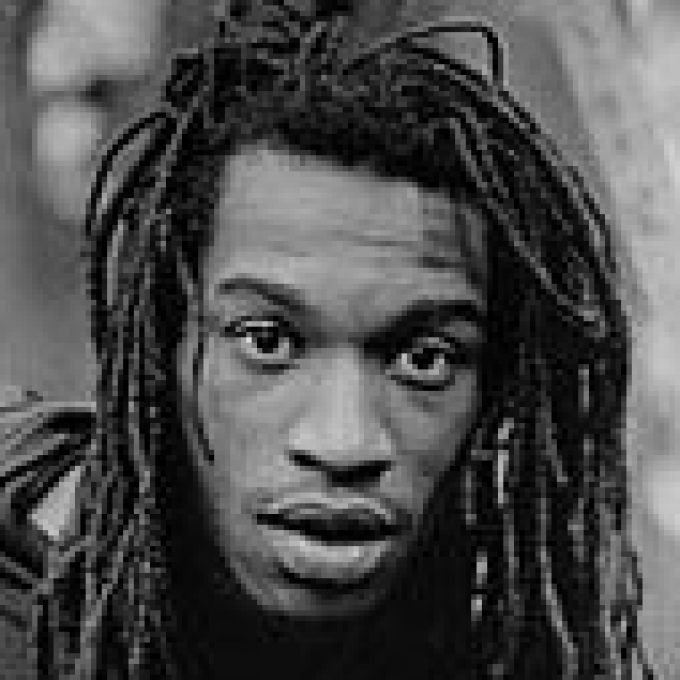

Benjamin Zephaniah

- Birmingham, England

Biography

Poet, novelist and playwright Benjamin Zephaniah was born on 15 April 1958.

He grew up in Jamaica and the Handsworth district of Birmingham, England, leaving school at 14. He moved to London in 1979 and published his first poetry collection, Pen Rhythm, in 1980. He was Writer in Residence at the Africa Arts Collective in Liverpool, and was a candidate for the post of Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. He holds an honorary doctorate in Arts and Humanities from the University of North London (1998), was made a Doctor of Letters by the University of Central England (1999), and a Doctor of the University by the University of Staffordshire (2002). In 1998, he was appointed to the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education to advise on the place of music and art in the National Curriculum and in 1988 Ealing Hospital in London named a ward after him.

His second collection of poetry, The Dread Affair: Collected Poems (1985) contained a number of poems attacking the British legal system. Rasta Time in Palestine (1990), an account of a visit to the Palestinian occupied territories, contained poetry and travelogue. His other poetry collections include two books written for children: Talking Turkeys (1994) and Funky Chickens (1996). He has also written novels for teenagers: Face (1999), described by the author as a story of 'facial discrimination'; Refugee Boy (2001), the story of a young boy, Alem, fleeing the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea; Gangsta Rap (2004); and Teacher's Dead (2007).

In addition to his published writing, Benjamin Zephaniah has produced numerous music recordings, including Us and Dem (1990) and Belly of de Beast (1996), and has also appeared as an actor in several television and film productions, including appearing as Moses in the film Farendg (1990). His first television play, Dread Poets Society, was first screened by the BBC in 1991. His play Hurricane Dub was one of the winners of the BBC Young Playwrights Festival Award in 1998, and his stage plays have been performed at the Riverside Studios in London, at the Hay-on-Wye Literature Festival and on television. His radio play Listen to Your Parents, first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2000, won the Commission for Racial Equality Race in the Media Radio Drama Award and has been adapted for the stage, first performed by Roundabout, Nottingham Playhouse's Theatre in Education Company, in September 2002.

Many of the poems in Too Black, Too Strong (2001) were inspired by his tenure as Poet in Residence at the chambers of London barrister Michael Mansfield QC and by his attendance at both the inquiry into the 'Bloody Sunday' shootings and the inquiry into the death of Ricky Reel, an Asian student found dead in the Thames. We Are Britain! (2002) is a collection of poems celebrating cultural diversity in Britain.

He has recently been awarded further honorary doctorates by London South Bank University, the University of Exeter and the University of Westminster. Recent books include two volumes autobiography, Benjamin Zephaniah: My Story (2011) and The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah (2018, shortlisted for the Costa Biography Award), and further books for children, When I Grow Up (2011) and Terror Kid (2014).

