Biography

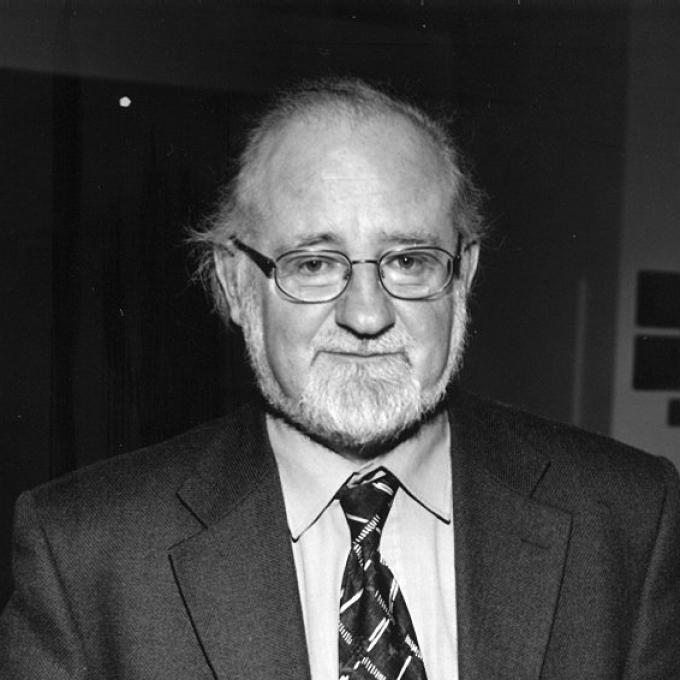

John F. Deane was born on Achill Island in 1943. He is the author of several poetry collections and also writes short stories and novels. He has translated several books of poetry from French, Romanian and Swedish.

His poetry collections include Toccata and Fugue (2001); Manhandling the Deity (2003), shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize; A Little Book of Hours (2008); The Eye of the Hare (2011); and Snow Falling on Chestnut Hill: New & Selected

Poems (2012). His poetry has been translated into various languages and his poems in Italian, translated by Robert Cogo, won the 2002 Premio Internazionale di Poesia Citta de Marinea for best foreign poetry of the year. He has also translated the work of other poets, including Marin Sorescu's The Youth of Don Quixote in 1987; Tomas Transtromer's The Wild Marketplace in 1985, and For the Living and the Dead, in 1994; and Jacques Rancourt's The Distribution of Bodies in 1995.

His books of fiction include the recent short story collection, The Heather Fields and other stories (2007), and the novels Undertow (2002) and Where No Storms Come (2010). He is also the author of three collections of essays about religious poetry: In Dogged Loyalty (2006); From the Marrow Bone (2008); and The Works of Love (2010).

John F. Deane is the founder of Dedalus Press, and was editor there until 2004. He also founded Poetry Ireland and Poetry Ireland Review in 1979. He was elected Secretary-General of the European Academy of Poetry in 1996 and President in 2008. In April 2012, John F. Deane was Distinguished Visiting Professor in Suffolk University, Boston, USA. He is a member of Aosdána, and lives in Dublin.

In 2015 his memoir Give Dust a Tongue was published by Columba Press Dublin and a new collection of poetry Semibreve was published by Carcanet Press.

Critical perspective

Though associated more with poetry than with fiction – partly, no doubt, because of his prolific work as a poetry editor and publisher in his native Ireland – John F.Deane is an accomplished and wholly original writer of novels and short stories.

Consider this disorienting, grim, shockingly vivid passage from ‘The Photograph’ (The Heather Fields and other stories, 2007):

‘There was a man in the hallway, on his knees on the rust-flagged floor, his left hand raised to the wall for support, his right hand clutching his throat. […] He was gasping for breath, trying to drag himself along towards the end of the hallway, towards the only door that seemed perfectly intact in the house. He was making strange, half-strangled sounds and it was very clear that he was in a terminal state, and suffering greatly. I did not know what to do. The man was vaguely familiar to me and yet I knew an overpowering dread of him; some ill-defined sense of terror held me fixed to where I stood, useless, helpless.’

No two of Deane’s works of fiction are particularly alike, but many of them share a dream-like quality, a flirtation with the dark possibilities of magical realism, incisive and questioning analyses of our ponderous human responses to difficulty, fear, normalcy, indecision.

