Text Me When You Get Home: the Evolution and Triumph of Modern Female Friendship by Kayleen Schaefer

It’s a non-fiction book about the change in perspective around female friendship over the last few years, featuring interviews with a huge range of people including Judy Blume. The book looks at the radical potential of female friendships, how women support one another in a way that runs counter to the often one-dimensional representations of these friendships in the media.

The bit I’ve found most interesting so far is an examination of how the idea that ‘girls are mean’ became mainstream. Many of Schaefer’s interviewees point out that if you tell a group repeatedly that they are a certain way, it becomes self-fulfilling, whether it has any basis in fact originally or not.

It’s a very interesting book which sparks lots of thoughts and further discussions.

Harriet Williams, Literatutre Programme Manager

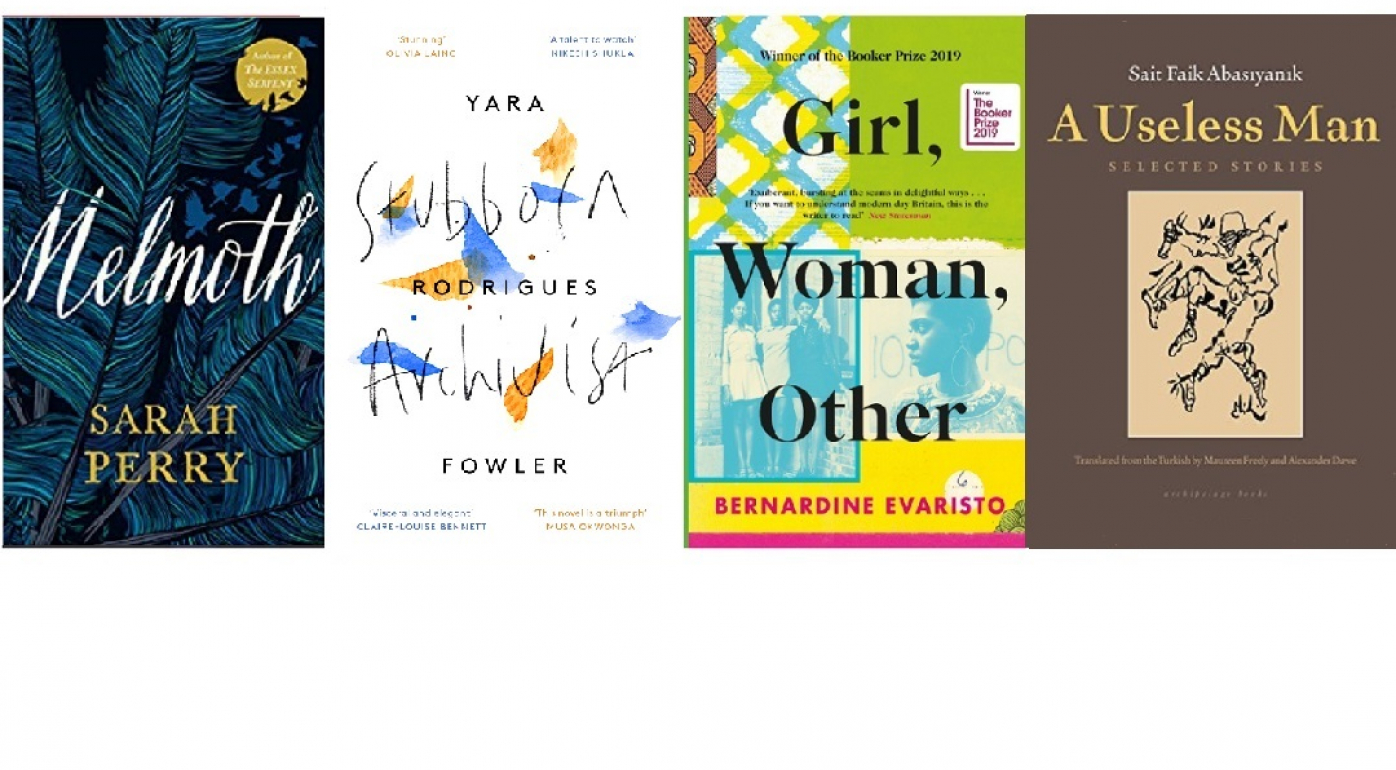

The Stubborn Archivist by Yara Rodriques Fowler

This month I’ve been reading The Stubborn Archivist, by Yara Rodrigues Fowler which was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writers Award. It’s a really sophisticated debut novel set in London and Brazil, exploring the intricacies of the relationship between the narrator who is a ‘third-culture’ half British half Brazilian young woman, her family, and their histories. The author plays with form in such a way that connects fragments of memories together or makes them jar against each other revealing trauma that lives across the generations. She is definitely someone to watch!

Rachel Stevens, Director Literature

Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo

Following a sneak preview of this book at our gender and sexuality Literature Seminar in Germany in January 2018 when Bernardine read us a short extract, I have belatedly read this magnificent book in its entirety. The book is narrated by 12 different, interconnected characters, the majority of them Black British women, within historical and contemporary settings, and does much to give central stage to voices previously denied a platform in mainstream society. Written in a flowing, pacey style, without full stops and with very limited punctuation, this book is an important one in terms of style and content. A worthy co-winner of the Booker Prize.

Sinead Russel, Director Literature

Sait Faik Abasıyanık – A Useless Man: Selected Stories (trans. Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe)

It’s an indication of the strength of the translations that I feel so bad I can’t read these in the original Turkish. The limpid way that Sait Faik writes goes along well with the feel he has for the numinousness of ordinary life, and reminds me a bit of John Berger’s 'Into Their Labours' trilogy, or Chekhov. He is also a very discrete writer: the stories in this book tend to only a few pages, hinging on little telling details/objects like a silk handkerchief or a steaming samovar. I think this is the only selection of Sait Faik’s work available in English, though I might be wrong; I bought it at his house which is now a museum, on Burgazada.

Joe White, Literature Coordinator

Melmoth by Sarah Perry

In the Gospel According to Luke, a group of women accompany Mary Magdalene to the tomb of Jesus, where they see that the stone has been rolled away and Christ has risen. When they return to tell others what they have witnessed, however, "these words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them."

In Sarah Perry's Melmoth, one woman among them, knowing she wouldn't be believed, lied, denying the truth of the resurrection. She is now Melmoth the Witness, cursed to wander the world forever, finding subsequent witnesses to humankind's many atrocities, and offering them a gothic form of company – one that is alluring, repellent, and comforting all at once.

I've not read Charles Maturin's original Melmoth the Wanderer (which Perry absorbs into her novel, making it a fictional reworking of the “real” Melmoth) but if it's half as good as Perry's remarkable novel, I probably should. Melmoth manages to be completely serious in its ethical viewpoint, precise in its evocations of personal pain and political terror, and still full of humour and postmodern joy. There are stories within stories, pitch-perfect historical pastiches, a direct-to-reader address from the narrative voice, and cloudfuls of jackdaws descending upon Prague. Somehow, it does all this without making light of the real atrocities it describes, and without detracting from its argument of what we can do, as witnesses, to counter the terrible acts we see in society.

Swithun Cooper, Literature Research Manager