- ©

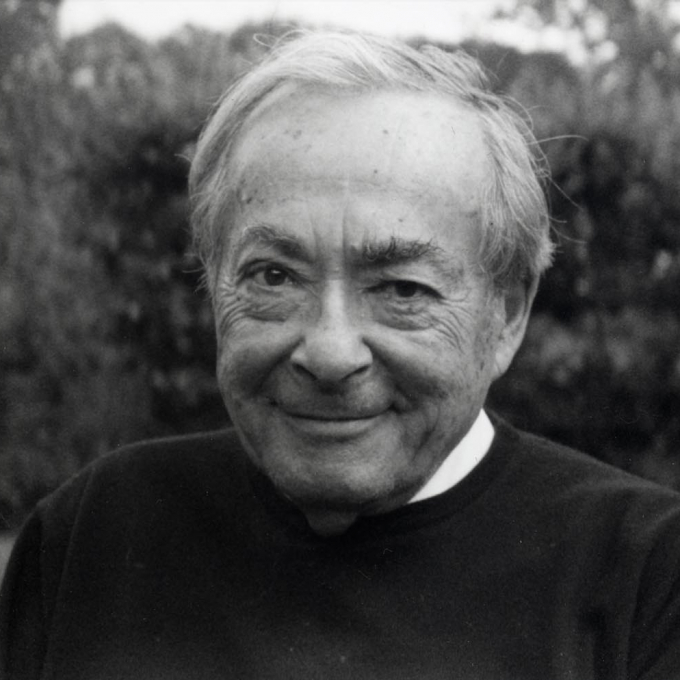

- W M Logan

Biography

Professor George Steiner was born in Paris on 23 April 1929. His family moved to the United States in 1940 and he was educated at the Universities of Paris, Chicago, Harvard, Oxford and Cambridge. He was a member of the editorial staff at The Economist in London during the 1950s before beginning an academic career as a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University in 1956. He was appointed Gauss Lecturer at Princeton in 1959. He has been a fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge, since 1961 and was Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Geneva between 1974 and 1994.

Professor Steiner has held visiting professorships at Yale, New York University, the University of Geneva and Oxford University. He is an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an honorary fellow of Balliol College Oxford, and has been awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur by the French Government and the King Albert Medal by the Royal Belgian Academy. He received the Truman Capote Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature in 1998 and in the same year was elected Fellow of the British Academy. He is currently Weidenfeld Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Oxford, Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University and Extraordinary Fellow of Churchill College at Cambridge University. His non-fiction includes Tolstoy or Dostoevsky (1958), a critical analysis of the two great masters of the Russian novel, The Death of Tragedy (1961), In Bluebeard's Castle: Some Notes Towards the Redefinition of Culture (1971) and No Passion Spent: Essays 1978-96 (1996). His book on translation, After Babel (1975), was televised in 1977 as The Tongues of Men. He is also the author of a number of works of fiction including Proofs and Three Parables (1992) and The Portage to San Cristobal of AH (1981), which was adapted for the stage by Christopher Hampton. A volume of autobiography, Errata: an Examined Life, was published in 1997. Grammars of Creation (2001) discusses a range of subjects from cosmology to poetry.He is a regular contributor of reviews and articles to journals and newspapers including the New Yorker, the Times Literary Supplement and The Guardian.Professor Steiner lives in Cambridge, England. His latest book is one of memoir, My Unwritten Books (2008). A collection of pieces written between 1967 and 1997, George Steiner at the New Yorker, was published in 2009.

Critical perspective

George Steiner is experienced as a writer in many forms, but he is best known as a piercingly intelligent and shamelessly intellectual critic and essayist.

