Biography

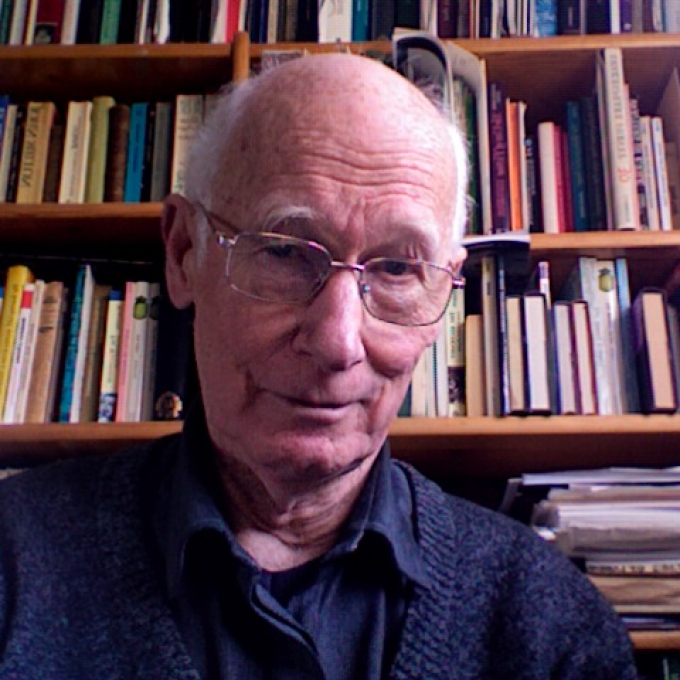

Professor Andrew (John) Gurr was born on 23 December 1936 in Leicester. He grew up in New Zealand and was educated at the University of Auckland and Cambridge University.

His academic posts include lectureships in English at Victoria University of Wellington (1959), the University of Leeds (1962-9) and the University of Nairobi (1969-73), where he was also Head of Department. From 1976 until his retirement in 2002 he was professor of English at the University of Reading (Head of Department, 1979-86), where he taught Shakespeare studies and where he is now Emeritus Professor.

An acclaimed Shakespearean scholar, Professor Gurr's published work on the Shakespearean theatre includes The Shakespearean Stage, 1574-1642 (1970), Playgoing in Shakespeare's London (1987), The Shakespearean Playing Companies (1996) and Staging in Shakespeare's Theatres (2000). He has also written a biography of Shakespeare (1996), and, as chief academic advisor, was a key figure in the project to rebuild Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in London. He was Director of Globe Research for twenty years.

Professor Gurr has also edited several of Shakespeare's plays, including Richard II (1984) and Henry V (1992), and The First Quarto of Henry V (2000), as well as editor of three plays by Beaumont and Fletcher, two books on African literature: Black Aesthetics (with Pio Zimiru, 1973) and Writers in East Africa (with Angus Calder, 1974); and is author of a critical study (with Claire Hanson) of Katherine Mansfield (1981).

His latest book is Shakespeare's Opposites: The Admiral's Company 1594 - 1625 (2009).

He is a member of the Association of Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies. He was editor of the Modern Language Review between 1988 and 1998 and was editor of the Yearbook of English Studies. He also regularly contributes articles on Shakespeare to publications ranging from the Shakespeare Survey to the Times Literary Supplement.

Professor Gurr lives in Reading.

Critical perspective

While he has been retired for several years now, Andrew Gurr remains a refreshing, if unlikely mix of path-breaking Renaissance scholar and pioneering postcolonial critic.

He is a man who is as much at home with Katherine Mansfield as he is with Macbeth, and it is a testament to his continued relevance and resonance within the academy that many of his books have gone through numerous editions.

In terms of what was known at the time as Commonwealth literature, Gurr had a particular interest in East African writing, as well as in canonical postcolonial writers such as V.S. Naipaul and Ngugi wa Thiongo. He was also interested in modernist writers such as James Joyce and Katherine Mansfield, who had complex relations with colonial culture. In Katherine Mansfield (1981) Gurr, together with his co-author Claire Hanson, locates the New Zealand born writer within the context of the modern short story, focusing upon her stylistic use of plotless narrative, symbolism and epiphany. Meanwhile, in Writers in Exile: the Identity of Home in Modern Literature (1981) Gurr looks more generally at the work of Mansfield alongside other modern writers (including Joyce, Naipaul, and Ngugi) in terms of questions of modernity, home and homelessness. While such connections are today fashionable, Gurr deserves to be recognised as one of the first to think through some of the key correspondences between modernism, empire and postcolonialism.

