Biography

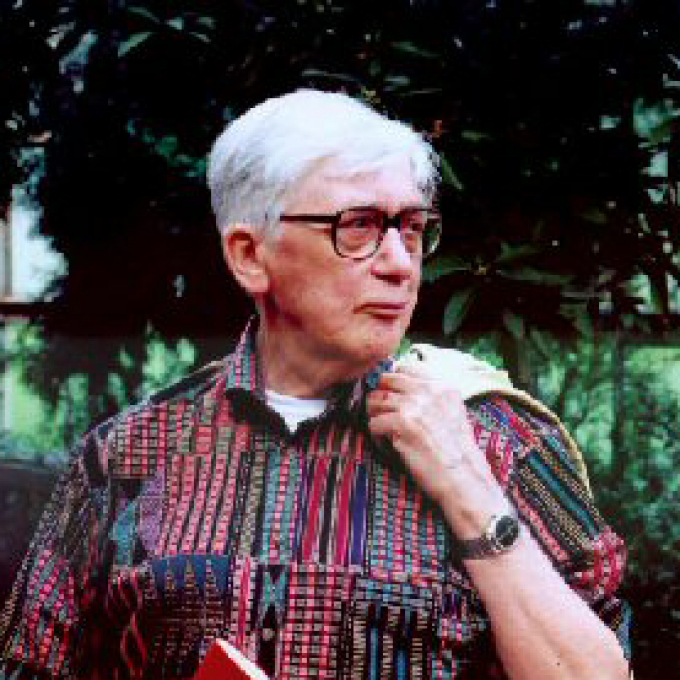

Edwin Morgan was born in Glasgow in 1920, first starting to write while at Glasgow High School.

He studied English at Glasgow University, but his studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He returned to University after the War and graduated in 1947.

From 1947-1980 he taught English at Glasgow University, becoming Professor of English in 1975. During this time time he produced a major body of poetry and critical essays. He also wrote plays, libretti, and several works of translation. He travelled widely after the 1950s and translated poetry from many languages, particularly Russian, Hungarian, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Italian and French. In the 1960s he experimented with concrete poetry and also championed Beat Poetry. His translations included Edmond Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac (1992) and Jean Racine: Phaedra (2000). He translated many poets into Scots including Mayakovsky, Racine and Neruda. In 1996 his Collected Translations were published and his Collected Poems re-published.

In 2000, his first original dramatic work, A.D.: A Trilogy of Plays on the Life of Jesus, was published and appeared on stage in Glasgow.

Edwin Morgan was awarded several honorary degrees and an OBE in 1982. In 2000 he won the Queen's Gold Medal and in 2001 the Weidenfeld Prize for Translation for Jean Racine: Phaedra. He became Glasgow's first Poet Laureate in 1999 and A Glasgow International Writing Festival has been named From Glasgow To Saturn after one of his poetry collections. In February 2004 Edwin Morgan was appointed 'Scots Makar' - National Poet for Scotland.

His collection A Book of Lives (2007), was shortlisted for the 2007 T. S. Eliot Prize, and his last collection, Beyond the Sun (2007), is a series of poems on paintings.

Edwin Morgan died in August, 2010.

Critical perspective

The immense body of work published by Edwin Morgan since 1952 might suggest an imperious project of cultural domination, but no one having the slightest acquaintance with Morgan’s poetry would think so: his writing offers an extremely rare combination of epic scope with lightness of touch.

Such a balance between matter and formal brilliance is very rare, and although the adjective ‘Mozartian’ is perhaps too frequently applied nowadays, Morgan has a claim to it.

More than most poets Morgan seems to extend a genuine invitation to the reader: try this, then in contrast try this, and then try a third thing and so on, all of them obviously the work of a single imagination but at the same time marked by protean diversity of form and subject. To try to describe the clarity of the results, it might be said that Morgan marries the rich formal repertoire of Scots poetry from the Middle Ages onwards with an apparently untroubled openness to the possibilities of modernism.

