, amidst the despair there are some wonderfully tragic-comic descriptions, for instance of a rough Channel crossing, and the goings-on at a bohemian party. Aldous’ final desire is to turn his house into an art gallery, a project that brings what is left of the family together. Aldous’s conclusion is that ‘tragic is much better than sad. I’m happy with tragic’. Woodward’s disconcerting vision of family life - as both a novelist and poet – allows us to grasp the truth of this statement, and makes his work compelling.

Dr Jules Smith, 2007