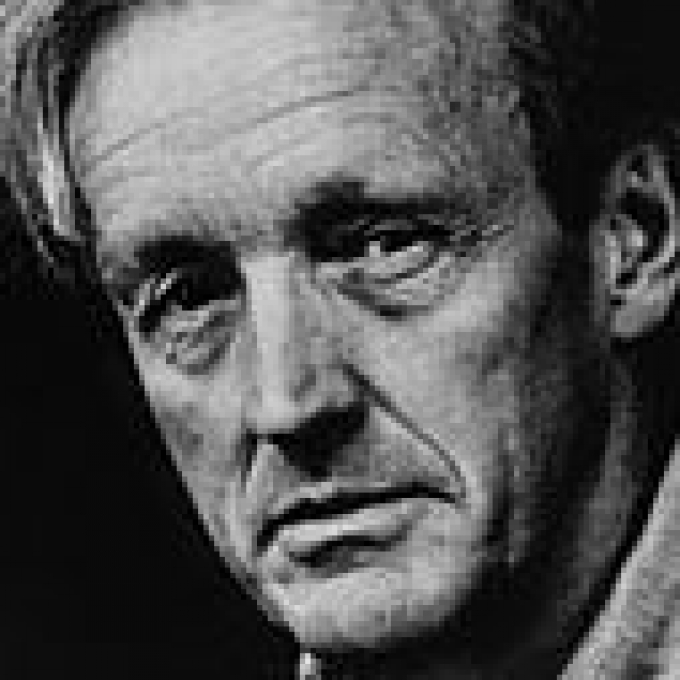

Colin Thubron

- London, England

Biography

Award-winning travel writer and novelist Colin Thubron was born in London on 14 June 1939. Educated at Eton College, he worked briefly for the publishers Hutchinson and as a freelance television film-maker in Turkey, Japan and Morocco. His first book, Mirror to Damascus, was published in 1967. He continued to write about the Middle East in The Hills of Adonis: A Quest in Lebanon (1968) and Jerusalem (1969).

Among the Russians (1983) describes a journey he made by car through western Russia during the Brezhnev era. Behind the Wall: A Journey through China (1987) won both the Hawthornden Prize and the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award. The Lost Heart of Asia (1994) narrates his travels through the newly-independent central Asian republics, exploring the effects of the collapse of the Soviet Union on the region. He returned to Russia for his most recent travel narrative, In Siberia (1999).

Colin Thubron is also the author of several novels, including a historical fiction, Emperor (1978), set in A.D. 312; A Cruel Madness (1984), winner of the PEN/Macmillan Silver Pen Award; Falling (1989); Turning Back the Sun (1991), a haunting tale of love and exile; and Distance (1996). To the Last City (2002) tells the story of a group of travellers in Peru, while Night of Fire (2016) is a metaphorical novel in which the inhabitants of one house - perhaps representing the parts of one person's soul - are trapped in a housefire.

A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature since 1969, Colin Thubron is a regular contributor and reviewer for magazines and newspapers including The Times, the Times Literary Supplement and The Spectator. He lives in London. His latest travel books are Shadow of the Silk Road (2006), an account of his 7,000-mile journey along the route of the Silk Road; and To a Mountain in Tibet (2011), about his pilgrimage to sacred Mount Kailas.

Critical perspective

Colin Thubron divides his writing between two genres: travel books and novels.

In the twenty-first century, westerners travel more widely than ever before - Egypt, Thailand, Mexico, the Caribbean, the Maldives – we have 'civilised' and packaged whole areas of the world which are sold off to holiday makers. Yet, there are huge areas on this planet that, because of fear of ideological extremism, or the physical difficulty of travelling, westerners are nervous of visiting. It is these areas: Russia, including the far-flung extremities of Siberia, the Middle East, China and Central Asia, that Thubron explores and reveals to us in his rich, scintillating and utterly captivating prose.