In the poems, Deane shows the same talent for terse, precise explorations of unsettled emotion. In ‘Winter in Meath’, from the collection also called Winter in Meath (1984), we read:

‘This is a terrible desolation –

the word "forever" stilling all the air

to glass.’

Those last two words, falling beyond the enjambment and the stanza to which they might otherwise belong (for these are the last two words of this section of the poem) and not needed to lend the two lines above any grammatical correctness; they jolt utterly, and with finality, the emotions of the poem.

Deane has a deeply-felt Christian – or, more accurately, culturally Christian – conscience. But God is not always a particularly consoling presence. In ‘The Fox-God’ from Christ, with Urban Fox (1997), He is, if anything, a bitterly-felt absence. A fox has been snared and dies in its trap:

‘The fox, they will say, is vermin, and its god

a vermin god; it will not know, poor creature,

how it is suffering – it is yourself you grieve for.

While I, being still a lover of angels, demanding

a Jacob’s ladder beyond our fields, breathed

may El Shaddai console you

into that darkness.

I know there was no consolation. No fox-god came.’

But there is little between us and the fox, ultimately. Indeed, the fox is blessed, if anything, because humans certainly understand how they will suffer:

‘The gap out of life, we have learned,

is fenced over with affliction. We, too, some dusk,

will take a stone for pillow, we will lie down, snared,

on the uncaring earth. Poor creatures. Poor creatures.’

In ‘Under the Same Sky’, from Toccata and Fugue (2000), man is shown to be far less worthy of divine attention – and less comfortable in his life – than the animals. Rats and fowl variously do their things,

‘… and only the man-shape,

irritable in the tree’s shelter, stands alien,

judgemental, in need of redemption.’

Presumably this man hiding in the undergrowth is a hunter or a fisherman: he is, in one sense, in control of what he surveys. But he is also an impostor, does not belong there, and is cursed by his own understanding of what is to come – unlike the animals in front of him.

There is a pervading sense in Deane’s work of the fragility, and preciousness, of human life. In ‘Heatherfield’ (Christ, with Urban Fox) ‘the elderly / gather in small surviving groups’ and ‘clap their hands repeatedly / to applaud their living still’, which seems rather pathetic and futile but what else can they do? In ‘The Child’, from Toccata and Fugue, the child in question pours salt on one snail so that it ‘slobbering, dissolved into a mess’, and kicks another into the road where it is subsequently run over:

‘and what was it entered him then? that he, too,

partakes of the essence of matter,

inertia, fragility, impotence,

he, too, attending on the footpath’s edge.’

The use of definite article in the title and the repetition of ‘he, too’ serve to imply that the child in question stands for all children and therefore for all of us, too.

Deane is one of Ireland’s finest landscape and nature poets, not least because he so considerately fuses acute observations of the physical world with the hurt and fear of sentient beings. Consider the mournful alliteration of ‘To Market, To Market’ (A Little Book of Hours, 2008), their cadenced lines imbued with an almost Anglo-Saxon stateliness and solemnity:

‘The day was drawky, with a drawling mist

coming chill across the marshlands;

the church of Ireland stood, damp and dumpy,

crows squabbling on its crenulated stump; cattle,

that had summered in a clover field, have been herded

through plosh and muck into a lorry, have dropped

their dung of terror on slat and road.’

There is an inevitability about all of this, a sense in which its gruesomeness is too normal to register as gruesome, the cadenced and measured prosody and complex sentence structure giving the scene an inexorable feel – and all of this is achieved with the use of such lush, beautiful language.

Deane remains one of our finest writers when it comes to exploring the unresolvable existential flux of the human condition, the role of religion in modern life, and what can happen when the two do not seem compatible. His recent novel, Where No Storms Come (Blackstaff, 2010), is perhaps his most searching exploration of these themes to date, following as it does the friendship between a man and a woman, respectively destined for life in the priesthood and the convent. In this work Deane continues to ask hard moral and philosophical questions with the skill and insight to deal competently and movingly with a dearth of solid answers.

Rory Waterman, 2010

Bibliography

Awards

Author statement

I write poetry and fiction to help me recover what I have lost, through personal experience, and through doubt and hesitations because of contemporary philosophies and events, in the area of faith; my work is to re-locate, to re-name and to re-evaluate the Christian experience and values, not tied to any individual church or churches. I write to set the Christ-life echoing.