Humour, or travel? It sounds unlikely now, but when Caitlin Moran first published How to Be a Woman, these were the two areas of the bookshop that sellers were torn between placing it. Moran’s feminist memoir-polemic was considered an outsider at the time; it went on to sell over one million copies, inspire responses and imitations (the latest of which is Robert Webb’s How Not to Be a Boy) and prove to publishers that the public were hungry for personal, political writing – books in which an author explores her life through the issues that shaped and shaded it.

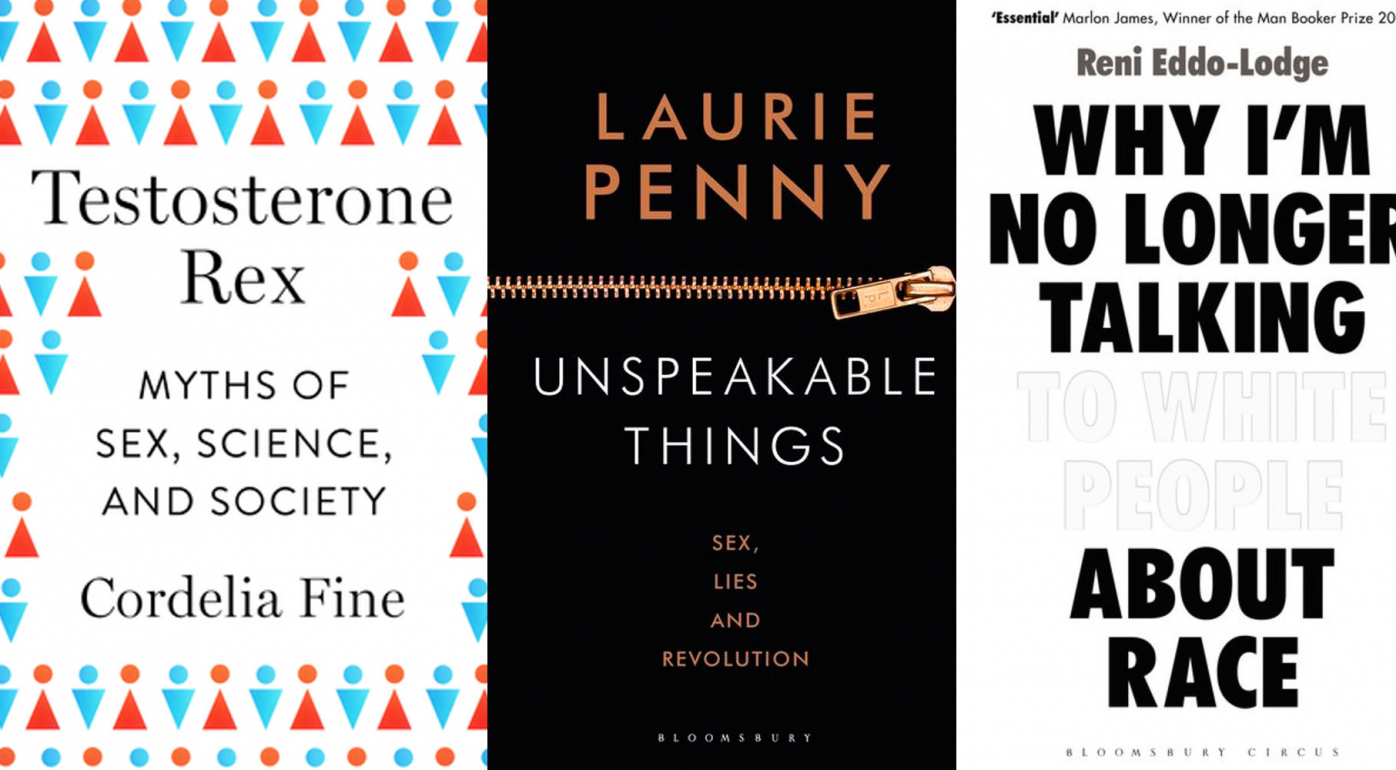

A new generation of political non-fiction writers has since found fame. Many, of course, were writing long before: Laurie Penny began blogging independently in 2007 and was soon publishing with indie presses Zero Books and Pluto Press. In 2014 Bloomsbury brought out Unspeakable Things, in which she uses incidents in her adolescence and early adulthood to discuss the effects of gender inequality under capitalism; a collection of essays, Bitch Doctrine, has just appeared. Penny’s feminist worldview is different to Moran’s – taking in polyamory, the gender binary and blame culture – and Bitch Doctrine is particularly engaging when it explores intersectionality, such as her piece on the 2016 US election, which highlights how western feminism is tangled up with class privilege and race. Often witty and always accessible, Bitch Doctrine expresses complex ideas succinctly, making them less daunting to readers who will discover (or will have already discovered) similar arguments in the work of Charlotte Cooper, whose Fat Activism discusses the political nature of fat female bodies, and Afua Hirsch, whose forthcoming Brit(ish) explores everyday racism as Laura Bates took on Everyday Sexism in 2014.

Intersectional feminism, too, holds an important place in Reni Eddo-Lodge's Why I'm No Longer Talking to White People About Race. Recently longlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize, the book begins with personal reflection, but is mostly structured around the past, present and future of race and racism in Britain. Eddo-Lodge’s work as a journalist means she is brilliant at presenting the facts and findings that illustrate her points and propel her arguments forward – when discussing the slave trade, she references documents that refer to black people as “cattle”, and her chapter on systemic racism quotes from essays written by (white) police cadets on a training course (“they come over here from tin-pot-banana countries…They are, by nature unintelegent [sic]”). She then uses incidents from her own life, and those of her peers, to portray the human effects of her evidence – the emotional as well as statistical impacts of racism. When, at a feminist conference, she sees a sign-up sheet for a black women’s group has been vandalised, the reader feels the sting of it too, and asks why the vandal felt justified in doing it. Eddo-Lodge does not comment on it: she allows the information to speak for itself.

Another non-fiction writer appearing on prize shortlists lately is Cordelia Fine, the author of Testosterone Rex. The book sees Fine challenging the conventions of masculinity and femininity that dominate gender debates, and dissecting the scientific research that props them up. She opens by describing how we tend to think that men are genetically predisposed to being “risk-taking and competitive” because the ones who passed on their genes were successful and daring hunter-gatherers, while the “ancestral women” who survived were “psychologically inclined to play a safer game”. She then quotes a psychologist at the University of Glasgow who states that these separate skills explain the gender pay gap.

Fine swiftly takes these assumptions to pieces (and makes short work of whether scientists in Glasgow write their psychology papers in the style of hunter-gatherers). Using a huge variety of sources, from neuroscience journals to dating manuals, she shows how the “facts” of testosterone have been used to scapegoat and justify, to avoid social change, and to duck out of new ways of thinking; she then lays out a possible future waiting for us once we break this pattern. As she says in her introduction: “It’s time to say good-bye, and move on.”

This idea of “moving on” is present in each of these works: Penny ends Bitch Doctrine with an image of a future to fight for, while Eddo-Lodge’s book invites her readers to listen, reconsider, and work for something new. When reading these books, sometimes our own lives are explained, and we see the issues we have encountered but have never found the words for ourselves; sometimes we identify with others, spending time with their troubles and understanding their anger. A recent Reading Agency report claimed that reading fiction improves our empathy and communication skills – and if we can combine these skills with the facts and political awareness offered in non-fiction, by writers like these, we are well equipped to use literature to discuss the mistakes of the past and the problems of the present, and to ask how to use it to build a better future.