There are four main factors that make up a new environment: its history, its geographical and natural characteristics, its human edifices and its people. Although he only ever refers indirectly to the preparations he makes for his journeys, it is clear that Thubron plans them with religious care, learning the language (Russian and Mandarin Chinese, for example), doing extensive geographical and historical research, collecting names, pre-departure, of people to visit and (despite the seemingly casual way he hops on planes, boats, trains and buses or into his Morris Marina), meticulously planning his route. His historical descriptions, based on his research, are often peppered with dates and abounding with astonishing detail – physical or psychological portraits of the protagonists, statistics such as the number of dead in a particular battle or death camp. They give an extra depth to the narrative, make us aware of how history can mould the character of both a race and a landscape, and, at the same time, convince us of Thubron’s integrity. His descriptions of nature are particularly fine. Two of my favourites, alas too long to quote here, are of a birch wood near Moscow 'a dense audience of silver trunks and thin leaves which dimmed and glistened under a filtered sun', and a disused uranium mine and work-camp in Siberia, where a deserted expanse of snow becomes a potent symbol of physical and psychological desolation.

Thubron is obviously something of a botanist and his descriptions are rich with the names of trees and flowers: silver birches, beeches, cornflowers, hollyhocks, lupins, larkspur, borage, white harebells, poppies and gladioli are just some of many that come to mind. In this, perhaps, he is betraying a very British characteristic, for he comes from a nation of scientists and dilettantes going back to the Elizabethans and Victorians, who have long sought to classify and catalogue nature. Yet, at the same time, Thubron’s categorisation also seems to stem from a typical traveller’s need to see the familiar in the unfamiliar, to name, and hence create order.

Thubron’s descriptions of human edifices range from the various hotels and campsites he stays in to cities, private houses and public buildings. Places of worship and graveyards are, of course, the physical testimony of how a society thinks, and he spends much of his time wandering around churches, mosques and synagogues as well as burial grounds, mausoleums and tombs. But Thubron, the ever-acute observer, also favours institutions, such as schools, hospitals, prisons, mental asylums, seminaries and public bath-houses as places that epitomise a society’s values. As well as the homes of people he meets, he also frequents restaurants, shops, (toyshops seem to have a particular fascination as gauges of social decadence), artists’ studios and a marriage introduction bureau, not to mention the Chinese chemist he visits with a mild stomach-ache, and from which he gingerly exits with a bottle of frog-essence.

Thubron’s descriptions would still be brilliant, but sterile, were they not populated by an amazing collection of characters, sometimes ridiculous, sad, innocent, fanatical, cynical, sinister or noble, but just as often normal, with a surprising disregard for political or religious dogma. He is fascinated by physiognomy and spends much of his time trying to categorise the national characteristics of the various faces he sees. Korvus - who had been Turkmenistan’s Minister of Culture and a well-known poet under the Soviet Administration - is just one example, but there are countless others gems of physical and psychological description. Now, after the fall of Communism, Korvus lives in a somewhat confused state with his son, a liberal film-director, who collects Turcoman artefacts (a hobby that would have been outlawed in Communist times). Korvus is a plethora of contradictions. 'He was an old man. Beneath a burst of white hair his face shone heavy and crumpled, and his eyes watered behind his spectacles… Authority still tinged his stout figure as he greeted me. He wore an expensive Finnish suit and a gold ring set with a carnelian. Yet a Turcoman earthiness undermined this prestige a little, and a loitering humour.'

A gentle sense of comedy is never far from the author’s mind. Who could possibly forget the enthusiastic innocence of the Russian who wanted to buy a pair of Thubron’s jeans? 'He seized them and dashed into a nearby camping hut to change. A moment later he emerged encapsulated in jeans and gasping with triumph like one of Cinderella’s ugly sisters who had fitted the slipper. Where the jeans began, his whole body tapered away like a tadpole’s, while above them his chest bloomed in a monstrous burst of held breath and pigeon ribs. He looked terrible. "Wonderful", he said, "perfect."'

