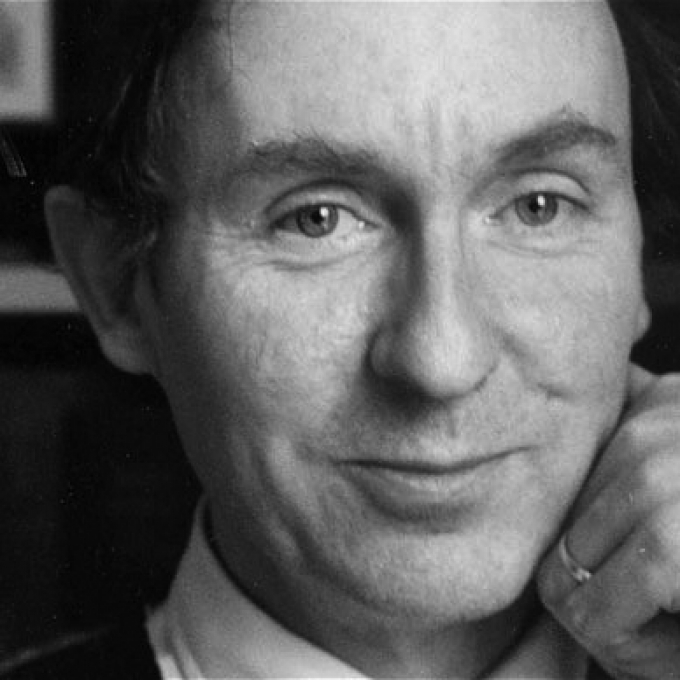

A.N. Wilson

- Stafford, England

Biography

Andrew Norman Wilson was born in Staffordshire in 1950 and is best known as a biographer, novelist, journalist and essayist.

Wilson was educated at Rugby School and later attended New College, Oxford (B.A., 1972; M.A., 1976). Initially drawn to the teaching profession and priesthood, Wilson settled upon a life of writing, and published his first novel, The Sweets of Pimlico in 1977. He has since published over 40 works of fiction and non-fiction.

He is a regular voice on BBC radio, and an occasional columnist for the Daily Mail, Telegraph, London Evening Standard, Financial Times, the Times Literary Supplement, New Statesman, The Spectator and The Observer. A selection of Wilson’s journalism can be found in his collection Pen Friends from Porlock (1989)

A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and an award-winning biographer and a celebrated novelist, Wilson holds a prominent position in the world of literature and journalism.

Critical perspective

Journalism, biography, history, and fiction: A.N. Wilson’s writing often combines the characteristics and qualities associated with all four of his preferred genres.

His biographies and historical studies are animated by the eye of a novelist in that they tend to be plotted around anecdotes, coincidences, and creative connections that eschew, or otherwise subordinate, dates and strict historical chronology in favour of ‘story’.

Conversely, his fiction is frequently inspired by particular periods and historical figures (e.g. Winnie and Wolf (2007)), or are themselves historical novels (e.g. The Potter’s Hand (2012)), or novels of ideas (e.g. My Name is Legion (2004)). Even Wilson’s critics concede he has a knack for ‘good copy’ that extends beyond the shorter journalism, and Wilson has proved himself capable of catching and holding his readers’ attention across diverse epic narratives, from The Elizabethans (2011) to The Victorians (2002), the latter stretching to 738 pages.

While Wilson’s writing tends to be perennially popular among general audiences, Wilson-the-man has generated more polarized opinion. Outspoken, waspish and often conservative in his views (see, for instance, his comments on immigration, terrorism, history teaching, and political correctness), he is sometimes labelled in the broadsheets a ‘young fogie’. Wilson’s writing is by turns provocative, opinionated, and reactionary. His acerbic style has landed him in hot water on more than one occasion, and he has had to handle the threat of libel action as well as a hoax from an anonymous enemy. The latter concerned a letter that came into Wilson’s possession while he was researching his Betjeman (2006) biography, and which he decided to reproduce in the volume, only to discover after publication that it was false.

The hoax letter seemed to highlight a certain lack of scholarly rigor or discrimination in Betjeman, and academics and area specialists have been quick to point out local flaws elsewhere in Wilson’s non-fiction (the outdated critical sources in his biography of Hitler; the suggestion that fourteen was the age of marriage in Elizabethan England in The Elizabethans; the apparent confusion around the details of the hanging of Derek Bentley in Our Times; quibbles over Wilson’s conception of C.S. Lewis in C.S. Lewis (2005)). Wilson himself remains philosophical on this emphasis on what he calls his ‘howlers’: ‘Dons sometimes do that to generalists’. Anyway, such comments arguably miss the true contribution of Wilson’s non-fiction, which hinges less on specialist detail and inside knowledge than on the ability to communicate history across periods with both immediacy and complexity.

The Victorians is perhaps Wilson’s most outstanding achievement in this respect. Crowded, monumental and panoramic, it is a book that avoids retreating into easy abstractions, or becoming overly fixated on facts, by staying close to the lives of people, both famous and anonymous. Decade by decade, in a trademark tone that is gossipy and intimate, Wilson animates for his readers the lives of Darwin, Marx, Kipling and Disraeli (among countless others), suggesting how many of their preoccupations and concerns are also ours in the present. Wilson’s sequel, After the Victorians is framed by the fifty years that separate the death of Victoria in 1901 and the Queen’s Coronation in 1953. Our Times, which covers the second half of the twentieth century, complete the trilogy.

However, while Wilson’s non-fiction stretches from the medieval period (see Dante in Love (2011)) to the present, it is the nineteenth century that has proved to be Wilson’s most successful stomping ground to date. His account of the great Russian novelist, Tolstoy, was described in The Economist as ‘among the most impressively intelligent biographies ever written’. Tolstoy: a biography (1998, re-issued 2012) works so well because it does not force the literary works to conform to a genetic imprint of the author. Rather Wilson considers Tolstoy’s work as the product of his wider encounters with women, Russia and religion.

Religion is an ongoing, even insistent subject in Wilson’s work. Having trained for the priesthood after University, he renounced his faith in the late 1980s only to return to the fold some twenty years later. It seems no coincidence that the periods and people who interest him most are centrally concerned with faith, or faithlessness. Wilson has penned ‘biographies’ of Jesus Christ and St Paul, as well as a pamphlet Against Religion (1992) in which, as the blurb has it: ‘the author argues that religion has inspired many of man's worst evils: war, prejudice, bigotry, cruelty, race hatred and fear. Without it, man would be free to be God.’

Religion is also a thematic preoccupation of Wilson’s fiction, from Who Was Oswald Fish? (1981) to The Vicar of Sorrows (1993), and My Name Is Legion (2004). Satire and comedy are the characteristic planks of these, and many other Wilson novels, but as with biography, he is no one trick pony when it comes to fiction. A Jealous Ghost (2006) is a chilling contemporary reworking of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. His most recent work, The Potter’s Hand (2012) is a critically acclaimed historical fiction centred on Josiah Wedgwood, the renowned eighteenth century industrialist and ceramics pioneer. When Wedgwood is commissioned to produce a 1000-piece dinner service for Catherine the Great, The Potter’s Hand develops into a novel about political history as much as pottery. An epic tale that places Wedgwood and his dynasty within the wider contexts of the slave trade, and the American and French Revolutions, the novel was described in the Guardian as ‘erudite’, ‘engaging and elegantly written’.