Nevertheless, it is for his contributions to Shakespeare studies and Renaissance drama that Andrew Gurr is, rightly, best known. Gurr has edited a number of Shakespeare’s plays including King Richard II (1992), and King Henry V (1992), but he is best known for his prolonged investigations, across a series of different books, into the immediate physical and social contexts surrounding the plays and their contemporary performances, from audiences, to stages to theatre companies. As Gurr himself once put it:

'Modern playgoers think about theatre as a two dimensional experience, like cinema. Personally I am rather hostile to Shakespeare on film, because it puts audiences back in the dark, where they are looking at the picture instead of sharing the experiences. For Shakespeare however, theatre was three dimensional and people came to hear a play, not to see it. The design of the early theatres in which the plays of Shakespeare’s time were staged shows us how the audience was supposed to encircle the stage – ideal for listening but not for seeing.'

In The Shakespearean Stage, 1574-1642 (1970), now in its fourth edition, Gurr provides the first authoritative, and comprehensive account of the original staging practices, theatres and acting companies associated with Shakespeare’s drama. Quickly establishing itself as a classic among undergraduates and interested readers, the book was praised in Shakespeare Quarterly for the 'admirable … way it condenses a great deal of technical information into a readable and judicious account. Gurr writes graciously, has a gift for piquant illustration, and provides us with generous quotations from essential documents …'.

Gurr’s interest in the hitherto neglected physical world that surrounded Shakespeare’s plays is pursued further in Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London (1987). Like a literary detective, Gurr pieces together fragments of information to provide a compelling picture of Renaissance drama in action. Gurr’s strengths lie in what we might term a sort of peripheral vision, which allows him to recreate the world surrounding the drama, from auditorium behaviour, to the class composition of audiences, to questions of taste, and even an investigation of the psychological make up of the spectator. It is a topic which gives a new twist in Staging in Shakespeare’s Theatres (2000), an introductory text focusing on the gestures, props and costumes of the Shakesperean stage. The book is written with Gurr’s typical forensic attention to detail: no less than three chapters are dedicated to the process of players exiting and entering the stage. Thus, with characteristic ease, he puts flesh on the bones of Shakespeare’s plays and the original contexts of their reception:

'For Elizabethans the opening of a play was a public event, and an act of choice which had an almost religious dimension. Up to three thousand people paid to have themselves shut into a large wooden-framed auditorium, expecting to spend two or three hours of their afternoon enjoying a game or play or illusion. They came to watch a fiction, the acting out of a story which they would witness, well aware of the novelty and the religious doubts about the choice they made in observing an act designed explicitly to deceive them, willing to suspend their disbelief while they sat or stood in varying kinds of discomfort.'

There is a deceptively simple drama about these lines, which recreate the Shakespearean audience through an almost intuitive narrative that captures the reader with its apparent spontaneity. But Gurr’s intuitions are based on painstaking research of the archives and are far from mere suppositions.

Gurr’s most recent books, The Shakespeare Company (2004) and Shakespeare’s Opposites: The Admiral's Company 1594-1625 (2009), are closely connected. The former provides an exhaustive history of the Shakespeare Company, an established team of players for 48 years (1594 to 1642). With typical rigour, Gurr attends roundly, and for the first time, to every dimension of the company, from the central part played by Shakespeare himself, to more mundane issues of finance and management. Meanwhile, in Shakespeare’s Opposites, Gurr focuses on the Admiral’s Men, the acting company which (along with the Shakespeare Company) performed to Londoners during the late sixteenth century.

Gurr remains an active speaker on the national and global circuit, a popular and public intellectual who retains a fitting (given his life long preoccupation with the bard’s reception) commitment to his audience.

Dr James Procter, 2009