Yet, proficient descriptions would be futile without psychology, and Thurbon does not disappoint us when it comes to human emotion. His own moods are honestly recorded and range from excitement, affection, wonder (at the sheer size of Siberia, for example), through disappointment and indifference (on seeing Lenin’s tomb), to dislike ('I could not like her at all' he admits of a contact in Moscow who invites him to tea), sadness and horror (at the number of dissidents killed in the gulags, to name just one of many instances), disgust (when a self-appointed guide (male) kisses him on the lips, or when he thinks he might be called on to raise a toast to Stalin), and near terror (when he is followed by the KGB in Kiev). He travels solo and often recalls moments of homesickness and desolation that somehow make both him and his books all the more humane and credible. Like many travellers, Thubron tries to remain tolerant and open-minded, yet he sometimes becomes aware of, and is ashamed by, the fact that he observes with a certain western arrogance or pedantry. He is also frequently embarrassed by the generosity shown towards him by those who have so little to give.

The people in the countries he visits on the other hand seem to regard him with bemusement: why is he alone? Where is his group? Why hasn’t he got a wife? Why is he there? He is often aware of how ridiculous he must seem to others. Whilst nude in a Chinese bath-house he encounters an old man. 'When he caught sight of me, his hand had been extended to grasp a mug of tea, but now it remained outstretched before him in a meaningless semaphore, while he froze bolt upright and stared. Could this foreign body be real – white, hairy (comparatively) and mosquito-bitten?' Essentially, it is Thurbon’s own insecurity, emotion and humanity, as much as his inquisitiveness, that make him a great travel writer.

Thubron’s interest in the human psyche continues in his novels, but whereas in the travel books we get tantalising insights into the psychology of races and isolated individuals, the novels give Thubron the possibility to develop his characters more fully. Whereas in his travel books he is interested in how an individual is moulded (or not) by his race and political environment, in his novels is he more concerned with how individuals react within microcosms of society, what he himself calls 'miniature universes'. A Cruel Madness (1984), for example, is set within the stifling confines of a preparatory school for boys and a mental asylum; Emperor (1978), about the Roman Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 AD, is also a study of life in a Roman army on the move and of the Emperor’s court within this. The main characters in Distance (1996) too, act out their story against confines of an academic research institute.

Thubron’s book To the Last City (2002), longlisted for the Booker Prize, is his first to combine his interest in travel with novel-writing. It is a study of a group of five Europeans: an elderly Belgian and his younger wife, a British couple and a Spanish seminarian, who set off, hopelessly ill-prepared, with a guide and some muleteers, to explore the ruins of the Inca city of Vilcabamba. The “cloud forests” of the Peruvian mountains are an inspiring backdrop for the novel, but the landscape is no longer the main focus, as it is in the travel books, and the descriptions are more sketchy, though no less effective. It soon becomes clear that each character, his or her moods closely affected by the environment in which they are travelling, is searching for some sort of psychological outcome from the journey. Francisco, the seminarian, is seeking to atone for centuries of Spanish imperialism, the British couple have come to a watershed in their lives and relationship – she has to cut herself off from her teenage son, he has to face the fact that he is a hack journalist – and the Belgium, an ex-architect, is escaping from a forced redundancy. Only his wife, the pretty, spoilt Josiane seems to have few ulterior motives, yet, with delicate brushstrokes, Thubron builds up an overpowering sense of foreboding as the Inca landscape seek in her its final reparation.

Thubron is not always an easy writer to read. His work is erudite, heavily layered and closely compacted: reading him is more like eating a rich meal than a light snack, but, to follow the eating metaphor, he provides delightful flavours and worthwhile nutrients, food for the mind, that satisfies long after the meal is finished.

Amanda Thursfield, 2003

Bibliography

Awards

Author statement

'My travel books spring from curiosity about worlds which my generation has found threatening: China, Russia, Islam (and perhaps from a desire to humanise and understand them). The novels seem to be reactions against this, and mostly arise from more introverted, personal concerns: often being set in enclosed places (a prison, a mental hospital, an amnesiac's head). My writing swings between the two genres.'