There appears to be nothing Morgan is not interested in, nothing he considers too small to deserve or too big to lend itself to his attention, no form he will not explore. The author of the Instamatic Poems (1972) cares for the minute detail of the given moment – ‘the striking absence of consternation’ in ‘Glasgow 5th March 1971’, when the man in the dock of the Central Police Court throws a knife at the magistrate; or the man smoking and brooding without enlightenment on the dance of swans on a Suffolk river (‘Ellingham Suffolk January 1972'). This quality of attention is also found in the vast panoramic prophecy of doom in an early masterpiece, ‘Stanzas of the Jeopardy’ (1952), in the beautiful affirmative gay love poem, ‘The Unspoken’ (1968), in his science fiction poems and in the richly playful poem 25 of From the Video Box (1986) ‘If you ask what my favourite programme is’, where a master jigsaw-puzzler takes on his greatest challenge, the Atlantic Ocean. At the puzzle’s completion

'…the saw-lines disappeared,

till almost imperceptibly the surface moved

and it was again the real Atlantic, glad

to distraction to be released, raised

above itself in growing gusts, allowed

to roar as rain drove down and darkened,

allowed to blot, for a moment, the orderer’s hand.'

The return to the world at the close of this poem seems to be a constant priority for Morgan. It is not that art is inferior to the world in which it is produced, but that it should not forget that it belongs there. The problem faced by many poets – that the intricacies of the imagination and of literary inheritance separate the writer from the general audience – seems not to affect him. He manages to write as if his work is intended for everybody without sacrificing its complexity.

The voices of Morgan’s fellow Glaswegians frequently enter the poems. The radio poem ‘The Demolishers’ (1978) intercuts verse commentary with the comments of local residents and workmen on the demolition of Glasgow tenements, as though to demonstrate the intimacy of poetry and speech, and to show that sometimes, as Tom Leonard, a fellow Glaswegian poet, would also affirm, speech has the best lines: ‘Just goany happen, intit’. The harrowing testimony of ‘The Porter’ in ‘Stobhill’, a poem for several voices about the treatment of a foetus mistakenly thought to be dead, consisting of the characters’ continuing efforts to explain or exculpate themselves, is a striking renovation of the Browningesque dramatic monologue and an exemplary instance of the use of ‘ordinary’ speech in poetry. At the bottom of the chain of authority, the porter feels like the scapegoat, and like his daughter’s hamster on its wheel:

'Don’t answer nothing incriminating, says the sheriff.

And that’s good enough for yours truly.

and neither ah did, neither ah did,

neither ah did. Neither ah did.'

The lesson has not been lost on Morgan’s successors, such as Liz Lochhead, W.N.Herbert and Jackie Kay, whose work preserves a live connection between speech and poetry. More generally, in the widespread flowering of Scottish poetry between 1980 and the millennium, Morgan’s benevolent, enabling influence has been frequently apparent.

This is in part the birthright of a poet from a society which is in some respects rather more insistently democratic in its attitudes and expectations than England, The urge to nationhood has retained over the centuries ‘a thread of pride that has been almost but not quite, oh no not quite, not ever broken or forgotten’, as Morgan, the Makar, the Scottish poet laureate, put it in his poem ‘For the Opening of the Scottish Parliament, October 9th 2004’. The expectation is that the governors will take instruction from the nation, and he offers a friendly warning that should the governors displease their electors, ‘you will know about it’. Morgan, of course, has a distinct historical advantage: his role, like the Parliament itself, is both new and old. No modern English laureate could conceive of such a poem or imagine the occasion on which it might be heard. At this early stage, cultural prestige might be said to have a different function in Scotland: it figures as a resource, not a possession to be taken for granted.

The gravity of Morgan’s work is also underwritten by its very playfulness. His excursions into concrete poetry, sound poetry and found poems are undertaken with the same care and skill as the rest of his writing, but he evidently takes a childlike pleasure in the sheer material fact of language in work such as the sound poem (a classroom favourite) ‘The Loch Ness Monster’s Song’ and the series ‘The Horseman’s Word’. It is out of such delight, we infer, that there has grown the rich seriousness of his writing as a whole. A university teacher for many years, Morgan is also an educator in his poems – one who, by example rather than insistence, points the way to life’s possibilities.

A great deal more could be said of Morgan’s work without even touching on his equally productive and distinguished career as a translator from many languages, which locates him in the proud tradition of Scottish internationalism; or his activities as a playwright and librettist; or his essays and criticism. Suffice it to say that, for the reader, the rewards of his writings are as prodigious as their scale.

Sean O’Brien, 2007