- ©

- Mark Pringle

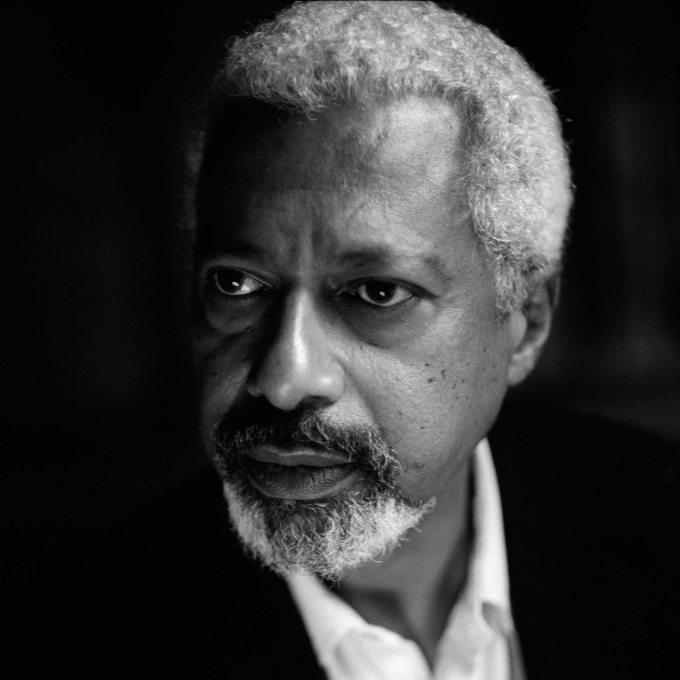

Abdulrazak Gurnah

- Zanzibar

Biography

Novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah was born in 1948 on the island of Zanzibar off the coast of East Africa. He came to Britain as a student in 1968. He is on the advisory board of the journal Wasafiri and lives in Canterbury, after retiring as a professor of English at the University of Kent.

His first three novels, Memory of Departure (1987), Pilgrims Way (1988) and Dottie (1990), document the immigrant experience in contemporary Britain from different perspectives. His fourth novel, Paradise (1994), is set in colonial East Africa during the First World War and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction. Admiring Silence (1996) tells the story of a young man who leaves Zanzibar and emigrates to England where he marries and becomes a teacher. A return visit to his native country 20 years later profoundly affects his attitude towards both himself and his marriage. By the Sea (2001) is narrated by Saleh Omar, an elderly asylum-seeker living in an English seaside town.

His latest novels are Desertion (2005), shortlisted for a 2006 Commonwealth Writers Prize, The Last Gift (2011), Gravel Heart (2017), and Afterlives (2020). In 2007 he edited The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie.

He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2006, and in 2021 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Critical perspective

The writings of Abdulrazak Gurnah are dominated, both in form and content, by the issues of identity, memory and displacement, and how these are shaped by the legacies of colonialism which the author effectively describes as “the great machinery of conquest and empire”. Far from being mere thematic concerns, these issues permeate Gurnah’s style of storytelling, especially in his later fiction, where narration becomes increasingly nonlinear and willfully retains important details from the reader, revealing them as the characters’ memory comes to terms with the burdens of the past. Gurnah’s novels interrogate the ways in which writing can embody shocking memories, where the personal level always encounters the larger traumas of past and present history, such as colonialism, the two World Wars, the Bosnian War of the 1990s and September 11th. The main storyline often breaks down into multiple narrative threads. The words of the narrator of Desertion (2005) define the fictional labyrinth through which both readers and characters move: “It is about how one story contains many and how they belong not to us but are part of the random currents of our time, and about how stories capture us and entangle us for all time.”

Gurnah creates fictional characters who are constantly negotiating past and present in the construction of new identities to fit their new environments. Their narratives are all premised on the shattering impact that migration to a new geographical and social context has for the character’s identities. In The Last Gift (2011), Abbas, the central character, narrates exotic stories to his children from his past as a merchant sailor to avoid telling them his “real” immigrant story, painful and haunting: “those deep silent places that he could not help returning to, that he hated returning to”. The gift of the title, then, could be the new awareness of the importance of rootedness and cultural heritage that both Abbas and his wife Maryam bequeath to their children, after having themselves shunned it for so long. Yet, even this new awareness is undercut by irony, in line with the rejection of fixed identities that characterizes so much of Gurnah’s fiction: at the end of the novel, Abbas’s son Jamal declares that he is writing “another father story. Such a predictable immigrant subject”. In the same way, his sister Hanna wonders whether they will ever go to Zanzibar or whether the island will remain “a nice story, a pleasing possibility, a happy myth”. Much in the same vein, Rashid, the narrator of Desertion (2005), fears “repeating the cliché of the miraculous” that characterizes Orientalist representations of the East. There is a constant self-consciousness about Gurnah’s prose that undermines the pleas for authenticity that it sometimes brings forward. In addition, reading and writing are often hailed as means of emancipation for the oppressed and, as such, contrasted by colonial and patriarchal authorities or used as pawns for sexual and psychological submission, as for the characters of Hamza and Afiya in Afterlives.