Critical perspective

Benjamin Zephaniah’s background seems unlikely for a poet: a dyslexic who left school unable to properly read and write; a black British Brummie whose teenage years of petty crime culminated in a prison spell.

However, Zephaniah has ended up the people’s poet. Today he holds a handful of honorary degrees. In 2008 he appeared in The Times list of top 50 post-war writers.

Zephaniah’s work is often described as dub poetry, a form of oral performance poetry that is sometimes staged to music and which typically draws on the rhythms of reggae and the rhetoric of Rastafarianism. His poems are often inspired by political causes. Zephaniah has said that he ‘lives in two places, Britain and the world’, and his collections highlight domestic issues from institutional racism (Too Black, Too Strong, 2001) and the murder of Stephen Lawrence to conditions in war-torn Bosnia, the plight of occupied Palestine (Rasta Time in Palestine, 1990) and global environmental issues (see, for example, Talking Turkeys, 1994).

Unexpectedly perhaps, for a poet associated with protest literature, many of Zephaniah’s poems are tempered by hope, humour and laughter. For example ‘I Have a Scheme’, a parody of Martin Luther King’s famous Civil Rights speech of 1963, dreams of a world 'When all people, regardless of colour or class, will have at least one Barry Manilow record'. Parody is one of Zephaniah’s trademark devices. In his collection Propa Proaganda (1996), ‘Terrible World’ plays on Louis Armstrong’s ‘Wonderful World’, and opens with the words: ‘I’ve seen streets of blood …’. ‘Heckling Miss Lou’ on the other hand presents a playful dialogue with the pioneering performance poet Louise Bennett. If such poems seem to trivialize politics, this is arguably to neglect Zephaniah’s sense of the political. He has said that ‘[i]t’s a hard life being labelled "political". It seems that because I’m constantly ranting about the ills of the world I’m expected to have all the answers, but I don’t, and I’ve never claimed to, besides, I’m not a politician. What interests me is people.’ The political function of laughter in bringing different people together cannot be overestimated within this context.

Many of Zephaniah’s poetry collections are written specifically for children (Talking Turkeys and Funky Chickens, 1996), and he has recently written a number of very successful novels for young people. Face (1999) is a set in London’s multicultural East End, but its focus is on a white character, and of one boy's struggles to face his badly disfigured body following an accident. Martin is largely indifferent to the black culture that surrounds him on the streets of the city, but after getting caught up in a joyriding accident that causes terrible burns to his face, he starts to see the world differently. As Martin becomes sensitized to the prejudices of others, and finds himself othered, he starts to connect afresh with those around him, black and white.

The book was inspired by an incident when Zephaniah came face-to-face with Simon Weston, a veteran of the Falklands who was facially-disfigured during the war:

'I was so taken aback by his face. I remember staring and feeling guilty afterwards - I know what it's like if I go to some villages around Britain where they don't see that many black people. I walk into a shop and people look at me, or I walk in the park and get three or four kids gawping. I thought I should know better. I wasn't being nasty to him, it was just seeing somebody who looked so different.'

In his highly regarded second novel, Refugee Boy (2001), Zephaniah tackles the theme of political asylum. Alem, the novel’s Ethiopian protagonist, thinks he is taking a brief holiday with his father in London. Everything is magical in the capital until he wakes up one day and discovers his dad has deserted him. Gradually, through a series of letters, he learns they are not on vacation at all, but fleeing the political situation in Ethiopia.

In his next book, Gangsta Rap (2004), we follow the downward trajectory of Ray, a disaffected teenager who falls out with his family, and is excluded from school before finding fame and fortune in a rap band. If Ray’s life seems to have changed immeasurably for the better, it is not long before his problems resurface and he is caught up in shootings and gang rivalry: an unsavoury underworld of male violence that eventually claims the life of his girlfriend. Male violence, and its victims, are also the central theme of Zephaniah’s 2007 novel Teacher’s Dead. The novel explores the difficult topic of a teacher being killed, a narrative told through the eyes of a sensitive 15 year old boy, Jackson Jones.

Like Gangsta Rap, Teacher’s Dead offers an anatomy of violence for today’s youth, revealing its complex causes in ways that trouble the boundaries between criminals and victims. More broadly though, and what characterises all of Zephaniah’s writing to date, is its stress on the redemptive forces of love, laughter, and peace.

Dr James Procter, 2010