He is a true critic, not just an occasional reviewer; he is not merely an instantly reactive, insightful reader, but a thinker who develops coherent theories of literature; and he manages to do this using a frame of reference which is quite breathtaking in its scope.There is some straight philosophy, but in the main his non-fiction work is general literary criticism of impressively broad sweep (and miscellaneous essays, reviews for The Observer, etc.). He is able to get to heart of very difficult thinking; the most impressive case of this being his exemplary Heidegger (1978, Fontana Modern Masters series), which takes this most awkward of philosophers and undaunted tackles him with confidence and clarity. It is a well-balanced exposition, but also distinctive - there is quite a lot of Steiner himself to be found in it too.In 1960 he published his combined study of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky: An Essay in Contrast which is more than a simple reading of the texts but engages with the difficult ideas and ideologies of these two fascinatingly different writers. So it can be read as an interesting philosophical and biographical study, even if you've never read a word by either of the Russians.Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky is fairly atypical, however, in that for the most part Steiner's subjects for study are not specific but are rather broad and thematic; among the best of these is The Death of Tragedy, which was published in 1961. Unusually for a work with such a broad sweep across millennia of literature, it maintains a clear and unified thematic treatment of its subject, and has a single main thesis to be made, as he surveys the field from the ancient Greeks to the mid-twentieth century.Some of Steiner's early criticism can be seen as leading up to his magnificent After Babel (1975). This wonderful book is a typically dense study of language and translation, mining his examples from all over the place (geographically and chronologically) and covering huge amounts of ground as he goes. It is extraordinary in making a real contribution to translation studies, while remaining fairly self-contained and accessible to people who have never before given the matter a second thought. As it deals with the problems - linguistic and circumstantial - of translation, it also helps us to think about how we look at language itself. Not only did it chart a great deal of previously uncharted territory - in truth it was the first thorough study of the subject - but also it has still not been surpassed in depth or breadth in the three decades since publication.Steiner has found time to put together a bit of fiction too. There are a number of short stories, all clever and interesting, but none to rival the ambition and execution of his excellent novella, The Portage to San Cristobal of A. H. (1981). It is stronger on ideas (language, evil, guilt) than on characters, certainly, but it is sufficiently extraordinary and extreme, and there is sufficient tension created, to keep it a thrilling read, for all its Old Testament erudition. The premise of the story is that Adolf Hitler might not have died - as is generally believed - in the bunker in Berlin in 1945, but might yet be living somewhere, and might yet be discovered. In exploring the mysterious reappearance of this demonic figure in the depths of the Amazon, thirty years after the end of the war, Steiner deals bravely with dangerous material. He gives Hitler a voice, and words to justify his actions - and his voice is famously compelling, even (or perhaps especially) in its wilder ravings. In Hitler's voice lay his power, and Steiner is not afraid to let that voice speak again. 'His tongue is like no other. It is the tongue of the basilisk, a hundred-forked and quick as flame.'Steiner's best work - this novella included - is prompted by investigations into the power of language, whether this is used to literary ends (it is no accident that his Fontana monograph is on Heidegger, of all philosophers) or marshalled for the perpetration of the greatest evil, as in the case of the Holocaust (the Jewish experience in the twentieth century is one of Steiner's most consistent preoccupations). This is the central concern of his collection Language and Silence (1967); among other things it explores the limitations of language, and the possibility that the only real human response to the atrocities of our age is not literature, with the redemptive powers it has always been assumed to have, but silence. Can we still make 'assumptions regarding the value of literate culture to the moral perception of the individual and society'? Steiner thinks not, and this for him is a cause for the greatest concern.Steiner's own personal responses to the world of the twentieth century are gathered in a 'memoir', but Errata: An Examined Life (1997) is not a conventional autobiography. Although it does indeed inform us about his growing-up years, where he was when and what he did when he was there, its emphasis is on explaining the development of his thinking and interests over the course of his life. So there is little that is entirely new in it, but it does give us a new way of understanding - biographically - the sources of what we have read of his work already.It would do Steiner less than justice to overlook his excellent collection of occasional essays No Passion Spent (1996), which covers subjects as diverse as Kierkegaard, Homer in translation, Biblical texts and Freud's dream theory. Spanning about twenty years, these pieces are united by a common concern for the importance and significances of reading, at this time when new technologies and theory have brought its conventions under threat. The opening essay - 'The Uncommon Reader' - is one of the most gratifying and most accessible. In it Steiner uses Chardin's painting 'Le Philosophe lisant' (used on the cover of the volume) as a starting-point for an exploration of what he calls 'the classic act of reading', as depicted in the picture. He explores all the things that this act properly requires - learning, silence and so on - and the modern threats to it (to learning, to silence) which make it an endangered skill and pleasure. As in all Steiner's work, even the little odds and ends of seemingly trivial occasional writing are sharp and readable - exemplary criticism and exemplary writing. For all his range it is his criticism that is truly the most excellent. It is this that ranks him among the great minds in today's literary world.

Daniel Hahn, 2002