To Gurnah, who, like his characters, experienced displacement from his native Zanzibar and migration to Britain when he was 17, identity is a matter of constant change. Besides forging new identities for themselves, Gurnah’s main characters unsettle the identities of the European people they encounter in the environments to where they migrate. As cultural critic Paul Gilroy has pointed out in his seminal study Between Camps (2000), the projection of pure national and ethnic identities is threatened by “the ever-present possibility of contamination” brought about by migratory processes. The protagonists of Gurnah’s novels represent this contamination of other people’s identities through their difference. When the unnamed narrator of Admiring Silence (1996) meets the parents of his girlfriend to tell them she is pregnant, they look at him with hatred because now their daughter “would have to live with a kind of contamination for the rest of her life. She would not be able to be a normal English woman again, leading an uncomplicated English life among English people.” In The Last Gift, Hanna’s visit to his fiancé’s family results in their disappointment as she refuses to comply with their expectations of providing “a little biographical sketch of distant but not unfamiliar origins” and in her stubborn identification with Britishness although her father comes from East Africa. In Afterlives (2020), which reconstructs the years of German colonial rule in East Africa leading up to the First World War, the characters of Ilyas and Hamza represent a reverse process of contamination: they become Schutztruppe Askaris, thus contaminated by German colonial cruelty, which they will perpetrate against their fellow Africans.

Migration and displacement, whether from East Africa to Europe or within Africa itself, and the clash of cultures they engineer, are central to all Gurnah’s novels. Memory of Departure (1987) analyses the protagonist’s reasons behind his decision to leave his small African coastal village, while The Last Gift reconstructs both Abbas’s painful memories of his childhood in Zanzibar with his decision to become uprooted and his wife Maryam’s quest for a foster family in Britain. Pilgrim’s Way (1988) portrays the struggle of a Muslim student from Tanzania against the provincial and racist culture of the small English town to where he has migrated. Paradise (1994), which was shortlisted for the 1994 Booker Prize for Fiction, retains instead an African setting. It explores Yusuf’s journey from his parents’ poor house to the wealthy mansion of Uncle Aziz to whom he has been pawned to pay his father’s debts, a condition of enslavement within one’s own family that resembles Afiya’s in Afterlives or Abbas’s in The Last Gift. The anonymous narrator of Admiring Silence has built a new life for himself in Britain, escaping from the state terror reigning in his native Zanzibar. He has fashioned romantic stories of his homeland for his wife and her parents, which are shattered when he has to return to Africa. In By the Sea (2001), Saleh Omar, an unusually old asylum-seeker who has just arrived in Britain, and Latif Mahmud, a university lecturer who has been in England for several decades, meet to uncover stories from their past which will reveal to each other unexpected connections. In Desertion, the encounter between the English Orientalist Martin Pearce and Hassanali, a shopkeeper from a small coastal town in Kenya, at the turn of the nineteenth century provokes the contamination of colonizers and colonized in the backdrop of the vanishing British Empire.

To Gurnah, migration is not merely an autobiographical experience but “one of the stories of our times”, and a representative one at that. The longing for the people and places left behind “intensifies recollection, which is the writer’s hinterland' (Writing and Place). Gurnah’s narrators share this rejection of a mere autobiographical relevance to their narratives. Rashid in Desertion clearly argues that “there is, as you can see, an I in this story, but it is not a story about me. It is one about all of us”. In general, Gurnah’s characters look back upon their pasts with mixed feelings of bitterness and guilt for what they have left behind. Often, movement to a different place entails the attempt to erase all contact with past families which, however, still haunt the character’s minds. Particularly Gurnah’s male characters are tormented by the desertion of their original family. To Yusuf, the protagonist of Paradise, “images of his abandonment came to him in a spate”. Since his arrival in Britain through East Germany, Latif Mahmud has never sought contact with his family left behind in Zanzibar but finds that his past, though distant, still looms large over him and influences his present. Tellingly, he compares memory to “a dour place … a dim gutted warehouse with rotting planks and rusted ladders” (By the Sea). In The Last Gift, Abbas works through his sense of guilt throughout the narrative which finally becomes his own as it takes the form of a first person narration in the last chapter ‘Rites’: “I remember many things and I remember every day, however hard I try to forget.”

Gurnah’s novels and critical essays are meditations on the unsettling power of hybridity and of the challenges it brings to racial assumptions fostered by the enduring presence of a colonialist outlook. Gurnah’s project is to question these assumptions and to re-inscribe into History the perspectives of the colonized, thus decentering the points of view that usually inform our social, political and cultural understanding of the past. The First World War in Afterlives, for example, is narrated through Hamza, an African recruit in the German Army. Through his eyes, we read of a different kind of war: usually considered “a sideshow to the great tragedies in Europe”, the African front meant for those who lived through it “that their land was soaked in blood and littered with corpses”. In Desertion, the “first sighting” of the Orientalist Pearce is told in terms of mystery and ‘othering’ usually employed in colonialist narratives to describe the natives. Gurnah thus prompts a reversal of the hegemonic narratives that conceive Western citizens “as the normative, free from culture or ethnicity, free from difference” (Writing and Place) and immigrants as “hysterical strangers squatting dangerously inside the gates” (Admiring Silence). Therefore, his writings are particularly relevant to our present era, when the meaning of the colonial past is further disputed as millions of people from those former colonies reclaim their citizenship rights in a global world.

CRITICAL PERSPECTIVE by LUCA PRONO (2021)